The policewoman sighed: “There’s been a murder.”

“A … what?”

“Just who are you?” asked the policewoman.

“Patrizio Baudo. I live here,” he said, and raised one hand with a fingerless glove to point at the windows of his apartment.

Inspector Rispoli focused on the man’s face, so that she could actually see her reflection in his sunglasses. “Patrizio Baudo? I think that … come with me.”

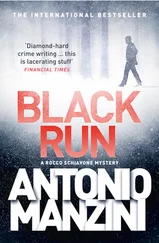

He hadn’t had time to change yet. Sitting in his cycling jersey and shorts across from the deputy police chief, Patrizio Baudo had however taken off his sunglasses and helmet. He’d handed his bike over to a police officer; you don’t leave a piece of fine equipment like that, easily worth six thousand euros, out on the street, even if you do live in Aosta. His face was pale, and there were two red stripes beneath his eyes. He looked like someone had been slapping him around for the past ninety minutes. He sat there in a daze, slack-jawed, staring blankly across the desk at Rocco. He was trembling, hard to say whether in fear or from the cold, and held his hands between his legs, still clad in leather cycling gloves. Every so often he’d raise his right hand and touch the gold crucifix that hung around his neck. “Let me get you something warm to put on,” said the deputy police chief as he picked up the receiver of his desk phone.

Phascolarctos cinereus . Commonly called the koala bear. Patrizio Baudo resembled nothing so much as the little Australian marsupial, and that was the first thing that had come into Rocco’s mind when the man walked into the room and shook his hand. The second thought was to wonder why he hadn’t already detected that resemblance from the photographs scattered throughout the apartment. The proportions, he replied inwardly. You can see them much better in person. The eyes are so much better than a camera lens at judging space and units of measurement. All it took was a quick glance at the jug ears, the small, wide-set eyes, and the oversize nose square in the middle of the face, practically covering the small, lipless mouth. To say nothing of the weak, receding chin. Every detail of that face shouted koala . There were, of course, differences. Aside from the differences in diet and habitat, what distinguished the animal from Patrizio Baudo was the hair. The little marsupial had lovely, cottonball hair, while Patrizio was bald as a billiard ball. This was a habit of Rocco’s, to compare human faces to the features of a given animal. Something that dated back to his childhood. It all started with a gift his father had given him when he turned eight: an encyclopedia of animals that had a section full of wonderful illustrations done at the end of the nineteenth century, depicting lots and lots of birds, fish, and mammals. Rocco would sit on the carpet in the family’s little Trastevere living room and spend hours poring over those drawings, memorizing names, amusing himself by finding resemblances with his teachers at school, his classmates, and people in his neighborhood.

Casella walked in with a black jacket and gave it to Patrizio Baudo, who immediately wrapped it around his shoulders. “How … how did it happen?” he asked in a faint voice.

“We still don’t know.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Patrizio’s dead, dark little eyes suddenly flamed up, as if someone had lit a torch in the pupils.

“It means we found her hanged in your den.”

Patrizio put his gloved hands over his face. Rocco went on. “But the situation isn’t entirely clear.”

The man took a deep breath and looked at the policeman, his eyes filled with tears. “What do you mean by that? What isn’t clear?”

“It’s not clear whether your wife killed herself or was murdered.”

He shook his head and ran his hand over his weak chin. “I don’t … I don’t understand. She hanged herself … how could someone else have possibly killed her? Are you saying someone hanged her? Please, I don’t understand …”

Caterina Rispoli came in with a cup of tea. She gave it to Patrizio Baudo, who thanked her with a half smile but didn’t drink any. “Please explain, Dottore. I don’t understand …”

“There are details concerning the death of your wife that just don’t make sense. Details that make us think it might have been something other than a suicide.”

“What details?”

“We’re strongly inclined to think that it’s been staged somehow.”

Only then did Patrizio Baudo gulp down a mouthful of tea, which was immediately followed by a shiver. He once again touched the crucifix with his gloved right hand. Rocco shot Officer Casella a look. “I’ll have you taken home now. Please, take anything you’ll need. But I’m afraid you won’t be able to stay in your apartment. The forensic squad is conducting an examination. Do you have somewhere you can stay?”

Patrizio Baudo shrugged. “Me? No … maybe at my mother’s?”

“All right. Officer Casella will accompany you to your mother’s house. Here in Aosta?”

“Not far. In Charvensod.”

Rocco stood up. “We’ll keep you informed, don’t worry.”

“But who was it?” Baudo suddenly blurted. “Who could have done such a thing? To Esther … to my Esther …”

“I promise I’ll do everything I can to find out, Signor Baudo. I assure you.”

“I don’t believe it. I can’t believe it. Just like that? From one moment to the next? What is this? What’s happening?” He looked around in bewilderment. Caterina had dropped her gaze, Casella was fixated on some indeterminate point on the office ceiling, while Rocco stood there, chilly and detached. Deep inside him a rage was burning that wasn’t all that different from what the other man felt. Patrizio finally burst into tears. “I can’t take this …” he murmured under his breath, crumpled up on his seat like an abandoned rag.

Rocco put a hand on his shoulder. “Tomorrow I’m going to need you, Dottor Baudo, once you feel a little stronger. We believe that there was a theft from your home.”

Patrizio went on sobbing. Then the emotional tempest subsided as quickly as it had come. He sniffed and nodded to the deputy police chief. “Not tomorrow. Now.”

“Right now you’re too—”

“Right now!” said Patrizio, leaping to his feet. “I want to see my home. I want to go home.”

“If nothing else, you can get changed, no?” said Casella, inappropriately. Rocco incinerated him with a single glance. “He can’t go around dressed like a clown, you know,” Casella added under his breath, justifying his comment to Rispoli.

“All right, Dottor Baudo, let’s go,” said Rocco, taking the cup still full of tea and setting it down on the desk.

“Don’t call me dottore . I never went to college.” He strode briskly out of the room, followed by Rocco and Inspector Rispoli.

Italo drove the police BMW without revving the motor, carefully avoiding the worst potholes. It was easy to avoid the worst potholes in Aosta. Because there weren’t any. At least not compared with the streets of the Italian capital, where the native Romans had given a name to every lurch and jolt and where trying to accelerate on the sanpietrini —the Romans had named their cobblestones after St. Peter—was an excellent way of procuring a spontaneous abortion. Patrizio Baudo looked out the passenger window. “I’m starting to hate this city,” he said.

“I can understand that,” replied the deputy police chief from the backseat.

“I’m from Ivrea. But you know how things are, right? I found a job here and then … Esther’s from here, from Aosta. We were great friends, you know? I mean, before we got married. I don’t even know how it happened. First we were friends, then we fell in love. Then all the rest.”

Читать дальше