And so, I think fate has been good to you. I am glad you died this morning.

I must have been deep in my thoughts and memories when the Señorita came into the room, for I had heard no rustle or footfall. Now, however, I turned from my window-gazing to look again on the face of Lessingham where he lay in state, and I saw that she was standing there at his feet, looking where I looked, very quiet and still. She had not noticed me, or, if she had, made no account of my presence. My nerves must have been shaken by the events of the day more than I could before have believed possible: in no other way can I explain the trembling that came upon me as I watched her, and the sudden tears that half blinded my eyes. For though, no doubt, the feelings can play strange tricks in moments of crisis, and easily confound that nice order which breeding and the common proprieties impose even on our inward thoughts, it is yet notable that the perturbation that now swept my whole mind and body was without any single note or touch of those chords which can thrill so loudly at the approach of a woman of exquisite beauty and presumed accessibility. Tears of my own I had not experienced since my nursery days. Indeed, it is only by going back to nursery days that I can recall anything remotely comparable to the emotion with which I was at that moment rapt and held. And both then as a child, and now half-way down the sixties: then, as I listened on a summer’s evening in the drawing-room to my eldest sister singing at the piano what I learned to know later as Schubert’s Wohin? , and now, as I saw the Señorita Aspasia del Rio Amargo stand over my friend’s death-bed, there was neither fear in the trembling that seized me and made my body all gooseflesh, nor was it tears of grief that started in my eyes. A moment before, it is true, my mind had been feeling its way through many darknesses, while the heaviness of a great unhappiness at long friendship gone like a blown-out candleflame clogged my thoughts. But now I was as if caught by the throat and held in a state of intense awareness: a state of mind that I can find no name for, unless to call it a state of complete purity, as of awaking suddenly in the morning of time and beholding the world new born.

For a good many minutes, I think, I remained perfectly still, except for my quickened breathing and the shifting of my eyes from this part to that of the picture that was burning itself into my senses so that, I am very certain, all memories and images will fall off from me before this will suffer alteration or grow dim. Then, unsurprised as one hears in a dream, I heard a voice (that was my own voice) repeating softly that stanza in Swinburne’s great lamentable Ballad of Death :

By night there stood over against my bed

Queen Venus with a hood striped gold and black,

Both sides drawn fully back

From brows wherein the sad blood failed of red,

And temples drained of purple and full of death.

Her curled hair had the wave of sea-water

And the sea’s gold in it.

Her eyes were as a dove’s that sickeneth.

Strewn dust of gold she had shed over her,

And pearl and purple and amber on her feet.

With the last cadence I was startled awake to common things, as often, startling out of sleep, you hear words spoken in a dream echo loud beyond nature in your ears. I rose, inwardly angry with myself, with some conventional apology on the tip of my tongue, but I bit it back in time. The verses had been spoken not with my tongue but in my brain, I thought; for the look on her face assured me that she had heard nothing, or, if she had, passed it by as some remark which demanded neither comment on her part nor any explanation or apology on mine.

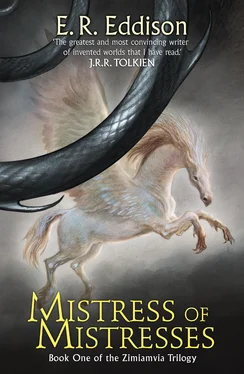

She moved a little so as to face me, her left hand hanging quiet and graceful at her side, her right resting gently on the brow of the great golden hippogriff that made the near bedpost at the foot of Lessingham’s bed. With the motion I seemed to be held once again in that contemplation of peace and power from which I had these hours past taken some comfort, and at the same time to be rapt again into that state of wide-eyed awareness in which I had a few minutes since gazed upon her and Lessingham. But now, just as (they tell us) a star of earthly density but of the size of Betelgeuze would of necessity draw to it not matter and star-dust only but the very rays of imponderable light, and suck in and swallow at last the very boundaries of space into itself, so all things condensed in her as to a point. And when she spoke, I had an odd feeling as if peace itself had spoken.

She said: ‘Is there anything new you can tell me about death, sir? Lessingham told me you are a philosopher.’

‘All I could tell you is new, Doña Aspasia,’ I answered; ‘for death is like birth: it is new every time.’

‘Does it matter, do you suppose?’ Her voice, low, smooth, luxurious (as in Spanish women it should be, to fit their beauty, yet rarely is), seemed to balance on the air like a soaring bird that tilts an almost motionless wing now this way now that, and so soars on.

‘It matters to me,’ I said. ‘And I suppose to you.’

She said a strange thing: ‘Not to me. I have no self.’ Then, ‘You,’ she said, ‘are not one of those quibbling cheap-jacks, I think, who hold out to poor mankind hopes of some metaphysical perduration (great Caesar used to stop a bung-hole) in exchange for that immortality of persons which you have whittled away to the barest improbability?’

‘No,’ answered I. ‘Because there is no wine, it is better go thirsty than lap sea-water.’

‘And the wine is past praying for? You are sure?’

‘We are sure of nothing. Every path in the maze brings you back at last to Herakleitos if you follow it fairly; yes, and beyond him: back to that philosopher who rebuked him for saying that no man may bathe twice in the same river, objecting that it was too gross an assumption to imply that he might avail to bathe once.’

‘Then what is this new thing you are to tell me?’

‘This,’ said I: ‘that I have lost a man who for forty years was my friend, and a man great and peerless in his generation. And that is death beyond common deaths.’

‘Then I see that in one river you have bathed not twice but many times,’ she said. ‘But I very well know that that is no answer.’

She fell silent, looking me steadfastly in the eye. Her eyes with their great black lashes were unlike any eyes that I have ever seen, and went strangely with her dark southern colouring and her jet-black hair: they were green, with enormous pupils, and full of fiery specks, and as the pupils dilated or narrowed the whole orbs seemed aglow with a lambent flame. Frightening eyes at the first unearthly glance of them: so much so, that I thought for an instant of old wild tales of lamias and vampires, and so of that loveliest of all love-stories and sweet ironic gospel of pagan love – Théophile Gautier’s: of her on whose unhallowed gravestone was written:

Ici gît Clarimonde,

Qui jut de son vivant

La plus belle du monde.

And then in an instant my leaping thoughts were stilled, and in awed wonderment I recognized, deep down in those strange burning eyes, sixty years in the past, my mother’s very look as she (beautiful then, but now many years dead) bent down to kiss her child good night.

The clock chiming the half hour before midnight brought back time again. She on the chime passed by me, as in a dream, and took my place in the embrasure; so that sitting at her feet I saw her side-face silhouetted against the twilight window, where the darkest hour still put on but such semblance of the true cloak of night as the dewdrops on a red rose might wear beside true tears of sorrow, or the faint memory of a long forgotten grief beside the bitterness of the passion itself. Peace distilled upon my mind like perfume from a flower. I looked across to Lessingham’s face with its Grecian profile, pallid under the flickering candles, facing upwards: the hair, short, wavy, and thick, like a Greek God’s: the ambrosial darknesses of his great black beard. He was ninety years old this year, and his hair was as black and (till a few hours ago, when he leaned back in his chair and was suddenly dead) his voice as resonant and his eyes as bright as a man’s in his prime age.

Читать дальше