Mrs Phipps looked across at her grandson and shook her head. ‘You father had such hopes for you, Gavin. The Brigade … maybe the Foreign Office afterwards …’ She sighed. ‘But since you ask, what I had in mind was Sidney Torch and his Light Orchestra. I know Sidney, and he’d come down here for me in an instant, I feel sure of that. They have such beguiling music, darling, just the sort of thing to attract the traditional holidaymaker. He came down here once before, years ago, and you know, they even got up in the aisles and danced!’

‘With Danny Trouble they’ll never sit down,’ said Gavin tartly. ‘What this place desperately needs is something for the younger crowd.

‘You know, Granny’ he went on, ‘this is 1959 – people don’t want to dance cheek to cheek any more, they want rock and roll!’

‘I suppose you may be right,’ conceded his grandmother, who was becoming alarmed at the prospect of having to confess to Temple Regis that the Pavilion Theatre would remain dark through the summer season. ‘We do need something new. People got fed up with Arthur doing his West End Life – that’s why he ran away, you know. They got up and started catcalling.’

‘It wasn’t Suki Raffray, then? Why he ran away?’

‘IT WAS NOT SUKI RAFFRAY!’ shouted Mrs Phipps. ‘Don’t mention that name again!’

‘Then you agree, Granny? That Danny and the boys can come for the six-week season?’

‘What else can I do?’ said Mrs Phipps, shaking her head so hard her fine silvery hair escaped its pinnings. ‘I have no alternative.’

‘You won’t regret it, Gran.’

Mrs Phipps shuddered as she reached again for Plymouth’s most famous export.

‘I feel as though someone just walked over my grave,’ she said.

THREE

The atmosphere in the editor’s office at the Riviera Express was as it always was – dusty – but the moment the newspaper’s chief reporter walked in it got dustier.

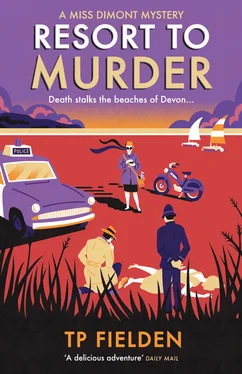

Judy Dimont was everything an editor could wish for – a brilliant mind, a dazzling shorthand note and charm enough to entice whole flocks from the trees. Yet, as Rudyard Rhys raised his eyes from the task in hand, a particularly recalcitrant briar pipe, he could see none of this. Before him stood a striking woman of indeterminate age dressed vaguely in a macintosh with its belt pulled tight at the waist, and with a waft of corkscrew curls slipping joyously from the restraints of a silk scarf. A faint scent of rum entered the room with her.

‘Got the fishermen,’ said Judy Dimont, a trifle dreamily. ‘What extraordinary men they are! Why, do you know …’

‘Rr … rrrr,’ growled her editor, whether by way of approval or dissent it was hard to tell, but enough to douse Miss Dimont’s tribute to those in peril on the sea.

Rhys returned to his pipe. ‘There was a murder while you were out on your jolly boating trip,’ he said, a nasty edge to his voice. ‘As my chief reporter I should have liked you there.’

‘There was a force nine out beyond the headland,’ said Miss Dimont, not a little proud of her early morning exploits. ‘Rather difficult to spot a murder from there. Anyway, who …’

‘Had to send him ,’ said Rhys, nodding towards a corner of the room. A young man half rose from his seat and, with a slight smile, gently inclined his head. In a second the chief reporter had it summed up – wet-behind-the-ears recruit, probably the son of a friend of the managing director, going to be useless, a dead weight, another failed experiment in attracting the nation’s young talent into local journalism.

Miss Dimont was not without prejudice but in general she was kind. She did not feel kind this morning.

‘Well then, let him write it up,’ she said, eyeing not without prejudice the item which hung round his neck and which looked suspiciously like an old school tie. ‘I’ve got this feature to write and then, if it’s OK with you, Mr Rhys, I’m going home. I was up at three this morning to catch the tide.’

For a man who once had worn Royal Navy uniform himself, Rhys showed a surprising lack of interest over the vicissitudes of the ocean. ‘Give him a hand,’ he ordered, and dismissed them both with the swish of a damp page-proof.

Pushing up the spectacles which adorned her glorious nose, Miss Dimont stepped, with an audible sigh, out into the corridor. The last thing she wanted – another trainee reporter dumped on her!

‘Have you found yourself a desk?’ she inquired shortly, not even bothering to look over her shoulder as she strode into the newsroom.

‘They … they told me to sit opposite you,’ said the young man. ‘The other lady, er …’

‘Betty.’

‘Yes, Betty’s … um … I think she’s … er, not quite sure. I think she’s been sent elsewhere.’ The words seemed hesitant but he appeared pretty self-assured. ‘Newbury something.’

‘Newton Abbot?’ she said.

‘That’s about the size of it,’ said the young man. ‘She didn’t seem too happy.’

This did not please Miss Dimont one bit. Betty Featherstone was effectively her number two and, though uninspired, was a useful reporter who did her share of filling the copious news pages which made up the weekly digest of events in Devon’s prettiest town. Having her dispatched to the district office was a blow. It would increase the chief reporter’s workload and, at the same time, require her to shepherd this innocent lamb through his first weeks on the paper until he got the hang of it.

Or disappeared.

The young man sat down opposite her. ‘Erm, we haven’t been introduced. Valentine is the name.’

‘Judy Dimont, Mr Valentine. Welcome to the Riviera Express .’ The words didn’t have quite the cheery ring they might, but then she was not used to rum for breakfast. She felt tired and wanted to go home to Mulligatawny.

‘Er, Valentine’s the first name,’ the boy said.

‘Surname?’

‘Waterford.’

‘Well, that’ll look pretty as a front-page byline,’ she said, not entirely kindly. ‘Raise the tone a bit.’

‘I was thinking of shortening it to Ford. It’s a bit of a mouthful,’ he said apologetically.

‘Well, you won’t need to do anything with it if you don’t write up your murder,’ said Miss Dimont crisply. ‘No story, no byline. You do know what a byline is?’

‘Window dressing,’ said Waterford. ‘For the reporter, it’s compensation for not being paid properly. A bun to the starving bear.’

His words caused Miss Dimont to look at him again. Could, for once, the management have recruited some young cannon fodder who actually had a few brains?

‘Makes the page look nice, makes the reading public think they know who wrote the story,’ he went on, smiling. ‘A byline makes everybody happy.’

Good Lord, thought Miss Dimont, her head clearing rapidly. He’s what, twenty-two? Obviously just finished National Service. How come he knows so much about journalism?

‘How come you seem to know so much about …’

‘Uncle in the business,’ said Valentine, looking with unease at the large Remington Standard typewriter in front of him. He carefully folded a sheet of copy paper into the machine, took out a brand-new notebook and started to tap. Very slowly.

Obviously he does not need my help, thought Miss Dimont, and set about her own preparations to bring to life the world of Cran Conybeer and his lion-hearted friends.

Just then Betty Featherstone wafted by, attracted by the mop of tousled hair atop Valentine Waterford’s handsome young head. Despite her marching orders she was evidently in no hurry to catch the bus to Newton Abbot.

It was a sight to behold when Miss Dimont got to work. She hunched over her Quiet-Riter and the words just flowed from her flying fingers. Her corkscrew hair wobbled from side to side, her right hand turned the pages of the notebook while the left continued to tap away, and her lovely features sometimes pinched into an unattractive scowl when she found herself momentarily lost for a word or phrase. But as the paper in her typewriter smoothly ratcheted up, line by line, the story of the extraordinary events of her pre-dawn foray in the English Channel came gracefully to life.

Читать дальше