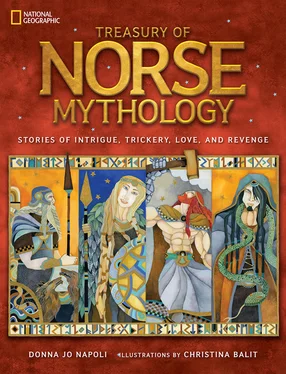

Christina Balit - Treasury of Norse Mythology - Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christina Balit - Treasury of Norse Mythology - Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

a Norse traveler if ever there was one. —CB

Enormous gratitude for guidance throughout this project goes to Professor Scott Mellor of the Department of Scandinavian Studies at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. The author and illustrator also thank the National Geographic team who worked on this project for their resourcefulness, energy, and wisdom: Amy Briggs, Priyanka Lamichhane, Hillary Leo, and David Seager.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Note on Norse Names

CREATION

THE COSMOS

THE GODS CLASH

ODIN’S QUEST

LOKI’S MONSTROUS CHILDREN

WAGERS & TREASURES

SHAPE-SHIFTERS

HEIMDALL’S MANY CHILDREN

FREYJA’S SHAME

THOR’S HAMMER

THOR THE GREEDY

IDUNN’S APPLES

SKADI & NJORD

FREY & GERD

DEATH BY BLUNDER

THE GODS TAKE VENGEANCE

KVASIR’S ENDURING POETRY

DESTRUCTION

AFTERWORD

Map of the Ancient Norse World

Time Line of Norse History

Cast of Characters

Bibliography

Index

About the Authors

INTRODUCTION

During the Middle Ages Latin became the language of writing and of much religious storytelling in many lands of Europe. So, for example, in Germany and France people would speak German or French to friends and business associates, but when they wrote books or told Christian stories, they used Latin. The countries in what is today Scandinavia spoke Old Norse, common to all three countries, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. However, even after Latin writing came to Iceland—which was settled by Norse people—they wrote their own stories in Old Norse, not Latin. In Iceland the tradition of skaldic poetry and song was fundamental to daily culture. People gathered in large halls at any excuse to listen to stories, often because a visiting poet had come to the village. Stories could warm a long cold night, after all. This might well be the reason why some Norse people tenaciously maintained the worldview you will encounter in the stories here until the middle of the 12th century, in opposition to the rising strength of Christianity in neighboring countries.

The Norse stories in many ways reflect the geophysical world the people of Norway and Iceland inhabited. Norway is covered with mountains, the tallest of which are essentially barren—and four are volcanic. Iceland is covered with volcanoes, many of which are active. And both countries have snow and ice in many areas in winter and in some areas even year-round, and each has a long coast lapped by an icy ocean. In such an environment the land and sea themselves must have seemed alive. At any moment the earth might roar, spit fire, and swallow you, or it might shake and an avalanche of snow could smother your homestead. Even a piece of rock, if smacked against a glassy stone, could produce hot sparks that set afire whatever dry twigs were at hand. It’s no wonder then that not just living beings had names, but all sorts of objects had names, too. Bridges and halls, trees and swords, inanimate objects of so many kinds had personalities and powers, and it was important to show respect through calling them by name—and never, never to do so frivolously.

The world must have seemed outrageously dangerous; death waited behind any door, and, oh, how savage that death might be. Nevertheless, these people got in boats and braved seas turbulent with storms as they explored and exploited other worlds. The Norse both paid homage to and defied the unknown. The spirit of courage colors their mythology, even as trickery leads to tragedy. And perhaps facing adversity all the time is at least partly the reason why they had a democratic society in which all free men (not women, and not slaves) had a vote—just as all gods had a vote in the assemblies that the major god, Odin, led. Lives depended on decisions made in communal meetings, so it was best to share both the privilege and the responsibility.

NOTE ON NORSE NAMES

Old Norse used letters that don’t appear in the modern alphabet for English, such as Þ, which indicates the first sound in think; ð, which indicates the first sound in the; and æ, which indicates the first sound in act. They also added marks above or below vowels to indicate a variety of sounds. While these Old Norse alphabetic symbols are beautiful, I feared that using them here would inhibit you from reading passages aloud. I wouldn’t risk robbing you of that joy. So, I have anglicized all proper names here. Further, Norse names often end in r because a final r can be a nominative case marker, showing that the word is the subject of its sentence. Since English does not use case markings on names, for the sake of consistency, I’ve chosen to leave out nominative case-marking final r’s. Thus, “Óðinn, the Alfaðir of the Æsir,” is known here as “Odin, the Allfather of the Aesir.” “Þorr, who swings his hammer, Mjölnir,” is here “Thor, who swings his hammer, Mjolnir.” And so on.

If you would like to know more about Old Norse, please consult a site for the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), such as www.phonetics.ucla.edu/course/chapter1/chapter1.htmlor en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Phonetic_Alphabet. Then use the IPA to help you understand a site on Old Norse, such as www.omniglot.com/writing/oldnorse.htm. Please watch the wonderful video there.

The frost giant Ymir emerged from the melting rivers of Ginnungagap. A daughter sprang from his sweaty armpit; a son, from his feet. The sweet-tempered cow Audhumla licked at the ice until she uncovered the head of the first god, Buri.

CREATION

The north was frozen—snow and ice, nothing more. It was called Niflheim. It was the embodiment of bleakness.

The south was aflame–ready to consume whatever might come. It was called Muspell. It was the embodiment of insanity.

Between them lay a vast emptiness. It was called Ginnungagap. It waited.

In the midst of the northern realm, water bubbled up—in the spring known as Hvergelmir. From it ran 11 rivers, straight down into the void, filling the northern part of Ginnungagap. The cold rivers slowed and thickened, like icy syrup, but a venomous kind of syrup. One that matched the desolate cries of the haunted winds.

The southern part of Ginnungagap was hot, though. Muspell kept it molten, like lava.

So when the gusts from the northern part met the heaving heat from the southern part, the middle of Ginnungagap grew almost balmy. The icy rivers thawed just enough to drip over that wide middle part.

That was enough: The frost giant Ymir stepped out of those drops. From the sweat of his left armpit grew a frost giant son and daughter. Ymir’s feet rubbed together, and another frost giant was born. Ymir’s every move, every thought, resulted in more frost giants. And all of them were spitting mean. What else could they be, given the bitter source of the very liquid in their veins?

Heavenly Movements

The moon and sun

People used to think the sun and moon crossed the sky. But in 1543 astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus argued that the Earth circles the sun, based on his observations of constellations and a lunar eclipse. Later astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler made astronomical measurements, which led to Kepler’s laws of planetary motion around the sun. In 1609 astronomer Galileo Galilei invented the telescope and added support to Copernicus’s model based on observations of the planet Venus.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.