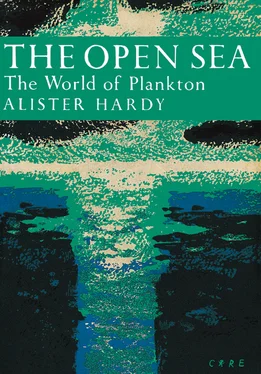

Before going any further I must thank the publishers and editors, not only for all the trouble they have taken over the production of this book, but also for the patience they have kindly shown over my delay in its completion. I accepted their invitation to write it in August 1943, some twelve years ago; it has, however, meant more than the writing. My excuse for its late arrival will be offered after I have made my main acknowledgment.

The value to the book of the remarkable collection of photographs by Dr. D. P. Wilson of the Plymouth Laboratory will be clear to all, but just how wonderful they are and consequently how lucky I am to have them as illustrations, may not at once be fully appreciated by those who are not yet familiar with the living plankton of the sea. Douglas Wilson has long been recognised as the leading photographer of marine life and his beautiful pictures in black-and-white and in colour which graced Professor C. M. Yonge’s The Sea Shore in this series of volumes will, I am sure, have been seen and admired by most of my readers. I, too, am showing some of his studies of the larger forms of life, such as those of cuttlefish or his unusual view of that strange jelly-fish, the Portuguese-man-of-war, taking a meal; it is, however, his photographs of the tiny plankton animals to which I particularly wish to draw attention here. Though they are taken through a microscope, they are photographs of creatures swimming naturally, very much alive and certainly kicking. Never before has such a series of photomicrographs of living members of the plankton been published; they are unique and will, I believe, be of immense value not only to marine naturalists but to all students of invertebrate zoology. They are the fortunate result of a remarkable combination; Dr. Wilson has brought his skill and artistry to work with that very modern invention the electronic flash. For the first time this device has made possible such instantaneous pictures at a very high magnification. It is not only that invention, however, which makes these pictures unique; while others will follow him, Dr. Wilson’s photographs will always have a quality of their own, because he is an artist as well as a scientist. He is not satisfied until he has produced a photograph that has an appeal on the score of composition as well as on that of scientific value. All his photographs except two (the stranded jelly-fish and squid) are of living animals. A few excellent black-and-white pictures by other photographers are included in some of the plates and these are acknowledged in the captions or the text.

It was my hope, and that of the editors, that in addition to his black-and-whites Dr. Wilson would have been able to contribute a series of colour photographs of the living plankton and especially of the richly pigmented animals from the ocean depths. At that time the electronic flash was only just being developed and he felt unable to attempt them. The movement of the ship at sea, he said, would prohibit the use of a long enough exposure to enable the deep-water animals to be photographed in colour by ordinary means; they quickly die and fade, and so must be taken as soon as they are brought to the surface. I had already had some experience in making water-colour drawings of living plankton animals on the old Discovery during the Antarctic expedition of 1925–27; the editors kindly allowed me to undertake a series of such studies to form the accompanying twenty-four colour plates. To obtain and make drawings of the full range of animals which I felt to be desirable, meant a considerable delay and this was added to an earlier postponement of my start on the book caused by my being appointed to the chair of Zoology at Oxford soon after I had accepted the invitation to write it. For several years the work of my new department and research to which I was already committed took all my attention.

All save seven of the 142 drawings in the plates were made from living examples or, in a few cases, from those taken freshly from the net when some deep-water fish and plankton animals were dead on reaching the surface. The seven exceptions, which are noted where they occur, were drawn from preserved specimens but with memories or colour-notes from having seen them alive; I should like to have drawn these too from life, but I could delay the book no longer. It may be of interest to record how the drawings were made. All the animals, except the larger squids and jelly-fish, were drawn either swimming in flat glass dishes placed on a background of millimetre squared paper where they were viewed with a simple dissecting lens, or on a slide under a compound microscope provided with a squared micrometer eyepiece; in either case the drawings were first made in outline on paper which had been ruled with faint pencil lines into squares which corresponded to those against which the specimen was viewed. In this way the shape and relative proportions of the parts could be drawn in pencil and checked and rechecked with the animal until it was quite certain that they were correct. The outline was then gone over with the finest brush to replace the pencil by a permanent and more expressive water-colour line; next all the pencil lines, including the background squares, were rubbed out and the full colouring of the drawing proceeded with. If rough weather at sea made such a course impossible, the living animal would be sketched in pencil, and painted, in perhaps one or two different positions, to give life-like attitudes and colouration without attempting to get the detailed proportions exactly right; it would then be preserved in formalin for accurate redrawing by the squared-background system when calmer conditions returned. The animals I have selected for illustration are mainly either those which are not included in the black-and-white photographs or those for which colour can add supplementary information. I have, for example, drawn some of the transparent but iridescent comb-jellies, but not the transparent and colourless arrow-worms or salps. I am most grateful to the Sun Engraving Company, who made the blocks for the colour plates, for the great care they have taken in making such excellent reproductions.

I must now make special acknowledgments in regard to these drawings. First I must record my thanks to Dr. N. A. Mackintosh, the Deputy Director in charge of the biological research of the National Institute of Oceanography, for kindly allowing me to accompany the R.R.S. Discovery II on two of her biological cruises in the Atlantic in the summers of 1952 and 1954. It is to the Discovery , with all her equipment of deep-water nets, powerful winches and laboratory accommodation, that 71 of these drawings are due, including all those representing the remarkable animals which live in the great depths over the edge of the continental shelf to the southwest of Britain. Without such facilities they could never have been made; actually three of them date back to earlier days when I had the honour of sailing south in the old Discovery in 1925. Next I must thank a number of kind helpers who have sent me living specimens of plankton in specially protected Thermos flasks from many parts of the coast: Mr. J. Bossanyi from Cullercoats, Dr. E. W. Knight-Jones from Bangor, Dr. Richard Pike from Millport, Professor J. E. G. Raymont from Southampton and Mr. R. S. Wimpenny from Lowestoft. Although I made many visits to different places to draw my specimens, there were still a number I could not get myself in the time available; these were supplied by these kind friends who were on the lookout for what I wanted at widely separated points. I am most grateful to Dr. Marie Lebour and to the Council of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom for kind permission to reproduce some of her beautiful drawings of living plankton animals capturing their prey; these, which form my text-figures 26, 27, 35, 40 and 41, were originally published in her papers in the Association’s Journal in the years 1922 and ’23. Then I must thank Sir Gavin de Beer and members of his staff at the British Museum (Natural History), particularly Dr. W. J. Rees and Mr. N. B. Marshall, for kindly allowing me to make many of the black and white drawings in the text from specimens in the museum collections. I am similarly indebted to Dr. J. H. Fraser of the Marine (Fisheries) Laboratory at Aberdeen who has let me draw some of the beautiful plankton animals he has caught to the north and west of Scotland; and to Dr. Helene Bargmann and Mr. Peter David who have also kindly given me much help on looking out specimens from the Discovery collections for me.

Читать дальше