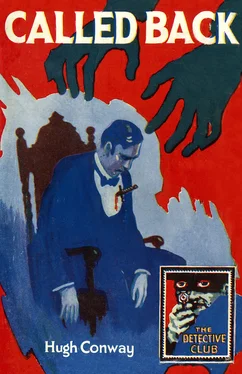

Who knows? It is not impossible that, had he lived and written for another two or three decades, Fargus would have ranked alongside such immortals as Collins, Stevenson, M.R. James and Conan Doyle. As a result of his untimely death, his legacy was less striking. Nonetheless, Called Back deserves to be read again, not merely as a reminder of an unfulfilled talent, but in its own right, as lively entertainment from a bygone age.

MARTIN EDWARDS

February 2015

www.martinedwardsbooks.com

CHAPTER I

IN DARKNESS AND IN DANGER

I HAVE a reason for writing this tale, or it would not become public property.

Once in a moment of confidence, I made a friend acquainted with some curious circumstances connected with one period of my life. I believe I asked him to hold his tongue about them—he says not. Anyway, he told another friend, with embellishments, I suspect; this friend told another, and so on and on. What the tale grew to at last I shall probably never learn; but since I was weak enough to trust my private affairs to another I have been looked upon by my neighbours as a man with a history—one who has a romance hidden away beneath an outwardly prosaic life.

For myself I should not trouble about this. I should laugh at the garbled versions of my story set floating about by my own indiscretion. It would matter little to me that one good friend has an idea that I was once a Communist and a member of the inner circle of a secret society—that another has heard that I have been tried on a capital charge—that another knows I was at one time a Roman Catholic, on whose behalf a special miracle was performed. If I were alone in the world and young, I dare say I should take no steps to still these idle rumours. Indeed, very young men feel flattered by being made objects of curiosity and speculation.

But I am not very young, nor am I alone. There is one who is dearer to me than life itself. One from whose heart, I am glad to say, every shadow left by the past is rapidly fading—one who only wishes to live her true sweet life without mystery or concealment—wishes to be thought neither better nor worse than she really is. It is she who shrinks from the strange and absurd reports which are flying about as to our antecedents she who is vexed by those leading questions sometimes asked by inquisitive friends; and it is for her sake that I look up old journals, call back old memories of joy and grief, and tell everyone, who cares to read, all he can possibly wish to know, and, it may be, more than he has a right to know, of our lives. This done, my lips are sealed forever on the subject. My tale is here—let the inquisitive take his answer from it, not from me.

Perhaps, after all, I write this for my own sake as well. I also hate mysteries. One mystery which I have never been able to determine may have given me a dislike to everything which will not admit of an easy explanation.

To begin, I must go back more years than I care to enumerate; although I could, if necessary, fix the day and the year. I was young, just past twenty-five. I was rich, having when I came of age succeeded to an income of about two thousand a year; an income which, being drawn from the funds, I was able to enjoy without responsibility or anxiety as to its stability and endurance. Although since my twenty-first birthday I had been my own master, I had no extravagant follies to weigh me down, no debts to hamper me. I was without bodily ache or pain; yet I turned again and again on my pillow and said that my life for the future was a curse to me.

Had Death just robbed me of one who was dear to me? No; the only ones I had ever loved, my father and mother, had died years ago. Were my ravings those peculiar to an unhappy lover? No; my eyes had not yet looked with passion into a woman’s eyes—and now would never do so. Neither Death nor Love made my lot seem the most miserable in the world.

I was young, rich, free as the wind to follow my own devices. I could leave England tomorrow and visit the most beautiful places on the earth: those places I had longed and determined to see. Now, I knew I should never see them, and I groaned in anguish at the thought.

My limbs were strong. I could bear fatigue and exposure. I could hold my own with the best walkers and the swiftest runners. The chase, the sport, the trial of endurance had never been too long or too arduous for me—I passed my left hand over my right arm and felt the muscles firm as of old. Yet I was as helpless as Samson in his captivity.

For, even as Samson, I was blind!

Blind! Who but the victim can even faintly comprehend the significance of that word? Who can read this and gauge the depth of my anguish as I turned and turned on my pillow and thought of the fifty years of darkness which might be mine—a thought which made me wish that when I fell asleep it might be to wake no more?

Blind! After hovering around me for years the demon of darkness had at last laid his hand upon me. After letting me, for a while, almost cheat myself into security, he had swept down upon me, folded me in his sable wings and blighted my life. Fair forms, sweet sights, bright colours, gay scenes mine no more! He claimed them all, leaving darkness, darkness, ever darkness! Far better to die, and, it may be, wake in a new world of light—‘Better,’ I cried in my despair, ‘better even the dull red glare of Hades than the darkness of the world!’

This last gloomy thought of mine shows the state of mind to which I was reduced.

The truth is that, in spite of hope held out to me, I had resolved to be hopeless. For years I had felt that my foe was lying in wait for me. Often when gazing on some beautiful object, some fair scene, the right to enjoy which made one fully appreciate the gift of sight, a whisper seemed to reach my ear—‘Some day I will strike again, then it will be all over.’ I tried to laugh at my fears, but could never quite get rid of the presentiment of evil. My enemy had struck once—why not again?

Well I can remember his first appearance—his first attack. I remember a light-hearted schoolboy so engrossed in sport and study that he scarcely noticed how strangely dim the sight of one eye was getting, or the curious change which was taking place in its appearance. I remember the boy’s father taking him to London, to a large dull-looking house in a quiet dull street. I remember our waiting in a room in which were several other people; most of whom had shades or bandages over their eyes. Such a doleful gathering it was that I felt much relieved when we were conducted to another room in which sat a kind, pleasant-spoken man, called by my father Mr Jay. This eminent man, after applying something which I know now was belladonna to my eyes, and which had the effect for a short time of wonderfully improving my sight, peered into my eyes by the aid of strong lenses and mirrors—I remember at the time wishing some of those lenses were mine—what splendid burning glasses they would make! Then he placed me with my back to the window and held a lighted candle before my face. All these proceedings seemed so funny that I was half inclined to laugh. My father’s grave, anxious face alone restrained me from so doing. As soon as Mr Jay had finished his researches he turned to my father—

‘Hold the candle as I held it. Let it shine into the right eye first. Now, Mr Vaughan, what do you see? How many candles, I mean?’

‘Three—the one in the centre small and bright, but upside down.’

‘Yes; now try the other eye. How many there?’

My father looked long and carefully.

‘I can only see one,’ he said, ‘the large one.’

‘This is called the catoptric test, an old-fashioned but infallible test, now almost superseded. The boy is suffering from lenticular cataract.’

Читать дальше