“You seem very upset,” he says thoughtfully.

Startled, I look at him. “I’m not.”

He tilts his head to the side. “You’re very angry, aren’t you?” he says.

I laugh. “You’re very perceptive, aren’t you?” I say. He writes it down.

Seven red cars, six blue. The day is still. The branches of the trees don’t move. We sit in silence. I turn circles in my chair.

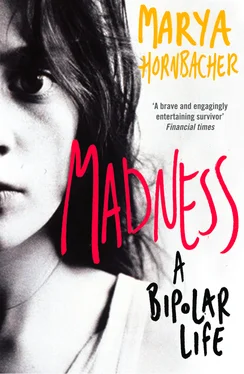

HE’S A FREUDIAN therapist. When he speaks, he asks me about my mother, about my dreams. I wait for him to tell me what’s wrong with me, why I snap into sudden, violent rages, and shut myself in my room with the dresser backed up against the door for days, and disappear in the middle of the night, and stay in constant trouble at school. Why is it that my moods are all over the goddamn map? How come I’m terrified all the time? He sits silently, watching me, saying nothing, fixing nothing. I give up.

He isn’t looking for eating disorders or drinking or drug use. He isn’t looking for mental illness. In truth, he isn’t looking for much at all. One day he slaps his notebook shut. What’s wrong with me? I ask. Am I crazy? I don’t ask that. I think I know.

His wise and considered opinion is that I’m a very angry little girl .

WORD GETS OUT at school that I’m seeing a psychiatrist. My friends avoid the subject. But other kids whisper about it when I come into the room, kids I don’t like and who don’t like me, the rich kids and the snobs. One of them, egged on by the others— Go on, ask her —comes up to me: Is it true you’re, like, crazy?

No, I say, looking down at my desk.

Then why are you seeing, like, a psychiatrist? Isn’t that for crazy people? Isn’t it? Come on, admit it!

I don’t answer. I scribble so hard in my notebook that my ballpoint tears the page. They laugh. I’m a freak, and everyone knows it, including me.

Then suddenly it hits, a massive, crippling headache. My migraines are coming on nearly every day. I stagger into the nurse’s office and collapse on a cot, curled up in a ball with a pillow over my face. The nurse calls my parents. Back home, I lie in the dark, blinds drawn, rabid thoughts and images zipping through my brain, flashes of blinding color and light. I lie there, shivering and sweating as the pain clenches my skull, nearly paralyzed with fear at the fierce throbbing behind my eyes.

My father opens the door slowly, shuts it quietly behind him. I wince at the deafening noise. The bed sags and he leans over me.

“Here,” he says softly. He lays a wet washcloth over my eyes. “How is it?” he asks.

“Horrible,” I whisper.

“I’m sorry,” he says. He lays a hand on my shoulder. “It will go away soon.”

The bed squeaks as he gets up. The door thunders shut behind him. I press my hands to my head.

They take me to doctor after doctor. No one knows what’s wrong. They give me medication, try biofeedback, tell my parents they don’t know. My parents tiptoe through the house, confused, scared. They don’t know what this onset of violent headaches means. Neither do the doctors. Neither do I.

DEATH WOULD BE SO quiet. I hide in the bathroom with an X-Acto knife, making tiny cuts, crosshatch patterns in my thighs. Nothing deep. It helps relieve the pressure, focus the thoughts. I take a sharp breath and breathe out slow. The blood beads along the cuts. I sop it up with Kleenex, the red spreading out over the tissue. I bleed. I’m alive.

AND THEN it’s dinner and my father’s screaming, and my mother’s cold and icy and cruel, and they’re yelling at me and I’m yelling at them—the crazies rise up in my chest and I run away from the table, the rage welled up so far it presses at the back of my throat. I can taste it. My father chases me, hollering. I shriek and run away. We stand face to face, screaming, his face is twisted and I can feel that my face is twisted and I hate him and his craziness and I hate myself for mine, and my mother gets up, walks down the hall, and slams the bedroom door.

My father and I scream each other down until we are exhausted, completely spent. We stand there panting.

“Say,” my father says brightly, perking up. “Want to play Yahtzee?”

“Sure!” I say. And we sit down to play, laughing and having a wonderful time.

AFTER SCHOOL, I open our front door and step inside. The first thing I see is my father, lying on his side on the couch. Light streams in through the long windows, and it takes my eyes a moment to adjust.

I drop my book bag. “What’s wrong?” I say to him from across the room. I don’t want to know what’s wrong. I’m tired of this. You never know which father is going to show up.

He curls up and wraps his arms around his knees.

“I don’t know, Marya,” he says, and starts to cry. “I really don’t know.”

I stare at him flatly. I want to run over there and kick him and pound him until he gets up. When he gets like this, I feel like I am drowning. The hands of his sadness close around my throat and I can’t breathe. I have run out of the enormous love he needs to be all right.

“You know those afternoons,” he asks, drawing a shaking breath, “where you’re just going along, doing fine, and then afternoon comes and it feels like you just got the wind knocked out of you and everything is wrong?” He sighs and slowly pushes himself up so he’s sitting upright. His shoulders are slumped. “That’s all,” he says. “It’s just one of those afternoons.”

We are silent for a minute. Then he lies back down on the couch.

I should say I love him. I should say it will all be all right. But it won’t.

I walk down the hall to my bedroom. I lie down on my side and stare at the wall, the blue-flowered wallpaper next to my nose. Despite my best efforts, I start to cry.

I know those afternoons.

Michigan, 1989

I’m sitting in the study lounge, it’s five A.M., and I have no idea how many nights or days have gone by since I last slept. I’m starving, I’m writing, I can’t stop, don’t want to stop, don’t want to eat, I am possessed by words. I’m at boarding school, an art school where students not yet eighteen spend ten hours a day, six days a week, training, practicing, studying harder than even seems possible, possessed by a desire to make it, to succeed, and I’m surrounded by open books on the study lounge table, my typewriter pouring out a short story, a paper, another, another. I am no longer a fuckup, I’m going to make it, I’m going to ace my classes, I’m going to stay awake forever if I have to, just so long as I write this, whatever it is.

Through the window that looks out over the snowy campus, the light is coming up. The snow is lit a violet-blue, the horizon’s a red-orange line. I sit back in my chair, my body buzzing, this heavenly hum in my head. Paper in stacks on the table. I’m ready for workshop, a fistful of stories in my hand. I’ve read everything for class that I was supposed to and then some. Physics thrills me, math confounds me, the German teacher despairs, but the English teacher, the writer-in-residence, the staff writers who pound us with work, they pull me aside and say: Read it, write it, don’t stop, you’ve got it, you’re going to make it . The magic words, the promise. The hope.

I just give up sleep. I’ve noticed by now that maybe my moods get a little crazier with sleep deprivation. Never mind. The deprivation unleashes a chemical reaction that feeds on itself, so that the less I sleep at night, the less I can sleep the next night, and the next. Night and day reverse themselves—but I’m not going to sleep during the day either. My body clock is no longer keeping time.

Читать дальше