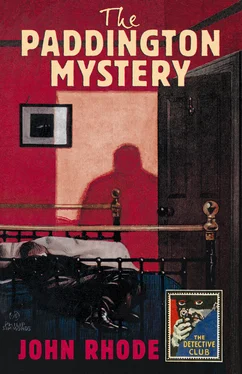

Very deliberately, as though embarking upon an undertaking which required skill and concentration for its successful accomplishment, he climbed out of his chair, grasped the candlestick in an unsteady hand, and staggered towards the door which led into the bedroom at the back of the house. He negotiated the narrow doorway, laid the candle down on the dressing-table, and began to fumble at his collar and tie. All at once the extreme desirability of seeking a prone position impressed itself upon him. Curse these clothes! They seemed to hang upon him as an incubus, resisting every attempt of his groping fingers to divest himself of them. He flung his coat and waistcoat upon a chair, and turned with a sigh of relief towards the bed. He must lie down for a bit, his head was beginning to ache, he could finish undressing when he felt better.

The candle threw a flickering light across the room. He could see a dark mass upon the bed, doubtless the suit he had thrown upon it when he was dressing that evening. He put out his hand to drag them off, and even as he did so stopped suddenly, as though a cold hand had gripped him. That dark mass was not his clothes at all. It was a man lying on his bed.

The first shock over and certainty established, he chuckled foolishly. A man! If it had been a woman, now! Vere, perhaps, come all this way to beg his forgiveness. Of course, it couldn’t be. How could she have got in? He had given her a latchkey once, but the first thing she had done had been to lose it. How on earth had this fellow got in, then?

Harold returned to the dressing-table to fetch the candle. This sort of thing was insufferable. Holding the candle over the bed he began to apostrophise his visitor.

‘Look here, my friend, I don’t so much mind finding you in my rooms like this, but I do draw the line at your turning me out of my own bed. Sleep here if you must, but sleep on the sofa next door and let me have the bed like a good fellow. I’ve had rather a hectic night of it.’

The form on the bed made no sign of having heard him. Harold put his hand on its shoulder and withdrew it suddenly. The clothes he had touched were oozing water. With a thrill of horror Harold bent over still further and put the candle close to the man’s face. His eyes were open, glassy, staring at nothing. Shocked into horrified sobriety, Harold thrust his hand beneath the man’s soaked clothing, seeking the skin above the heart. It was cold and clammy, not the slightest pulsation could he feel stirring the inert body.

For an instant he paused, fighting the sensation of physical sickness that surged through him. Then, as he was, stopping only to fling round him his discarded overcoat, he rushed from the house and dashed frantically to the police station.

IT was not until a week afterwards that Harold found leisure or courage to call upon Professor Lancelot Priestley. Leisure, because his time had been fully occupied, and that most unpleasantly, in attending the inquest and being interviewed by pertinacious officers who displayed an indecent curiosity as to his habits and acquaintances. Courage—well, Professor Priestley happened to be April’s father, and they had last parted as a result of a most regrettable incident.

Professor Priestley had been a schoolfellow of his father, and the two had kept up a certain intimacy through early life. But while Merefield the elder had settled down comfortably to country solicitorship, Priestley, cursed with a restless brain and an almost immoral passion for the highest branches of mathematics, occupied himself in skirmishing round the portals of the Universities, occasionally flinging a bomb in the shape of a highly controversial thesis in some ultra-scientific journal. How long this single-handed warfare against established doctrine might have lasted there is no telling. But with characteristic unexpectedness Priestley solved his personal binomial problem by marrying a lady of some means, who, having presented him with April, conveniently died when the child was fourteen, perhaps of a surfeit of logarithms.

Upon his marriage, Priestley had settled down, to use the term in a comparative sense. That is to say, he exchanged his former guerilla warfare for a regular siege. No longer were his weapons the bayonet and the bomb; he now employed the heavy artillery of lectures and weighty articles, with which he bombarded the supporters of all accepted theory. He claimed to be the precursor of Einstein, the first to breach the citadel of Newton. And as none of his acquaintances knew anything about these matters, he was not subjected to the annoyance of contradiction in his own house.

The two friends, Merefield and Priestley, continued to see one another at frequent intervals. Priestley would take his little daughter down to stay in the country, Merefield would bring his boy up for a week in town, when April and Harold, much of an age, would be sent to the Zoo and Madame Tussaud’s and Earl’s Court Exhibition, under the careful tutelage of April’s governess. Their parents, presumably, alternated the conversation between the calculus of variations and the rights of heirs and assigns over messuages and tenements.

It was perhaps unavoidable that one of those curious understandings, whose secrets adults fondly imagine are securely hidden from their offspring, should have been arrived at between the two. And in this case the understanding was less vague than usual. Anything indeterminate was a source of horror to the mathematician; anything loosely worded a reproach to the solicitor. It is not to be supposed that an agreement was actually drawn up, sealed, signed and delivered. But both these fond parents had firmly made up their minds that Harold was to marry April.

Their children, more accommodating than children are apt to be, fell in willingly enough with this plan. It was, of course, only conveyed to them in hints, increasing in clarity as they approached years of discretion. The whole business was taken for granted; it was a postulate to which there could be no possible alternative. Then came the war, the death of Merefield the elder, and Harold’s strange aberration from his appointed path.

There is no need to trace the widening of the breach, the outspoken condemnations of Professor Priestley, the subtler scorn of April. The crisis came one afternoon, when Harold had called at the house in Westbourne Terrace after lunching particularly well. Aspasia’s Adventures had been published a few days previously, and the occasion had called for a bottle by way of celebration. The first thing that met Harold’s eye on the table of the Professor’s study, into which he had been shown, was a copy of this sensational volume—it should be remarked that the publishers had seen fit to embellish it with a jacket upon which the heroine was displayed in male company in a lack of costume definitely startling. Harold’s interview with April’s father ended with the statement by the latter that he could not possibly contemplate the marriage of his daughter to a man whose dissipated manners had culminated in the production of such pornographic twaddle as this, to which Harold, emboldened by champagne, had retorted that April appeared to be adequately consoled by the company of that young cub Evan Denbigh, and that he proposed to go his own way as he pleased, anyhow. This short and heated interview had taken place some six months previously, and had been the last occasion on which he had passed the portals of the house in Westbourne Terrace.

But it was now a very chastened Harold who pressed the bell-push, with that nervous touch which betrays a secret hope that the bell has not rung, and that a few more minutes of respite must therefore elapse before the ordeal. But, light as had been his touch, the bell had tinkled far away in the lower regions, and Mary, the old parlourmaid, to whom much was forgiven, appeared with startling suddenness.

Читать дальше