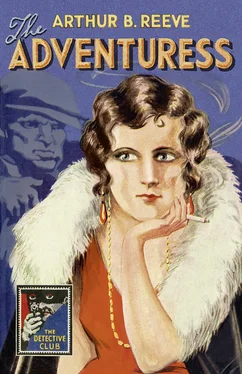

Despite a general curtailment in Reeve’s short story output during his film writing years, a new full-length novel commissioned by the respected New York publishing house Harper & Brothers was published in 1917 as part of their centenary year celebrations. The Adventuress , concerning a murder in a munitions firm and the theft of a new invention, the ‘telautomaton’, was serialised initially in the Chicago Examiner for, they claimed, ‘the highest price ever paid this author for a novel’. UK rights were sold to Harpers’ future sister company, William Collins, who also bought the final two collections of Cosmopolitan shorts, The Treasure-Train and The Panama Plot . Meanwhile Harpers went on to publish ten more books with Reeve, plus an impressive twelve-volume reprint collection, The Craig Kennedy Stories (1918), which included the bulk of the Cosmopolitan shorts (although not the newly released The Panama Plot ), the novel The Gold of the Gods, the Elaine novelisations and the two non-Kennedy books, Guy Garrick and Constance Dunlap . The widespread success of this set at the time has ensured that the early Craig Kennedy books have remained relatively easy to track down, whereas The Adventuress and the novels that followed it remain generally much harder to find.

With his Cosmopolitan run having ended in 1918, the 1920s saw Reeve diversifying. More film work included writing for stage sensation Harry Houdini, with their first movie, The Master Mystery , also having the distinction of featuring the first on-screen robot, Automaton ‘Q’; he even wrote Westerns. A return to magazines, newspapers and lucrative pulps saw Craig Kennedy appearing in both cosier romantic mysteries and stories set in the country as well as harder-edged gangster stories and syndicated comic strips. Technology remained a constant theme—the film serial Craig Kennedy: Radio Detective (1926) capitalised on a very topical medium, and the novel Pandora (1926) featured synthetic fuel and an atomic bomb.

By the end of the decade Reeve was focusing more on real-life criminology. He became ‘radio detective’ himself when NBC signed him in 1930 to write and host Crime Prevention Program , an advisory series in conjunction with the NYPD. It rejuvenated his journalistic career: more radio followed, he published his first non-fiction book, The Golden Age of Crime , an examination of racketeering and other consequences of Prohibition since its introduction in 1920, and he covered high-profile crime cases in newspapers, including the Lindbergh kidnapping case that had inspired Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934).

Reeve’s final novel, The Stars Scream Murder (Appleton-Century, 1936), was in terms of the science one of his least plausible—astrology!—and was also Craig Kennedy’s swan song. The flap of the dust-wrapper bore an enthusiastic summary of Reeve’s achievements since creating his scientific detective a quarter of a century earlier:

‘More than a million copies of Arthur B. Reeve’s “Craig Kennedy” books have been sold in the United States to date and almost as many in Great Britain. fn1They have been translated into practically every language, including one book into ancient Korean.

‘ The Stars Scream Murder, probably the first astrological detective novel ever published, maintains Mr Reeve’s long record of firsts. His first story employed the use of tire treads in detection, a method which has now borne fruit in the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the U.S. Department of Justice, with its astounding file of the treads of all tires manufactured. The first story ever to use the now well-known dictagraph was written by Mr Reeve even before the scientific journals had described it. He also wrote the first story based upon the Freudian theory and psychoanalysis. Pioneering in this manner, he has created a new type of detective story with a host of imitators. He himself considers his most important influence the helping along of the creation of a scientific department in every one of the country’s modern detective headquarters.

‘It is hardly necessary to recount the innumerable titles which have made his name a household word as a master of detective fiction, nor to recall his various motion picture serials, such as The Exploits of Elaine , The Master Mystery , Terror Island , etc., which so many of us remember. He was in radio in the days of its infancy, his N.B.C. Crime Prevention Program having achieved particularly wide attention.’

Arthur B. Reeve died just four months later, on 9 August 1936, of cardiac asthma, aged only 55. As John Locke wryly observes, ‘Reeve all but took Kennedy to the grave with him. Most of the books were already out of print; the remainder soon joined the silence. Reeve went from American institution to forgotten man of antiquity virtually overnight.’ The only reprieve was a 26-part television series starring Donald Woods, Craig Kennedy, Criminologist in 1952, although it was pretty generic and largely ignored the science angle that had distinguished the original Craig Kennedy from his peers.

Reeve had undoubtedly struck a chord with readers and had modernised crime fiction to make it feel relevant and exciting; but sadly nothing dates quite as quickly as yesterday’s cutting-edge science. Craig Kennedy now reads more like a parody than a visionary detective. But if you can transport your mind back 100 years, The Adventuress might still ‘unfold new delights to readers of exciting mysteries’, as the review in the London Globe newspaper maintained, and will hopefully inspire readers to investigate more of the forgotten work of Arthur B. Reeve and his ‘American Sherlock Holmes’.

DAVID BRAWN

October 2016

To the real reader of detective fiction the name of Craig Kennedy must be almost as well known as that of Bulldog Drummond, or Sherlock Holmes himself. He has taken his place among the great crime investigators of our literature, not simply because he is the ‘hero’ of some of the world’s best mystery novels, but because he is distinctly an individual. His personality and his methods are his own, and except perhaps in his success as a solver of crimes he cannot be said to resemble any other detective hero. He is essentially the scientific sleuth; not only in his logic, but in the more melodramatic sense of the word—in his laboratory experiments.

Mr A. B. Reeve, the creator of Craig Kennedy, seems to be a very mine of ingenuity. He introduces into his stories strange cyphers, diabolical machines, subtle poisons, and a hundred and one new weapons for his murderer, but he never becomes cheaply sensational. His farthest flights of imagination appear rational to his readers, for he unfolds his story so cunningly and with such a conviction of truth.

At the present time, when the crime novel is at the height of its popularity and authors vie with each other in turning out more and more complex plots, it is refreshing to find someone like A. B. Reeve, who is content to entertain and mystify us without putting us through an examination in mathematics or psychology.

One need only read The Adventuress to test the truth of this assertion; it is of the author’s best and, unlike many of Craig Kennedy’s cases, is a full-length novel and not a short story; but the one admirable feature of an A. B. Reeve book is that it makes one forget office, household duties, everything one wants to forget, for several glorious hours in a new world of romance and mystery.

CHAPTER I

THE MYSTERY OF THE ‘SYBARITE’

Читать дальше