CLAIRE HARMAN

Fanny Burney

A Biography

To my mother and my father

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

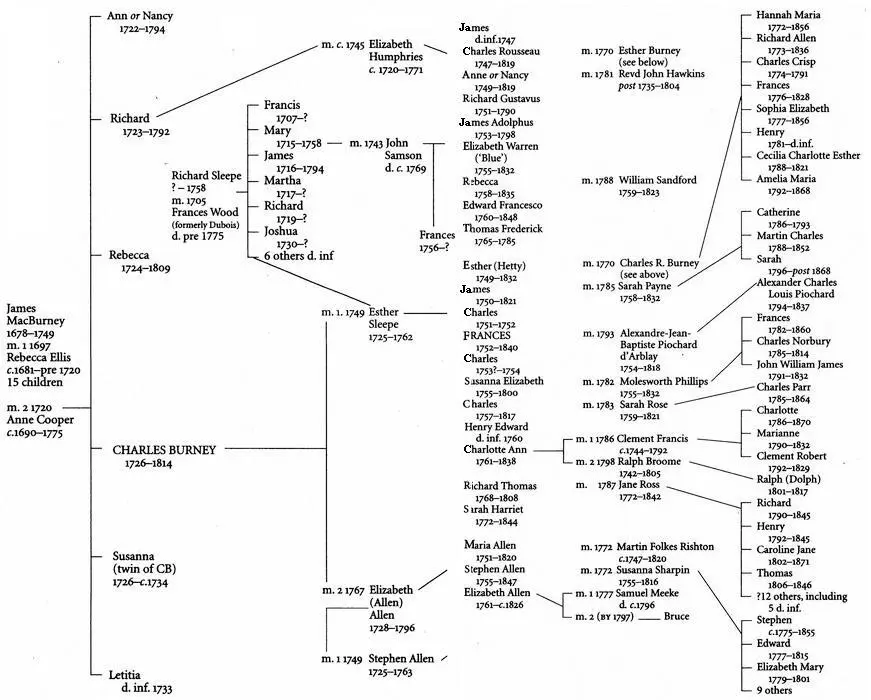

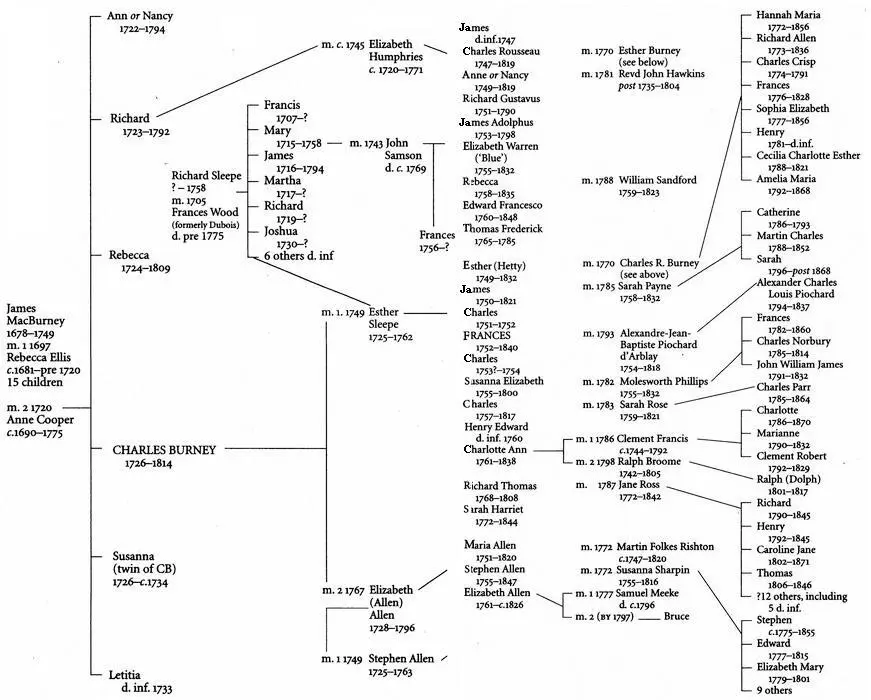

Burney Family Tree

Preface

A Note on Nomenclature

1 A Low Race of Mortals

2 A Romantick Girl

3 Female Caution

4 An Accidental Author

5 Entrance into the World

6 Downright Scribler

7 Cecilia

8 Change and Decay

9 Retrograde Motion

10 Taking Sides

11 The Cabbage-Eaters

12 Winds and Waves

13 The Wanderer

14 Keeping Life Alive

Post Mortem

Appendix A: Fanny Burney Undergoes a Memory Test

Appendix B: Additions to O.E.D. from the writings of Fanny Burney, compiled by J.N. Waddell

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

Praise

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dr Johnson: Ay, never mind what she says. Don’t you know she is a writer of romances?

Sir Joshua Reynolds: She may write romances and speak truth . 1

By dint of outliving her parents, five siblings, husband and child, the novelist Fanny Burney (then Madame d’Arblay) became the caretaker of a vast quantity of family papers in her later years. Her father’s archive alone seemed at one point to be taking over her life, for, as she discovered when she began to sort through his literary remains in the 1820s, he seemed to have ‘kept, unaccountably, All his Letters, however uninteresting, ceremonious, momentary, or unmeaning’. She destroyed quantities of these papers and edited the remaining ones ruthlessly using scissors and heavy black ink; a process she applied to her own archive in the last decade of her life and which was continued after her death by her niece and literary executrix Charlotte Barrett, who pasted over more than a thousand passages in Madame d’Arblay’s diary, and cut out or deleted many others.

Millions of words remain, nevertheless, in tens of thousands of family letters, diaries, memoirs, drafts, notebooks, manuscripts and Fanny Burney’s famous journal covering the period from 1768 until shortly before her death in 1840. The historical and literary importance of the Burney papers was recognised early on. Fanny Burney was one of the best-known and most highly respected novelists of her generation, whose ‘uncommonly fine compositions’ 2 had been admired by writers as diverse as Jane Austen and Lord Byron. She had also led a long and eventful life which brought her into contact with some of the most famous men and women of her time; David Garrick, Samuel Johnson, Hester Thrale, Joshua Reynolds, Richard Sheridan, Edmund Burke, Warren Hastings, Madame de Staël, Talleyrand, Chateaubriand, Napoleon. She was a member of the Royal Household during the period of George Ill’s ‘madness’ in 1788 and a refugee in Brussels during the Battle of Waterloo: she had been an intimate of Dr Johnson in the 1780s, yet lived long enough to meet Sir Walter Scott. When the Diary and Letters of Madame d’Arblay were published in seven volumes between 1842 and 1846, she began a new posthumous career as the leading journalist of the Georgian age.

The first edition of the Diary and Letters was a re-editing, with some deletions, of Burney’s own selection, bequeathed to Charlotte Barrett in 1839 ‘with full and free permission … to keep or destroy’, 3 though Burney must have calculated that the loyal and scholarly ‘Charlottina’ was unlikely to destroy much. The diaries have been in print ever since, in one form or another. Some editions, like Christopher Lloyd’s, 4 were short and sweet, presenting Fanny Burney as a sentimental Regency ‘miss’; others, like Austen Dobson’s of 1904, attempted to put the work in its historical context. Annie Raine Ellis’s 1889 edition of the Early Diary (using material not touched by Mrs Barrett, who began her selection with the publication of Evelina in 1778) was remarkable for its thoroughness and completeness: she included everything she could read of the mauled manuscripts (cut away and pasted over by several generations of the author’s heirs) and included excerpts from Susan and Charlotte Burney’s papers as well.

Ellis’s approach prefigured that of modern scholars, who have laboured to recover every obliteration by means of the latest x-ray and photographic technology. The Burney Project at McGill University is dedicated to this task, which has been going on for some thirty years and is not yet within sight of an end. Joyce Hemlow, the great Burney scholar and biographer, brought out the first of what she expected to be a ten-volume edition of Fanny Burney’s Journals and Letters in 1972. In the event, she oversaw the publication of twelve volumes between that date and 1984 and the present team (under Professor Lars Troide) has published three of a projected further ten volumes of the Early Journals and Letters . Recently there have also been scholarly editions of Fanny Burney’s plays (all but one unperformed in her lifetime), Sarah Harriet Burney’s letters, Charles Burney’s letters and fragmentary manuscript memoirs, and there are plans to publish the letters of Susan Burney and possibly of Charlotte Burney too. By the time the Burney Project has exhausted its rich mine of material, we will know more about this logomaniac tribe and their associates than any other eighteenth-century family.

The very length and thoroughness of Fanny Burney’s journals and letters enforce their standing as a trustworthy record, but while they provide almost unrivalled documentation of fact, they also represent a huge input of authorial control over the interpretation of her life. Basically, a writer who seems to leave no stone unturned is not inviting interpretation at all. ‘Mystery provokes Enquiry’, as Burney herself warned her cousin Rebecca Sandford 5 when she was arguing to keep intact the text of her forthcoming Memoirs of Doctor Burney – a book which, as we shall see, provides countless examples of the manipulation and invention of biographical fact. Burney’s nephew Richard was anxious about the book exposing the family’s humble origins, or, more specifically, his humble origins, since he had omitted to tell either his wife of twenty years or the College of Arms (when he was applying for armorial bearings in 1807) of his grandmother’s ‘undignified Birth’, not to mention – if he knew of it – his own mother’s illegitimacy. Fanny’s refusal to withdraw the Memoirs might seem to cast her in the role of fearless truth-teller on this occasion, but her motive was far more to avoid provoking Enquiry than to dispel ‘mystery’ per se . Her version of her father’s life may not have been the whole truth, but it was full : everything seemed to be accounted for. As a way of controlling information about the family it was highly effective; as proof of Fanny’s veracity it left much to be desired.

The Memoirs have consistently been viewed as an aberration, both of style and technique, an embarrassing filial rhapsody written by a woman in her dotage. Biographers look to Burney’s diaries (especially the early ones) as much purer sources of information: ‘we never turn from the Memoirs to the Diary without a sense of relief’, Thomas Macaulay wrote in his well-known essay on Madame d’Arblay; ‘the difference is as great as the difference between the atmosphere of a perfumer’s shop, fetid with lavender water and jasmine soap, and the air of a heath on a fine morning in May’. 6 But since Memoirs of Doctor Burney was essentially Madame d’Arblay’s autobiography, based on and superseding her journals, they cannot be dismissed quite so readily. Nor does Macaulay’s delight in the heathy freshness of the Diary acknowledge the artificiality of the form which we take to show Fanny Burney at her most open and truthful. Burney began her diary in March 1768, aged fifteen, with a famous address to Nobody, surely one of the most self-conscious, attention-grabbing pieces of supposedly confidential writing ever composed:

Читать дальше