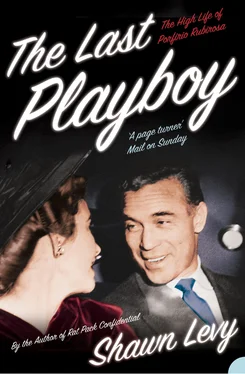

In the time it took for the details of the operation to be worked out, another errand was added to Rubi’s schedule and another conspirator to the plot: Johnny Kohane, a Polish Jew who had also fled Spain without his fortune (some $160,000 in gold, jewels, and currency, he said), was introduced to Rubirosa by Salvador Paradas, who’d replaced him at the Dominican embassy. Kohane had need of his stash, and it was agreed that he would join Rubi on the trip using a passport borrowed from the Dominican embassy chauffeur, Hubencio Matos. In February, the two would-be smugglers got into the embassy’s Mercedes and drove across southern France and, through the Republican-controlled entry point of Cerbere-Portbou, into war-ravaged Spain.

A dozen days later, Rubi returned—alone.

He handed a sack of jewels over to Aldao—a smaller one than the Spaniard expected—and claimed that he’d never been given any inventory to go with it. And he told a hair-raising story about the bad luck he and Kohane had run into outside of Madrid when they were off fetching the Pole’s fortune. They were set upon, he said, by armed men, he wasn’t sure from which side, who chased them and shot at them, killing Kohane. He was lucky, he said, to get out of there with his own skin intact.

What could anyone say? He’d had the moxie to go get the jewels and to get back in one piece. As for Kohane, it was a war zone; he knew it was a dangerous proposition going into it. Suspicion was natural. The car in which Rubi claimed to have been ambushed evinced not a single scratch. But there was no tangible proof that the story, however far-fetched, wasn’t true. Aldao paid Rubi his agreed-upon fee—a platinum-and-diamond brooch—and stewed over the matter for years.

When the situation in Spain finally settled and it was safe to cross back through France, Aldao returned home and looked into the matter of the half bag of jewels and the missing inventory. He wasn’t pleased. There had been an inventory, and Viega had handed it to Rubi; a carbon copy of the original document still sat in the company safe. What the inventory showed was that the bag that left Madrid held jewels worth some $183,000 that never made their way to Aldao in Paris. What was more, a fellow who’d been enlisted to help the Mercedes cross the border swore that he’d never received the platinum-and-diamond bracelet that Aldao had instructed Rubi to give him.

Aldao wrote Rubi in Paris several times to inquire about the missing items but was repeatedly ignored. He sent a Parisian friend to confront Rubi and, as he later declared, his emissary was rudely rebuffed: “The result of the meeting was completely negative, and he was moreover very discourteous to my friend.” Finally, a few years after the fact, he wrote a letter of formal protest to Emilio A. Morel, the Dominican ambassador to Spain. It wasn’t the first Morel had heard of the case—an anonymous letter had found its way to him a year or so earlier, a note, he recalled as so “crammed with inside information” that he believed its author was “a compatriot of Rubirosa’s, actually a principal in the smuggling plan, who felt he had been double-crossed out of a commission from Kohane and took this method of seeking revenge.” Morel dutifully sent notice of these claims against Rubi to the Secretariat of Foreign Relations in Ciudad Trujillo; not only were his inquiries sloughed off, but he, a noted Dominican poet and onetime leader of Trujillo’s own political party, found himself, by virtue of making them, suddenly in the bad graces of the generalissimo. He left Madrid for New York, where he lived out his years in exile. And Aldao got nothing.

Rubi likely had the jewels—and all of Kohane’s assets as well. His finances seemed to have worked themselves out for the decided better. He had been so skint at the start of the year that he would on occasion feign illness so as to summon friends to his house with restorative meals—the only food he could, apparently, afford. After returning from Madrid, however, he spoke of opening his own nightclub and renewed his habit of forming an impromptu club wherever he went; the genius guitarist Django Reinhardt was soon among the players in his ever-expanding, never-ending, ceaselessly moveable feast. Deauville; Biarritz; the French Riviera; and all through the Parisian night: He was ubiquitous, a star. Old friends who encountered Rubi in Paris—among them Flor de Oro and his brother Cesar, now himself a cog in Trujillo’s diplomatic machine—found him exultant, even though they’d been led to expect he’d be sporting a more destitute aspect.

Perhaps news of his self-made success made it back to the Dominican Republic, perhaps he was vouched for by Virgilio Trujillo, but in the spring of 1939, the most amazing bit of fortune landed in his lap: a phone call from Ciudad Trujillo. “The President, who is beside me,” said the official on the other end, “would like to know if you could see after his wife and son, who will arrive in Paris in a few weeks. You’ll have to find a house of appropriate size, accompany them, show them around.”

“I was so stupefied,” Rubi remembered, “that I couldn’t answer straightaway. At first I wondered what sort of trap it was. I couldn’t see one.”

He hurriedly made arrangements to receive Doña Maria and ten-year-old Ramfis and met their boat in Le Havre, where he was startled to find the president’s third wife a full eight months pregnant. Rubi immediately arranged for her to be taken to a clinic where, in comfort, she gave birth to a daughter, Angelita, on June 10. *

In the weeks before and after the birth, Rubi engaged in a full charm offensive, presenting Doña Maria with gifts of jewelry (booty, no doubt, from the Aldao collection) and seeing that the awkward, friendless, unschooled Ramfis was kept happy; the two rode horses together, and it was likely around this time that they began tinkering at polo. As Rubi recalled, the campaign was a success: “Doña Maria wrote to her husband that I was useful, attentive, charming and courteous. Was it due to the sentiment that accompanies pregnancy? Was it due to the change of nations and distance? Trujillo warmed to me.”

The Benefactor had come to recognize that in Rubi he had a truly unique asset: a young, handsome, worldly, cultivated Dominican of notable suavity and negotiable loyalty. Doña Maria, who had no history with the young man, must have impressed her husband with tales of his social skills and tact. And, as Trujillo was soon to discover himself, no Dominican was as enmeshed in the manners and mores of the great European capitals than his scalawag former son-in-law.

The dictator made a grand official tour of the United States in the early part of the summer and then wrote to France to announce that he would be joining his family there. He had his yacht, the Ramfis , sent ahead to Cannes and then sailed to Le Havre himself aboard the Normandie . Rubi was at the dock to meet him. “In the place of a furious father-in-law and an autocrat exasperated by my impertinence,” he recalled, “I found a friendly and agreeable man.”

Trujillo wanted to see the grand sights of Paris—“the elegant Paris, without beans and rice,” as Rubi remembered. But he was perhaps even more interested in the louche part of the city that his former son-in-law, unique among Dominican expatriates, could show him. “Porfirio,” he pronounced, “do not leave my side. I want you to show me everything. You understand? Everything .” Everything included a trip to the top of the Eiffel Tower, where the generalissimo fell under the spell of a girl selling flowers and postcards (presently he courted and bedded her, Rubi remembered, “because he wanted to seduce the loftiest woman in Paris”—“loftiest,” geddit? ). The visit included nights out at Jimmy’s, where the generalissimo, unusually in his cups, declared, “We need a Jimmy’s in Ciudad Trujillo, but much bigger, with four orchestras, gardens and a patio open to the sea.” They moved on to Biarritz, where Trujillo expressed a similar desire to re-create the local hot spots back home. And finally the entire Trujillo party relocated to Cannes and a Mediterranean cruise—all the way to Egypt, they hoped—at the launch of which the dictator whispered to his guide, “Porfirio, I am putting you in charge of this entire voyage.”

Читать дальше