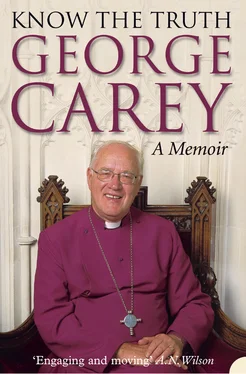

George Carey - Know the Truth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «George Carey - Know the Truth» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Know the Truth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Know the Truth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Know the Truth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Know the Truth — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Know the Truth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I decided to get my Bishop’s advice. I did not know the Bishop of Durham, John Habgood, very well, though I had met him many times. He was an excellent speaker, preacher and scholar, but seemed rather remote to ordinary mortals. He had no capacity for small-talk, and most clergy in the diocese dismissed him as a pastor. This latter estimate, I knew first-hand, was mistaken. Two years before I had had a car crash and had ended up in hospital, following which I had required several weeks’ convalescence. On hearing this, John Habgood made available a sum of money to allow me to have a proper rest. I knew that, in spite of the impression he could give at times, he was a caring man, and would answer every question with great insight. I outlined my predicament to him, and without hesitation he gave his opinion that Trinity needed to be brought into the Church of England, and that I was ideally positioned to do it. He urged me to be positive about meeting the College Council, but said that I must make it clear to them that I had to finish the building project at St Nic’s before I could possibly take up the position.

In the light of that advice I accepted the invitation to visit the college and meet the Council. To my surprise, I found that it was set up as a formal interview. As I was not convinced I should even be considering the post, I had not prepared myself to argue my corner. Before the interview I met Trevor Lloyd, later Archdeacon of Barnstaple, the other person being interviewed that day, who shared with me his opinion that Trinity was at a crossroads – unpopular with Church of England ordinands, it was having to rely on American students from nonconformist traditions who were beginning to change the culture of the college. Trevor’s verdict was that Trinity was in a make-or-break situation, and that the appointment of the next Principal would be decisive for its survival. That was a sobering thought to take into the interview. However, the meeting with the Council went very well. I made it abundantly plain that I was not seeking a new post at the moment, and would have to have very good reasons to move from St Nic’s, where I was very happy. To my utter astonishment, at the end of the day I was summoned to meet the Council again, and was offered the post of Principal of Trinity College, Bristol.

I returned home on the train stunned. Eileen had not bothered to come with me, because neither of us had believed that this move could possibly be right for us. But as I told her about the day’s events we began to see that this could be the next step for us. It was a real and demanding challenge. The more we thought about it, the more we could see that my experience of theological education and parish life fitted me well for the post. We had to admit that once the building project at St Nic’s was complete my presence was not necessary for the next stage, which was to use the buildings for the wider community.

The lay leaders of the church were wonderful in their acceptance of our decision and their willingness to release us once the building work had been completed. The next nine months sped by quickly – we raised the remaining £50,000; indeed we exceeded that amount – and a week of celebrations were held, with the Bishop of Durham leading a service of blessing for the development. The farewells were sad and generous, and we travelled to Bristol with heaviness of heart but much gratitude to God for all we had learned at St Nic’s. We had been blessed beyond belief.

All my fears concerning Trinity College were confirmed when I began my new work as Principal in September 1982. Life at St Nic’s had been tough enough, especially in the first four years, but I seemed to have fallen from the frying pan into the fire. There were structural problems with the constituent colleges in the union. Tyndale Hall, associated with the famous names of Stafford Wright and Jim Packer, was renowned for its emphasis on uncompromising and clear evangelical teaching rooted in the inerrancy of scripture. Clifton Theological College, associated with Alec Motyer, had been established in protest to Tyndale and took a milder line on doctrinal matters, although it was still clearly evangelical. The Women’s College, which was itself an amalgam of St Michael’s House, Oxford, and Dalton House, had buildings across the Downs. Years earlier Oliver Tompkins, Bishop of Bristol, had issued an ultimatum to the three evangelical colleges to amalgamate, and they had done so with a lot of grumbling and not a little feuding.

When I arrived, the amalgamation was not complete. An independent body called the Clifton College Trust still held the deeds of the main building, and was reluctant to surrender them because of suspicions that the ethos of Tyndale would dominate. I found myself regarded with no small suspicion. Older Council members representing the Tyndale tradition were worried that my more open style would undermine a clear-cut evangelical tradition, whilst some of the Clifton College fraternity were fearful that I would be taken over by the dominant Tyndale group. It was clear that if this division were to be overcome – by love and persuasion – it would take some time to achieve.

In the short term the college was in a mess, partly due to its undeserved reputation in the Church of England, which I myself had shared. I realised from my first day that the college was served by an able and highly dedicated faculty who could hold their own with any theological department in the country. Nevertheless, the immediate future was troubling. The break-even financial figure was 105 students, but four weeks before the beginning of term only just over eighty had enrolled to join us. We were heading towards a huge deficit. Of those likely to join us, only forty-eight were ordinands, even though the Church’s allocation of ordinands to Trinity was eighty. The bursar told me that nothing could be done to tackle that year’s deficit.

I was dismayed, but I was also quite sure that a great deal could be done. To begin with, it was important to restore confidence in the college, starting with the staff. Once again the theological vision had to be shared and owned. I was delighted to find no objection to my desire to do something about the worship, which I felt must combine that Anglican balance of word and sacrament. I knew that with talented students the musical standard, and therefore the quality of worship, would steadily improve. When the students arrived our policy was to help them to realise that they had come to the best theological college in England. There was, I felt, a natural and healthy pride in speaking confidently of this. Another part of my job as Principal was to promote the college and make it visible in the structures of the Church. This was done in a variety of ways.

First, I accepted many speaking engagements, as a means to promote the college and to inform as many people as possible that Trinity gave a first-class theological education. Second, I revived a practice which Maurice Wood had developed at Oak Hill, of staff and students spending long weekends in parishes talking about the call of ordination. Third, I kept in close touch with some of the large parishes which were key providers of ordinands, especially at Oxford and Cambridge. My former Principal Michael Green was now at St Aldate’s, Oxford, and his church became a particular quarry for excellent and gifted ordinands.

The students themselves were a good bunch on the whole, but I was worried about the quality of some of the non-ordinands. It is understandable, if not excusable, for Principals to admit people simply to make up numbers. A few of the students at Trinity were plainly unable to cope with the college’s demanding intellectual disciplines, and were there hoping that the course would provide a back door into ordination.

If this troubled me, I had a greater shock when I received worrying reports about one particular student. The first complaints came from two of the women students, who reported that he was sexually harassing them. I called him in at once. He was from a breakaway Christian group, and was hoping to obtain a degree so that he might be ordained in his own Church. He listened to the complaints in an untroubled way, and it was clear that he had pestered the women but was completely free of shame. I gave him a lecture on the kind of behaviour I expected from students at Trinity. However, his view of sexuality appeared to amount to nothing more than an expectation of gratification. He assumed it was obvious that, as a single man, he had sexual needs that should be fulfilled. I asked him to square this with his theology and the discipline of the college. Sending him away again with a warning, I felt with sinking heart that I was encountering a wholly new phenomenon in my experience – a Christian who felt that there were no rights or wrongs in the area of sexual morality. My fears were realised as I and his tutor watched the man’s progress. Besides his inappropriate behaviour with female members of the college he was a practising homosexual. And then he mentioned without a trace of shame that he paid weekly visits to his ‘hooker’ in a nearby village. My mouth must have dropped. Perhaps I had misheard. ‘My hooker,’ he repeated. He did not last long in Trinity after that.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

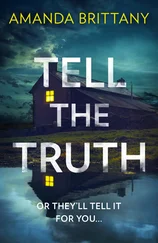

Похожие книги на «Know the Truth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Know the Truth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Know the Truth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.