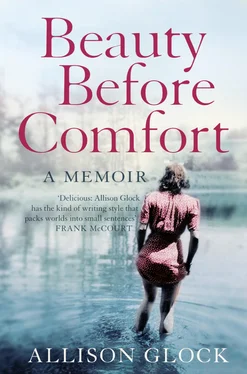

Beauty Before Comfort

A MEMOIR

Allison Glock

For Dixie Jean and Matilda Mercy Law

There’s something about the pottery. You build up quite a companionship, a comradeship, whatever you call it. You take a little bit of clay and mix it up with water and fire it and make something out of it—there’s romance in that. It just gets in your blood.

— ED CARSON, POTTER, 1985

No potter that ever lived can be overlooked, no ware, however humble, can be despised.

— SATURDAY REVIEW, 1879

Everyone has a story to tell. This is the story of my grandmother as she chooses to remember it.

Cover

Title Page Beauty Before Comfort A MEMOIR Allison Glock

Dedication For Dixie Jean and Matilda Mercy Law

Epigraph (a) There’s something about the pottery. You build up quite a companionship, a comradeship, whatever you call it. You take a little bit of clay and mix it up with water and fire it and make something out of it—there’s romance in that. It just gets in your blood. — ED CARSON, POTTER, 1985 No potter that ever lived can be overlooked, no ware, however humble, can be despised. — SATURDAY REVIEW, 1879

Epigraph (b) Everyone has a story to tell. This is the story of my grandmother as she chooses to remember it.

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PERMISSIONS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright

About the Publisher

Bless her heart.

That’s what we say. It’s a catchall.

“Aunt Sue’s getting divorced.” Bless her heart.

“Velma lost her job at the bank.” Bless her heart.

“Crystal backed over the cat with her Cadillac.”

Bless her heart. Bless the cat’s heart.

And so that is what we say when we are told, “Your grandmother is getting worse.”

Bless her heart, we say, although really her heart has never been better. The problem is, as always, in her head.

CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA, 2000

The tiny nursing home bedroom is crowded with family. It is my grandmother’s eightieth birthday and we are trying to get her dressed. Though old, my grandmother is an able woman, so that is not the problem. The problem is style. We are dressing her for a party, her party, and so she wishes to appear festive, and the beige sweater, slacks, and boots her three daughters have selected for her are not cutting it.

“I don’t think that will do at all,” she says, tossing the sweater off the bed. “And no one is wearing those anymore,” she says, squinting and pointing a crumpled arthritic finger at the ankle boots.

She is right, of course. No one wears ankle boots anymore, but her insistence on looking in vogue draws eye rolls and heavy sighs from her girls.

“How about a nice skirt and sweater set?” she suggests. “Something in a yellow, my yellow.” Dutifully, her oldest daughter leaves to go fetch a new ensemble from the mall. Grandmother relaxes and leans back onto her bed. She eyes the group gathered around her, her daughters and their children and various boyfriends, girlfriends, husbands, and wives, and wrinkles her forehead.

“Where’s Glen?”

Glen is her second daughter Jody’s husband, an ex–pro football player prone to complaining.

“He’s at the doctor’s office,” says Jody. “Something’s wrong with his private area.”

“Bless his heart,” says Grandmother.

“He has bad balls,” says Jill, her youngest daughter, cutting right to it.

“Well.” Grandmother laughs. “That’s the saddest story I’ve heard all day.” And then: “Don’t you all have anything better to do today than sit around staring at me? Stay any longer and I’m going to start charging rent.”

Let it be said that there is nothing on God’s green earth my grandmother would consider better than an opportunity to stare at her. She has spent at least seventy of her eighty-two years cultivating stares and making damn sure she has warranted the attention. To gaze at my grandmother is not a passive exercise. She’s no Vermeer. She gives you bang for your buck—be it by making faces, cracking jokes, offering a peek at her undies, or any other shtick she can whip up for your amusement. She’s beyond a pro. To look at my grandmother is to be made to feel special. It’s an actress’s trick, but my grandmother was never an actress, just the daughter of a factory worker born and raised in hillbilly West Virginia (“West-by-God-Virginia,” she calls it), the proverbial coal miner’s daughter, minus the coal and the redemptive sparkly career in Nashville.

“I was born depressed,” she often says, only half-joking. Depression isn’t exactly rare these days in West-by-God-Virginia, as a quick drive through Grandmother’s old neighborhood confirms. Nearly everyone you see is overweight, stuffed full of triple burgers and seasoned fries, living on junk because junk is cheaper than a head of lettuce in most of West Virginia, and when you make shit money at the factory or the mine, you stretch your dollar as much as you can. Besides, a triple burger sure feels better in the belly than a head of lettuce, and most rural West Virginians take what comfort they can get.

Which is why they drink. And smoke. And sit very still on their porches, rickety slices of wood so worn, the nails snag your feet as you shuffle across. They sit very still in their folding chairs, the kind with the itchy plastic-fabric seat you buy at Wal-Mart for $1.99. They sit and they smoke and they pop beers with one hand, pushing down the tab with an index finger so the beer drains quicker from the hole and the cigarette butts drop in more easily once the beer is gone. They sit and wait until they forget what they’re waiting for, and more often than not, they fall asleep in those itchy chairs, the plastic pressing into their doughy legs and arms like cookie cutters.

Sometimes they sing:

Oh, the West Virginia hills, the West Virginia hills, Tho other scenes and other joys may come, I can ne’er forget the love that now my bosom thrills, Within my humble mountain home.

It wasn’t always so bad as now, but West Virginia has never really had it good. It is a hard place, founded on hard land—“The only thing it’s good for is to hold the world together,” goes the joke—and the folks who live there don’t expect any different. Those who do enter into a losing battle with Providence and go mad with the trying, as surely as rocks roll down the mountain.

“I ended up with my nerves,” says Grandmother, describing how her home state shaped her. My grandmother’s nerves are legendary, like Judy Garland’s.

“Bring me a Xanax, would you, dear? Bring me a couple.”

Time was, no one worked a room like my grandmother, Aneita Jean Blair. A slinky redhead with a knowing smile, she sailed through every doorway as if on a wave, ruffling each man and sending them sniffing after her like hounds in heat. In seconds, she would be surrounded. Drinks were brought to her. Cigarettes were lighted by a convoy of matches. She was fanned or draped with sweaters as the climate required. When she rose, all eyes stretched to watch her walk away, hypnotized by the tick-tock swing of her hips. My grandmother always found a reason to look back, and it filled her with a torrid joy to discover the men’s eyes focused on places they shouldn’t have been.

Читать дальше