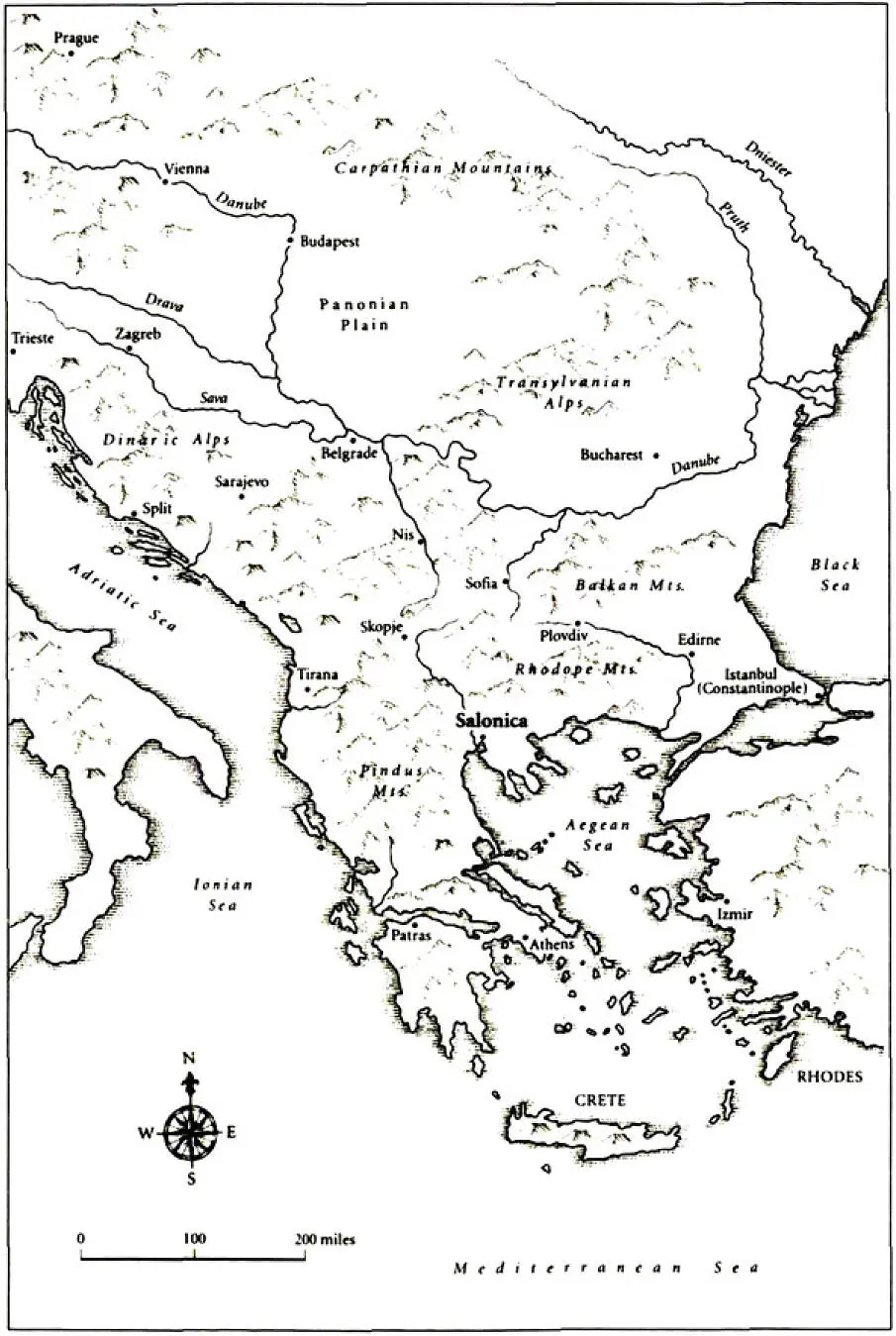

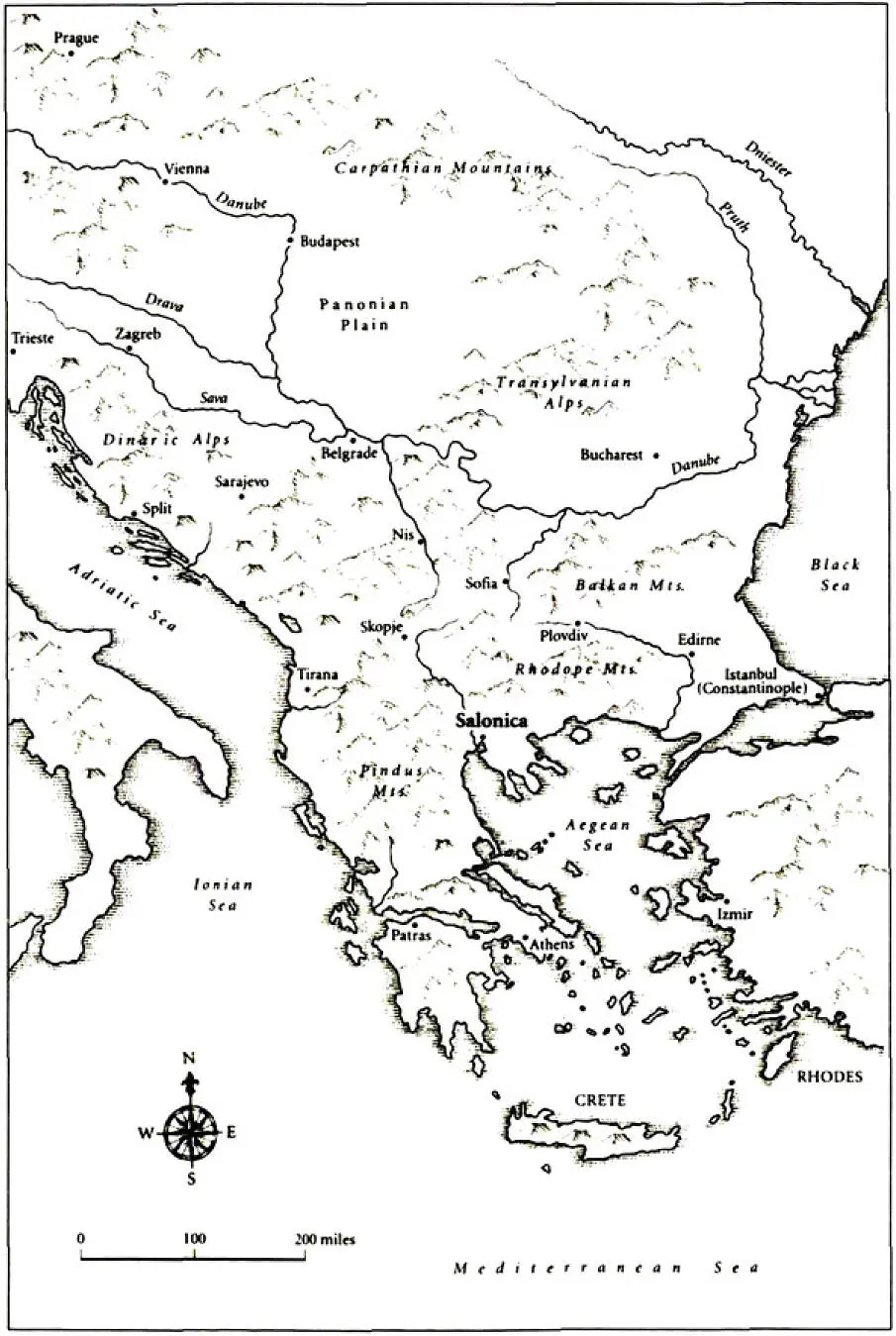

The topography of the Balkans.

Athens itself had eliminated the traces of its Ottoman past without much difficulty. For centuries it had been little more than an overgrown village so that after winning independence in 1830 Greece’s rulers found there not only the rich cultural capital invested in its ancient remains by Western philhellenism, but all the attractions of something close to a blank slate so far as the intervening epochs were concerned. Salonica’s Ottoman past, on the other hand, was a matter of living memory, for the Greek army had arrived only in 1912 and those grandmothers chatting quietly in the yards outside their homes had probably been born subjects of Sultan Abdul Hamid. The still magnificent eight-mile circuit of ancient walls embraced a densely thriving human settlement whose urban character had never been in question, a city whose history reached forward from classical antiquity uninterruptedly through the intervening centuries to our own times.

Even before one left the packed streets down near the bay and headed into the Upper Town, tiny medieval churches half-hidden below ground marked the transition from classical to Byzantine. It did not take long to discover what treasures they contained – one of the most resplendent collections of early Christian mosaics and frescoes to be found anywhere in the world, rivalling the glories of Ravenna and Istanbul. A Byzantine public bath, hidden for much of its existence under the accumulated top-soil, still functioned high in the Upper Town, near the shady overgrown garden which hid tiny Ayios Nikolaos Orfanos and its fourteenth-century painted narrative of the life of Christ. The Rotonda – a strange cylindrical Roman edifice, whose multiple re-incarnations as church, mosque, museum and art centre encapsulated the city’s endless metamorphoses – contained some of the earliest mural mosaics to be found in the eastern Mediterranean. Next to it stood an elegant pencil-thin minaret, nearly one hundred and twenty feet tall.

Like many visitors before me, I found myself particularly drawn to the Upper Town. There, hidden inside the perimeter of the old walls was a warren of precipitous alleyways sometimes ending abruptly, at others opening onto squares shaded by plane trees and cooled by fountains. One had the sense of entering an older world whose life was conducted according to different rhythms: cars found the going tougher, indeed few of them had yet mastered the cobbled slopes. Pedestrians took the steep gradients at a leisurely pace, pausing frequently for rest: despite the heat, people came to enjoy the panoramic views across the town and over the bay. Down below were the office blocks and multi-storey apartment buildings of the postwar boom. But here there were few signs of wealth. Abutting the old walls were modest whitewashed homes in brick or wood – often no more than a single small room with a privy attached: a pot of geraniums brightened the window-ledge, a rag rug bleached by the sun served as a door mat, clotheslines were stretched from house to house. Their elderly inhabitants were neatly dressed. Later I realized most had probably lived there since the 1920s, drawn from among the tens of thousands of refugees from Asia Minor who had settled in the city after the exchange of populations with Turkey. Their simple homes contrasted with the elegantly dilapidated villas whose overhanging upper floors and high garden walls still lined many streets; the majority, once grand, had been badly neglected: their gabled roofs had caved in, their shuttered bedrooms lay open to public view, and one caught spectacular glimpses of the city below through yawning gaps in their frontage. By the time I first saw them most had been abandoned for decades, for their Muslim owners had left the city when the refugees had arrived. The cypresses, firs and rosebushes in their gardens were overgrown with ivy and creeping vines, their formerly bright colours had faded into pastel shades of yellow, ochre and cream. Here were vestiges of a past that was absent from the urban landscape of southern Greece – Turkish neighbourhoods that had outlived the departure of their inhabitants; fountains with their dedicatory inscriptions intact; a dervish tomb, now shuttered and locked.

With later visits, I came to see that these traces of the Ottoman past offered a clue to Salonica’s central paradox. True, it could point, as Athens could not, to more than two thousand years of continuous urban life. But this history was decisively marked by sharp discontinuities and breaks. The few Ottoman monuments that had endured were a handful compared with what had once existed. The old houses were falling down and within a decade many of them had collapsed or been demolished. Some buildings have been recently restored and visitors can see inside the magnificent fifteenth-century Bey Hamam, the largest Ottoman baths in Greece, or admire the distinguished mansion now used as a local public library in Plateia Romfei. But otherwise the Ottoman city has vanished, exciting little comment except among preservationists and scholars.

Change is, of course, the essence of urban life and no successful city remains a museum to its own past. The expansion of the docks since the Second World War has obliterated the seaside amusement park – the Beshchinar gardens, or Park of the Princes – where the city’s inhabitants refreshed themselves for generations; today it is commemorated only in a nearby ouzeri of the same name. In the deserted sidings of the old station, prewar trams and elderly railway carriages are slowly disintegrating. Even the infamous swampy Bara – once the largest red light district in eastern Europe – survives only in the fond memories of a few ageing locals, in local belles-lettres, and in its streets – still bearing the old names, Afrodite, Bacchus – which now house nothing more exciting than car rental agencies, garages and tyre-repair shops.

But ridding the city of its brothels is one thing and eradicating the visible traces of five centuries of urban history is quite another. What, I wondered, did it do to a city’s consciousness of itself – especially to a city so proud of its past – when substantial sections were at best allowed to crumble away, at worst written out of the record? Had this happened by accident? Could one blame the great fire of 1917 that had destroyed so much of its centre? Or did the forced exchange of populations in 1923 – when more than thirty thousand Muslim refugees departed, and nearly one hundred thousand Orthodox Christians took their place – suddenly turn one city into a new one? Was the sense of urban continuity, in other words, which had so powerfully attracted me to Salonica at the outset, an illusion? Perhaps there was another urban history waiting to be written in which the story of continuity would have to be told rather differently, a tale not only of smooth transitions and adaptations, but also of violent endings and new beginnings.

For there was another vanished element of the city’s past which I was also beginning to learn about. On the drive into town from the airport, I had caught intriguing glimpses of substantial nineteenth-century villas hidden behind rusting railings and overgrown weeds amid the rows of postwar suburban apartment blocks. The palatial three-storey pile in its own pine-shaded estate, now the main seat of the Prefecture, turned out to have been originally the home of wealthy nineteenth-century Jewish industrialists, the Allatinis; this was where Sultan Abdul Hamid had been kept when he was deposed by the Young Turks and exiled to the city in 1909. Along the same road was the Villa Bianca, an opulently outsize Swiss chalet, home of the wealthy Diaz-Fernandes family. On the drive into town, one passed a dozen or more of these shrines to the eclectic taste of its fin-de-siècle elite – Turkish army officers, Greek and Bulgarian merchants, and Jewish industrialists.

Читать дальше