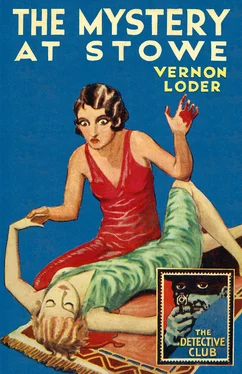

Vernon Loder was among the early wave of Golden Age writers. A popular and prolific author, he wrote 22 titles during the decade immediately preceding the Second World War. The Mystery at Stowe was Loder’s first work, initially published in 1928 by Collins as a full-priced novel, and reissued the following year in their popular and eye-catching new sixpenny crime list, The Detective Story Club.

In the original Preface to this reissue of The Mystery at Stowe , the Club’s editor, F. T. (Fred) Smith described Vernon Loder as ‘one of the most promising recruits to the ranks of detective story writers’. While Loder was a firm believer that the task of the detective fiction writer was not only to mystify but to entertain, he realised that the key essential for success was brilliant detective work and made this the chief feature of the story. The setting is a traditional country house party, favoured by Golden Age writers and one to which Loder returned in several later novels. The action features a diverse group of party guests, and takes place mostly within Stowe House and its grounds. One of the guests is found dead in her bedroom at dawn, lying beside an open window. She had been killed by a small poisoned dart, found lodged in her upper back. Amateur sleuth Jim Carton is in the mould of the new breed of ‘hero’ detectives, arguably first modelled by E. C. Bentley’s creation Philip Trent—intelligent and engaging, yet modest, sensitive and fallible. He brings the added expertise of having once been an Assistant Commissioner in West Africa, where he had investigated numerous criminal cases, and gained knowledge of the natives’ subtle use of little-known poisons in committing murder using a blow-pipe and poisoned darts.

Whereas Loder’s murder method had also featured a couple of years earlier in Edgar Wallace’s The Three Just Men (1926), his mystery is intriguingly plotted and seemingly impenetrable, and red herrings and blind alleys abound. With twists and turns throughout, excitement and tension steadily mount, with a denouement true to Golden Age conventions. The finale is truly surprising and revelatory. One reviewer has described the solution as ‘borderline genius yet utterly insane’ (John F. Norris—Pretty Sinister blogspot, April 2013).

Stowe is a well-written and skilfully constructed story, which blends action, detection, human interest and romance to form a varied and effective first mystery novel. It also contains some witty dialogue and observations, with Loder’s use of names and places which nod to other Golden Age writers and novels of the same period an amusing feature for genre enthusiasts.

Vernon Loder was one of several pseudonyms used by the hugely versatile and fecund Anglo-Irish author Jack Vahey (John George Hazlette Vahey), 1881–1938. In addition to the canon of Loder titles between 1928 and 1938, Vahey wrote initially as John Haslette from 1909 to 1916, resuming writing in the late 1920s as Anthony Lang, George Varney, John Mowbray, Walter Proudfoot and Henrietta Clandon. Born in Belfast, Jack Vahey was educated in Ulster and for a while in Hanover, Germany. He began his working life as an architect’s pupil, but after four years switched careers and sat professional examinations with a view to becoming a chartered accountant. However, this too was abandoned, when Vahey took up writing fiction. He married Gertrude Crewe, and settled in the English south coast town of Bournemouth. His writing career was cut short by his death at the relatively young age of 57.

All of the Loder novels were published by Collins in the UK. From 1930 onwards, his works were published under their famous Crime Club imprint. Several of his early novels (between 1929 and 1931) were also published in the US by Morrow, sometimes under different titles. Loder had several series detectives—Inspector Brews, Chief Inspector Chase and later Donald Cairn—but Jim Carton makes his sole appearance in Stowe . The publisher’s biographical note on Loder which appears in Two Dead (1934) mentions that his initial attempt at writing a novel (apparently never published) was during a period of convalescence in bed. Various colourful claims are made of Loder: he once wrote a novel on a boarding-house table in twenty days, which was serialised in both England and the US under different names, and published in book form in both countries; he worked very quickly, and thought two hours in the morning quite enough for anyone; also, he composed directly on a typewriter, and did not ever re-write.

Loder’s entertaining and skilful novels are written in the simple, direct, smooth-flowing and occasionally jocular style favoured by Golden Age authors. His hallmark distinctives include complex and ingenious plots, full of creativity and invention, leading up to a major surprise and twist in the closing pages. A recurring theme often found in his works is that of the victim who falls prey to his own scheming. Despite his early popularity, Loder never quite achieved the first rank of detective novelists and the enduring status and fame which accompanies this, although original Collins jackets demonstrate that he was well-reviewed: ‘The name of Mr Loder must be widely known as a reliable and promising indication on the cover of a detective story’ ( Times Literary Supplement ); ‘Successive books by Vernon Loder confirm the impression gathered by this reviewer that we have no better writer of thrill mystery in England’ ( Sunday Mercury ); ‘…just the effortless telling of a good story and meticulous observation of the rules’ (Torquemada in the Observer ). Nevertheless, his works have remained out of print since the 1930s, and have been the purview of Golden Age collectors, among whom he has a dedicated following, with first editions scarce and commanding high prices.

Now Vernon Loder is emerging from obscurity—and rightly so. Despite the rather scant and cursory attention he has received in the major detective fiction commentaries, Loder has a number of proponents, including leading US writers on Golden Age fiction, John Norris and Curtis Evans, and deserves a better place in Golden Age posterity. I particularly recommend searching out some of his later titles— Whose Hand (1929), The Vase Mystery (1929), The Shop Window Murders (1930), Death in the Thicket (1932) and Murder from Three Angles (1934). Loder deserves to be rediscovered and enjoyed by a new readership, and this reissue of his important first novel The Mystery at Stowe augurs well for the revival of his popularity.

NIGEL MOSS

October 2015

MR Vernon Loder is one of the most promising recruits to the ranks of detective story writers, and this novel The Mystery at Stowe augurs well for his future popularity. He certainly knows how to provide a mystery baffling enough to satisfy the most exacting reader. He holds too a very definite opinion, with which we are wholeheartedly in agreement, that the task of the writer of mystery stories is not only to mystify, but to entertain. Consequently he has enlivened the more serious business of detection by the inclusion of several amusing characters.

But while appreciating to the full the entertainment value of the thriller, Mr Vernon Loder fully realises that nothing succeeds so well as really brilliant detective work, and that is the chief feature of his story. The reader may justly suspect every character of the murder of Mrs Tollard in that pleasant country house, and interest and suspense are cleverly maintained to the very last, when a well-engineered surprise awaits us. Jim Carton himself is a most interesting detective to follow. He is an unusual type and brings to the problem the fresh and alert mind of an Assistant Commissioner in West Africa. In that capacity he has investigated many criminal cases among natives. The fact that a tiny poisoned dart was found buried in the victim’s back specially interests one who has special knowledge of African natives and their subtle use of little-known poisons in committing murder.

Читать дальше