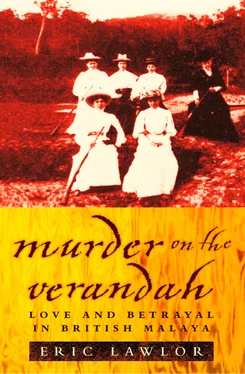

Complicating any effort to take the measure of these people is a controversy set in motion some seventy years ago by Somerset Maugham. Maugham is as much associated with Malaya as Kipling is with the British Raj but, unlike Kipling, who was born in India and spent much of his life there, Maugham visited Malaya only twice: for six months in 1921 and a further four in 1925–26. Yet out of that short acquaintance came his most enduring achievement – a group of short stories bringing Malaya so vividly to life that people named it Maugham Country.

Maugham’s portrait of Malaya’s colonials is less than flattering. The planters and officials in his stories are dull and mediocre, ‘eaten up with envy of one another and devoured by spite’. Their wives are even worse: ‘The women, poor things, were obsessed by petty rivalries. They made a circle that was more provincial than any in the smallest town in England … They were sheep.’

Cyril Connolly said of Maugham that he had done something never before achieved: ‘He tells us exactly what the British in the Far East are like.’ The British in Malaya did not agree. They said they’d been betrayed. They had taken Maugham into their homes, introduced him to their friends, made him a guest at their clubs. And for this, he had defamed them. Who are we to believe? This book is an attempt to answer that question.

One thing can be said at the outset: the British changed when they went overseas – a change that was commented on again and again. As one visitor put it: ‘Two Englishmen, one here and one at home, might easily be men of different race, language, and religion so different is their outlook and behaviour.’

In so far as it is useful, I have tried to let these people speak for themselves. This is their story after all and it seems only right that I let them help me tell it. I also draw much on the Malay Mail. With few sources at my disposal, the Mail proved a godsend. Kuala Lumpur’s only daily newspaper during this period, it is remarkable not just for the quality of its writing, but also for its knowledge of those whom it was writing about. Recruited in England, the Mail ’s editorial staff did not simply cover the British community, they formed part of it. They belonged to the same clubs, worshipped at the same church, played on the same rugby teams, shared the same beliefs. At a time when the British in KL (as Kuala Lumpur was colloquially known) numbered between seven and eight hundred, the people these journalists wrote about were, in many cases, known to them personally. I owe the Mail a debt of gratitude. Without it, my job would have been very difficult.

Before I begin, a little history. Britain, in the shape of the East India Company, acquired Penang in 1786, Malacca in 1795, and Singapore in 1819. Seven years later, the three territories were amalgamated for administrative purposes. Now called the Straits Settlements, they were ruled from India until 1867 when Penang, Malacca and Singapore became a crown colony and found themselves the responsibility of the Colonial Office.

Now the rest of Malaya beckoned. Uncharacteristically, Britain hesitated – but not out of any high-mindedness. Its reasons were practical: Westminster did not care to become embroiled in Malaya’s Byzantine politics. Besides, as long as London controlled the Straits of Malacca – crucial if it were to protect India and safeguard its trade with China – it had little need of Malaya. For years, investors in the Straits Settlements had complained to Britain that it was failing to protect their interests. They had invested large sums of money in Malaya’s tin mines, they said – money that the interminable political squabbling in that country now placed at risk. Britain ignored them.

Then the money men changed tack. If Britain would not protect them, London was warned, they would find a country that would. (Germany and Russia were mentioned as likely possibilities.) London was all ears now. The last thing it wanted was a rival in a part of the world it considered its own. And so, in 1874, the government reversed its policy, making protectorates of Perak, Selangor, Sungei Ujong (part of Negri Sembilan) and Pahang, four territories that became the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1896. Thirteen years later, Britain extended its rule again, this time to embrace the four northern states of Kelantan, Trengganu, Kedah and Perlis, long controlled by Siam. When the lone hold-out – Johore – submitted to British rule in 1914, Britain controlled the Malay peninsula as far north as the Siamese border, an area measuring 70,000 square miles. (The five newcomers declined to join the FMS and were known collectively as the Unfederated Malay States.)

In Malaya, the British employed a formula known as indirect rule, recruiting pliant elites – in this case the sultans – who became, in effect, front-men for colonial rule. The fiction put about was that the sultans, Malaya’s traditional rulers, enjoyed considerable discretion, turning to the British only when they needed help. Each state had a Resident – a senior civil servant – who was said to ‘advise’ the sultan. But no one was in any doubt as to what would happen if that advice were ever disregarded. Essentially, the sultans had a choice: they could do as they were told or be replaced by someone who would.

Because the country was never formally annexed, the British in Malaya convinced themselves that their rule owed nothing to force. This was far from being the case. True, force was rarely used, but no one in Malaya ever doubted it remained an option. When, in 1875, Malays assassinated the first Resident of Perak, the British mounted a punitive expedition that left scores of people dead.

Finally, a few words of explanation. During the period 1900 to 1910, my primary focus in this book, there were three ethnic groups in Malaya: Malays, Chinese and Indians. When referring to all three, I use the term ‘Asians’. The term ‘Malaya’ needs explaining as well. When Mrs Proudlock went on trial in 1911, Malaya comprised the Federated States, the Unfederated States and the Straits Settlements. As a single political entity, Malaya did not as yet exist. The term is convenient, however, and, as others have done, I use it here to mean that part of the Malay peninsula under British rule.

The dollar I mention from time to time is the Straits dollar which, during this period, was worth slightly less than half a crown.

I

1

‘Blood, blood. I’ve shot a man’

When she returned to her bungalow that Sunday evening, Mrs Proudlock changed from the pink dress with black spots she had worn to church to a pale-green, sleeveless tea gown with a revealing neckline. An odd choice, perhaps, for an evening of letter-writing. She chose the garment, she said later, not because it showed her to good effect, but because it was pleasantly cool. Thus arrayed, she checked to see that her daughter was sleeping (she was), fetched a blotter and an ink-stand and set to work on her correspondence.

She and her husband, William, had moved into this bungalow the previous January. Surrounded on three sides by the Klang river, it stood in the grounds of the Victoria Institution (VI), Kuala Lumpur’s premier school. Normally, B. E. Shaw, VI’s headmaster, lived here but, four months earlier, Shaw and his family had gone to England on leave. In his absence, Proudlock had been named acting headmaster, which entitled him to use Shaw’s house until the latter returned in October.

It was an attractive bungalow. Though it no longer exists – it was demolished when the Klang river, prone to flooding, was rerouted in the late 1920s – Richard Sidney, who succeeded Shaw in 1922, described it in British Malaya Today as made of wood and mounted on brick piles ‘which get higher as the ground slopes towards the river – ordinarily some 30 yards distant’. The house had its own tennis court and was fairly large, he went on. It ‘has rooms bounded by wide verandahs’. The verandah on which Mrs Proudlock wrote her letters that evening contained several of her potted plants, but most of the other furnishings belonged to Mrs Shaw: a rectangular table and some chairs arranged on a square of carpet; a long bookshelf below which was a teapoy; and a large rattan chair bearing some of Ethel’s cushions. Light was provided by a single bulb suspended from the ceiling.

Читать дальше