“What’s that got to do with the medicine you took?” Ryan said.

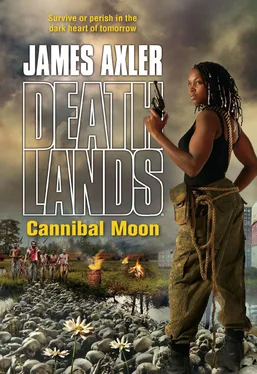

“One drop of her precious blood keeps a hundred of us alive, brother. The word about La Golondrina’s healing power spread from pack to pack all across Deathlands. Cannies started pilgrimaging from the farthest corners to find her and be saved from the Gray Death. They’re still coming.”

Ryan turned and gave Mildred a dubious look.

“There had to be a Patient Zero, Ryan,” Mildred said with conviction. “An initial human case. If this woman survived, whether because of the freezing or thawing process, or the duration of her cryosleep, or some other unknown factor, she had to have produced antibodies to the disease. If oozie-infected blood can kill, blood with oozie antibodies can save.”

“Do you have to take the medicine more than once to be protected?” Mildred asked Junior. “Does its effect wear off over time?”

“Don’t know. I’ve only taken it the once. Four months ago. I haven’t gotten any worse.”

“It may not be a complete cure,” Mildred said. “In low concentrations, it could be just a temporary treatment, a palliative that has to be repeated to keep the final stage at bay.”

“How do we find this freezie?” Ryan asked the cannie.

Junior cackled, sensing a sudden turn of fortune. “You don’t,” he said. “Not without me to guide you.”

“Yeah, right.”

“You need me, brother. If what we did to you norms down in the valley was hell, the homeland in Siana is hell on wheels. You’ll never get close to La Golondrina without my help.”

“Let’s talk outside a minute,” Mildred told Ryan.

As they left the cave, Junior’s shrill pleas echoed against their backs. “Feed me! You promised you’d feed me!”

Squinting at the bright morning light, Mildred and Ryan stared across the wide river valley. They could see fires still burning out of control in the no-name ville.

“What happens to me is no longer the issue,” Mildred said gravely. “I don’t matter anymore.”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s a much bigger problem, Ryan. Until now the oozies kept a lid on the population and spread of cannies. Until now it was one hundred percent fatal. If there’s a treatment that lifts that lid, there’s nothing to stop the disease and cannies from overrunning the continent. Every norm in Deathlands is a potential new cannie or cannie victim.”

“How can we follow a stinking bastard who’d eat his own mother if given the chance?”

“We don’t have any choice, other than hiding our heads in the sand. We’ve got to turn off the spigot once and for all, or every night is going to be like last night—or worse. We’ve got to find La Golondrina and kill her.”

“Jak’s gonna take the news about Siana triple hard,” Ryan said. “And the whole crew is gonna to be mighty unhappy if we bring Junior back alive.”

“Ville folk aren’t going to like it much, either. We have to convince them that he’s too valuable to chill.”

“Tough sell all around.”

As if to underscore his point, a familiar cry echoed in the cave behind them. “Feed me!”

“Junior won’t survive the journey unless we let him eat a little something,” Mildred said.

“Little is what he’s going to get. If we keep the bastard hungry, we keep him honest.”

Naked to the waist except for her Army-issue bra, Mildred squatted beside the creek, sloshing her T-shirt in a shallow pool. She washed off the crusted vomit and gore, then wrung it out and pulled it back on, still wet and clinging. No way she could wash the smell from the inside of her nose. The cannie cave’s greasy pall of melted fat and burned flesh clung to her skin and hair, as well. Inside and out, she felt soiled, contaminated.

She inventoried her physical state with as much professional detachment as she could manage. In the wake of the forced feeding and projectile vomiting, her stomach ached like she’d swallowed, then expelled, a five-pound cannonball. There was no evidence of fever, though. According to Junior Tibideau, he had come down with symptoms overnight, after his first contact with the Siana pack. No flesh-eating on his part.

“Woke up cannie.”

An unlikely outcome, Mildred knew.

If oozie virus was inhaled or absorbed through the skin, it would take several days, perhaps even a week or two, to build up to the point where increased production of white blood cells would cause his body temperature to rise to the fever point. She also knew that brain lesions and radical changes in behavior didn’t happen suddenly in the absence of violent head trauma. Mildred concluded that Junior was flat-out lying, trying to deflect the blame for his vile actions, which were more voluntary than he wanted to let on; this in order to minimize or eliminate punishment. The wretched, weak-willed bastard didn’t want to admit that he had been so easily seduced by the cannie lifestyle.

Junior had proved himself a liar, so how could she believe him about the existence of the oozie medicine?

He wasn’t the only source of that information. The cannie with the caved-in head had bragged about it before Junior had dosed her, while they were still in complete control of the situation. So it couldn’t have been a lie calculated to keep the miserable bastards alive, or to make her a compliant member of the pack by dangling survival under her nose.

Before they left the cave, Mildred and Ryan had decided that she would have the only close contact with Junior. They couldn’t be sure how contagious the infection was; and she was already exposed to the max. Mildred checked his shoulder and found a superficial flesh wound, which she cleaned, but didn’t bother to stitch.

Then at blasterpoint they turned him loose for a couple of minutes on the dead ’uns.

It was triple hard to watch him go at it. He fed like a ravening animal on his own, downed packmate. Mildred couldn’t help but think she might be looking at her own future, and even more horrifying, the future of her companions. She had driven Junior off the charred corpse with a sharp blow of her pistol butt on the top of his head and a single, barked command. “Enough!”

She picked up her gunbelt and rose, still dripping, from the creekside.

Thirty feet upslope, Ryan guarded the cannie with his SIG-Sauer. Junior’s wrists were tied behind him. A thick, four-foot length of tree limb was thrust between his back and crooks of his arms. This served to keep the prisoner bent slightly at the waist, off balance; he couldn’t run five steps without falling on his face. Which made him much easier to handle. They didn’t have to keep him on a short leash.

Under a clear blue midday sky they continued across the Grand Ronde valley. In the distance, the ville’s dirt-and-log berm was still burning, sending up clouds of brown smoke and soot. As they neared the encampment’s perimeter, they could hear sounds of weeping, coughing and the intermittent crunch of shovels gouging the stony earth. When the blinding smoke shifted, it revealed a line of women, children and oldies digging a long communal grave in the hard-pan.

On the other side of the trench, more than twenty bodies were lined up on the ground, shoulder to shoulder. Young, old, male, female. Hacked. Shot. Incinerated. They had manned the barricades and defended the rutted lanes with their lives. Some had died trying to escape the cannie wolf packs. Mildred knew there were many more ville folk missing. On their descent of the valley, she and Ryan had come across numerous sets of tracks in the sand, twin, parallel tracks made by bootheels, the last impressions of unconscious victims as they were dragged away.

Downwind of the diggers, a wide, shallow pit belched low flame and coils of black smoke. Doused with gasoline, the heaped cannie dead were burning like garbage on a midden.

Читать дальше