‘You might well cock your lug holes,’ he says. ‘This little number represents everything I feel like doing at the moment. A return to nature and a life free from stress and strain. I can almost hear the rooks crowing.’

‘Cocks crow,’ I say. ‘Rooks caw. What is it, Sid? Put me out of my misery.’

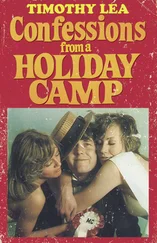

‘A camping site by the seaside,’ says Sid. ‘What could be simpler?’

‘You mean caravans?’ I ask.

‘Caravans, tents, anything. All you need is a bit of water and somewhere for them to have a Tom Tit and clean their Teds. A field will do. It’s a doddle to look after, and all the time you’ve got the sky as a ceiling above your head, You wake to the sound of birdsong. You’re in the middle of people who are enjoying themselves. And the moment was never riper. With this once great country of ours temporarily in diarrhoea straits, more and more families are taking holidays at home, discovering the joys of their own countryside.’

‘Where are you thinking of doing this?’ I ask.

Sid rubs his hands together. ‘Funny you should say that. When it came to a site I really fell on my feet.’

‘They look as if something fell on them,’ I say – somebody once described Sid as comatose and hammer toes.

‘Don’t take the piss,’ says Sid. ‘You’re going the right way to get a button down hooter when you go on like that. Just ask intelligent questions and you might learn something.’

‘Which one of Madame Necroma’s relations owns a field near the sea?’ I ask.

‘Her aunt,’ says Sid. ‘Wait a minute! How did you know she had a relation who owned a field?’

‘I’ve got mystic powers,’ I say. ‘I can foretell every time you are going to be conned. How much did you pay for this place?’

‘I haven’t paid anything yet,’ says Sid. ‘I’m not a fool! I’m not going to buy it without seeing it. It might be totally unsuitable. Really, Timmo, you do get up my bracket when you imply that I’m some kind of Charlie when it comes to sussing out job opportunities.’

He is still fuming when Dad comes in. I am a bit choked because I had not wished to be caught in a situation which might alarm my sensitive parent. ‘What have you two skiving ’arstards been doing?’ he says as I thrust my arms out of sight beneath the table.

‘Nothing,’ I say automatically.

‘I can believe that,’ says Dad. ‘Now, I’m going to say two words that should strike terror into your hearts: hard work.’

‘Why? Do you want us to translate them for you?’ says Sid.

Dad is clearly feeling righteous after putting in one of his irregular days at the lost property office and does not warm to Sid’s merry quip. ‘Bleeding disgrace!’ he snarls. ‘A working man does an honest day’s labour and he has to put up with two of his family behaving like bloody kids. Haven’t you got anything better to do than hop about in sacks?’

‘Ah – yes,’ says Sid. ‘Sacks. Well, we’re trying to get fit, aren’t we?’

In fact, what happened is a bit more complicated than that. The fuzz take most of Sid’s clothes with them when they leave the caravan and when Madame Necroma’s old man comes in and finds a naked Sid trying to pull up the trousers of a bloke wearing handcuffs he gets the wrong idea. You can’t blame him really. I mean, we live in disturbing times when what went for our grandfathers does not even make us think about coming. When he throws us down the steps of the caravan we are in a bit of a quandary and it is just as well that there is this pile of sacks lying behind the coconut shy. We slip two on sharpish and hop off home. Probably the most knackering experience I have ever undergone, especially coming after Millie – not that I did come after Millie. I am pretty certain that we came at the same time. Anyway, it helped to disguise Sid’s naughty parts and the fact that I was wearing handcuffs.

‘I’ll tell you how to get fit,’ says Dad. ‘Do some bleeding work! The country can’t afford to support grasshoppers any more.’

‘If it can support you, it can support anybody,’ says Sid. ‘Grasshoppers, arse hoppers, you name it!’

‘Hello, dear,’ says Mum, coming in with a tray of tannic poisoning – or tea as she calls it. ‘Did you get your certificate all right?’

‘Oh!’ says Sid. ‘Been down to Doctor Khan, have we? How long did he give you this time?’

‘He doesn’t know what he’s talking about!’ says Dad. ‘He’s useless if you don’t wear a turban.’

‘Don’t be like that,’ says Sid. ‘That curry powder did wonders with your warts.’

‘And you know who owns the supermarket where I had to buy it?’ complains Dad. ‘Only his blooming brother-in-law. I remember when you used to get your stuff at a chemist. He told Mrs Kedge to wear a lentil poultice and it was leaking out of her knickers all down the high street.’

‘Walter!’ Mum jerks up the spout of the tea pot in protest.

‘Well, it’s true. It’s no good trying to draw a veil over these things. It’s like this business of having to pay for your medical certificate. It’s profiteering off the sick and needy.’

‘So you’ve been down the library all day?’ accuses Sid. ‘Queueing up with the dossers to have a crack at the page three nude in the Sun .’

‘Some swine tore it out!’ says Dad. ‘That’s nice, isn’t it? Taxpayers’ money and all. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was one of Khan’s lot. They like white women.’

‘Well, that’s only fair,’ says Sid. ‘I mean, you like black women, don’t you? I remember how choked you were when you thought those African birds were going to have to cover up their knockers on the telly.’

‘Sidney!’ says Mum.

‘Nearly turned him against the monarchy, it did,’ says Sid. ‘He couldn’t make up his mind whether to write to Buckingham Palace or Bernard Delfont. In the end he chose Bernard Delfont because he was more influential.’

‘It was the artistic licence I was worried about,’ says Dad.

‘You ought to be more worried about the TV licence,’ says Mum. ‘We’ve had three reminders and you still haven’t done anything.’

‘What have you got there?’ asks Dad. Like a berk, I have raised my hands to grab the tea and Dad has clocked my wrists.

‘He’s got his cufflinks tangled,’ says Sid. ‘Nice, aren’t they? A bit on the large side but handsome.’

‘It’s nothing to be alarmed about,’ I say. ‘This bird thought I was something else – I mean someone else.’

‘Picked you out in an identity parade, did she?’ says Dad. ‘Don’t worry, my son. They’ll never make it stick. What did you do? Nick her handbag. Where is it?’

‘I didn’t nick anything,’ I say.

‘You don’t have to lie to me, son,’ says Dad. ‘I’m your father. I’ll stick by you. We may have our ups and downs but when the chips are down we Leas stick together.’

‘Look –’ says Sid.

‘Shut up!’ says Dad. ‘You led him into this, I suppose? Made him the catspaw for your evil designs. Played on his simple nature.’

‘What do you mean simple?’ I say.

‘Your father’s right, dear,’ says Mum. ‘Don’t let them put words into your mouth. Say you never touched the girl.’

‘I didn’t touch the girl,’ I say. ‘I mean, not like that I didn’t.’

‘Of course, it could go badly with him,’ says Dad. ‘There’s his criminal record to be taken into consideration.’

‘Don’t be daft!’ I say. ‘The only criminal record I’ve got is “The Laughing Policeman”.’

‘He laughs in the teeth of danger!’ says Sid. ‘Makes you proud, doesn’t it? Shall I start piling the furniture against the door? How long do you think we’ll be able to hold out? Better nip out and get a few cans of beans before they get round here.’

Читать дальше