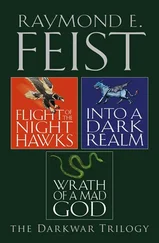

RAYMOND E. FEIST

Talon of The Silver Hawk

Book One of Conclave of Shadows

HarperVoyager

An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

First published by HarperVoyager 2002

Copyright © Raymond E. Feist 2002

Cover Illustration © Nik Keevil

Raymond E. Feist asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780002246811

EBook Edition © AUGUST 2012 ISBN: 9780007373802

Version: 2014–09–05

For Jamie Ann For teaching me things I didn’t know I needed to learn

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Part One: Orphan

Chapter One: Passage

Chapter Two: Kendrick’s

Chapter Three: Servant

Chapter Four: Games

Chapter Five: Journey

Chapter Six: Latagore

Chapter Seven: Education

Chapter Eight: Magic

Chapter Nine: Confusion

Chapter Ten: Decision

Chapter Eleven: Purpose

Chapter Twelve: Love

Chapter Thirteen: Recovery

Part Two: Mercenary

Chapter Fourteen: Masters’ Court

Chapter Fifteen: Mystery

Chapter Sixteen: Tournament

Chapter Seventeen: Target

Chapter Eighteen: Choices

Chapter Nineteen: Defence

Chapter Twenty: Battle

Chapter Twenty-One: Hunt

Epilogue: Scorpion

Keep Reading

Continue the Adventure …

Acknowledgments

About The Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

‘Death stands above me, whispering lowI know not what into in my ear …’

Walter Savage Landor

H E WAITED.

Shivering, the boy huddled close to the dying embers of his meagre fire, his pale blue eyes sunken and dark from lack of sleep. His mouth moved slowly as he repeated the chant he had learned from his father, his dry lips cracking painfully and his throat sore from intoning the holy words. His nearly black hair was matted with dust from sleeping in the dirt; despite his resolve to remain alert while awaiting his vision, exhaustion had overcome him on three occasions. His normally slender frame and high cheekbones were accentuated by his rapid weight loss, rendering him gaunt and pale. He wore only a vision seeker’s loin cloth. After the first night he had sorely missed his leather tunic and trousers, his sturdy boots and his dark green cloak.

Above, the night sky surrendered to a pre-dawn grey and the stars began to fade from view. The very air seemed to pause, as if waiting for a first intake of breath, the first stirring of a new day. The stillness was uncommon, both unnerving and fascinating, and the boy held his breath for a moment in concert with the world around him. Then a tiny gust, the softest breath of night sighing, touched him, and he let his own breathing resume.

As the sky to the east lightened, he reached over and picked up a gourd. He sipped at the water within, savouring it as much as possible, for it was all he was permitted until he experienced his vision and reached the creek which intersected with the trail a mile below as he made his way home.

For two days he had sat below the peak of Shatana Higo, in the place of manhood, waiting for his vision. Prior to that he had fasted, drinking only herb teas and water; then he had eaten the traditional meal of the warrior, dried meat, hard bread and water with bitter herbs, before spending half a day climbing the dusty path up the eastern face of the holy mountain to the tiny depression a dozen yards below the summit. The clearing would scarcely accommodate half a dozen men, but it seemed vast and empty to the boy as he entered the third day of the ceremony. A childhood spent in a large house with many relatives had ill prepared him for such isolation, for this was the first time in his existence he had been without companionship for more than a few hours.

As was customary among the Orosini, the boy had started the manhood ritual on the third day before the Midsummer celebration, which the lowlanders call Banapis. The boy would greet the new year, the end of his life as a child, in contemplating the lore of his family and clan, his tribe and nation, and seeking the wisdom of his ancestors. It was a time of deep introspection and meditation, as the boy sought to understand his place in the order of the universe, the role laid before him by the gods. And on this day he was expected to gain his manhood name. If events went as they should, he would rejoin his family and clan in time for the evening Midsummer festival.

As a child he had been called Kieli, a diminution of Kielianapuna, the red squirrel, the clever and nimble dweller in the forests of home. Never seen, but always present, they were considered lucky when glimpsed by the Orosini. And Kieli was considered to be a lucky child.

The boy shivered almost uncontrollably, for his paltry stores of body-fat hardly insulated him from the night’s chill. Even in the middle of the summer, the peaks of the mountains of the Orosini were cold after the sun fled.

Kieli waited for the vision. He saw the sky lighten, a slow, progressive shift from grey to pale grey-blue, then to a rose hue as the sun approached. He saw the brilliance of the sun crest the distant mountain, a whitish-golden orb that brought him another day of loneliness. He averted his eyes when the disc of the sun cleared the mountains, lest his sight flee from him. The trembling in his body lessened as the sun finally rose sufficiently to begin to relieve the chill. He waited, at first expectantly, then with a deep fatigue-generated hopelessness.

Each Orosini boy endured this ritual upon the midsummer day close to the time of his birth anniversary in one of the many such holy places scattered throughout the region. For years beyond numbering boys had climbed to these vantage points, and men had returned.

He experienced a brief moment of envy, as he recalled that the girls of his age in the village would be in the round house with the women at the moment, chatting and eating, singing and praying. Somehow the girls found their women’s names without the privation and hardship endured by the boys. Kieli let the moment pass: dwelling on what you can’t control was futile, as his grandfather would say.

Читать дальше