1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...21 Again, what happened next would be in dispute: Either she wrote him to say that she was stricken at the thought of his departure, which assumes his story that they were already on close terms; or he wrote her , out of the blue, if her account of their merely polite relations is more accurate, to express his despair at being separated from her. (Years later, Rubi explained simply, “As in any good script, we found ways of getting letters to each other.”)

Whichever, the next step was indisputably hers. Learning that she would be attending a dance in her honor in Santiago—midway, more or less, between his new post and Trujillo’s ranch—she snuck off on horseback one afternoon and phoned the fortress to invite him. He accepted and, feigning a sore throat and the need to consult a specialist in the city, made his way to Santiago on the day of the dance.

She spied him first in the town plaza, fittingly enough having his boots blacked. Then at the dance, she was seated among the town’s elite when he walked confidently over and asked her to dance. Defying every principle of decorum, they danced together repeatedly—“five times in a row,” as she recalled—and compounded the sensation by speaking in French and then, during the open-air concert following the dance, walking slowly twice around the plaza, albeit under the vigilant eye of her chaperone.

As far as Porfirio was concerned, that was it: “From that moment I was in love, and Flor was as well.”

And that was it as far as Trujillo was concerned as well.

“The dance wasn’t even over when Trujillo heard,” Flor recalled. When she returned to San José de las Matas, she was met with a storm. Her father sent her directly to her room and began grilling his aides to find out who was responsible for the communications between Porfirio and his daughter and who was responsible for letting the banished lieutenant out of the fortress to attend a dance. Flor was terrified by the degree and intensity of his temper and cowered at the door listening as he sputtered to Doña Bienvenida, “She’s gotten herself mixed up with that good-for-nothing lieutenant!”

The next day, an even more dire fate awaited Porfirio: An officer marched into his quarters and announced that he was to be immediately expelled from the army and stripped of all his gear, including, to his special pain, “my uniforms, which I loved so well.”

This was a staggering blow, and he remembered it with high drama: “I was an outcast in my own country. Ignominiously dumped and rejected by the army. Marked on the forehead with the sign of infamy which no one could ignore.” He entertained the thought of exile but he couldn’t leave the island, he said in his most lugubrious voice, because “to leave would be to lose Flor. And to lose Flor would be to die. But to stay would also be to die.”

This was no exaggeration: Trujillo was entirely capable of having his onetime protégé eliminated and, in fact, he dispatched a team of hit men that very afternoon from his goon squad, who roamed the country in ominous red Packards doing the despot’s bidding.

Had he been stationed in any other city, Porfirio might not have survived the day. But San Francisco de Macorís was, of course, his birthplace, as well as the hereditary seat of both sides of his family. “My uncles and my grandfather united in counsel,” he recalled. “My uncle Oscar gave me a well-oiled pistol. A truck was obtained. It took me to a cocoa plantation owned by one of my uncles, Pancho Ariza, about 10 kilometers away.” For more than a week, he hid in an outbuilding on the farm, “staring into space, ruminating on this cascade of catastrophes.”

He was alone in neither his anguish nor his isolation. Before bolting to his hideout, he sent off a note to Flor describing his situation. The emissary who delivered it was tied by Trujillo to a tree and thrashed, while Flor watched in horror. She locked herself away from this frightening tyrant, refusing to speak with him, refusing meals, and writing letter after unsent letter to the young man who had suddenly come to dominate her dreams. Like the heroine of a pulp novel, she would love Porfirio to spite her father.

“Flor had the same strong blood in her veins as her father,” Porfirio would recall. “A will of iron and an indomitable courage guided her. She was the only one who could stand up to her father, even if he was in a state of fury.” When Trujillo sent an intermediary to speak with her, she replied, “Tell my father that I want to marry the man I love, and I will marry him. Otherwise I would not be worthy of being his daughter.”

At least that would be how Porfirio remembered it—or maybe how he imagined it. Flor’s memory was different: a cruelly imposed isolation; the ceaseless slander of the former lieutenant by her father and stepmother; a strange limbo, like being a nonperson.

In his hideaway, Porfirio grew impatient and decided, on instinct, that danger had passed. “It has always been one of my chief principles,” he later confessed. “I will risk everything to avoid being bored.” He rode back to his uncle’s home in town, shocking his family with his sudden appearance. “You don’t have a lick of common sense,” they admonished him.

But, in fact, the worst of it seemed to have passed. Indeed, the lull emboldened Doña Ana Rubirosa to visit Trujillo to plead for her son. As Porfirio recalled it, his mother stood up to the president by asking, “What secret mark is there against our family that Señor Trujillo cannot tolerate that a Rubirosa would dare put his eyes on his daughter?”

The meeting was barely a quarter hour along when Trujillo slapped his desk and declared, “That’s enough! They will marry right away!”

This was like tripping over a winning lottery ticket on the street. From disgrace and near-death, Porfirio was now slated to marry into the first family of the country. Maybe he was in love, truly, or maybe he was too scared to cross Trujillo a second time by refusing Flor, or maybe he was as bold a tíguere as the Benefactor himself. Whichever, he had heedlessly reached for the impossible by making eyes at the president’s daughter and, through charm, gall, and luck, had seized the prize. At twenty-three, he would be wealthier and closer to power than Don Pedro ever had been.

For Flor it was a stunning shock: “Five dances in a row, two circles around a park, an innocent flirtation, and I was to marry a man I scarcely knew!”

Still, marriage would liberate her, she hoped, from a man she knew all too well; as she admitted, she was “wild to leave my prison, to run like hell from Father, an instinct that was to propel me all my life.”

The nuptials were planned for early December at the fateful ranch house where the abortive courtship transpired. Trujillo orchestrated all the details: the invitations, the ceremony, the party. The best man would be the U.S. ambassador, H. F. Arthur Schoenfeld, whom the groom had likely never met. The ceremony would be performed by the archbishop of Santo Domingo. Flor was sent to the capital to have a dress made; her fiancé stayed with his family in San Francisco de Macorís—and was named, if only for the sake of having a title worthy of his entry into the president’s family, secretary to the Dominican legation in London.

On December 2, a caravan of trucks bearing flowers and bridesmaids wended from the capital to the wedding site. The groom was flown in on a military plane. The next day, after the civil and religious ceremonies in the town, the wedding party began late, at 4:30, on what turned out to be a rainy afternoon.

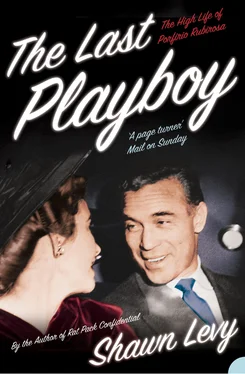

In the photographs of their wedding day, the newlyweds look frightened and tiny, despite their finery and the attendant pomp. Rubi stands with shoulders thrust back and tiny waist forward, a pompadour stiff on his head and a grin set in the baby fat of his cheeks. Flor is a head shorter, with wide-set eyes and a toothy smile; she holds a hand protectively across her breast, cradling her bouquet. They might be a prom couple on their first date.

Читать дальше