The court was large and populous, even when it was itinerant. Sometimes as many as 16,000 required accommodation and the chateaux of Chambord, Fontainebleau and the Louvre were constructed. Francis I was the reflective patron of the arts; Henry II became the great bibliophile of his time; and Henry IV imposed a sense of order and design on the construction of Paris, replacing the restlessness of earlier design and ornament.

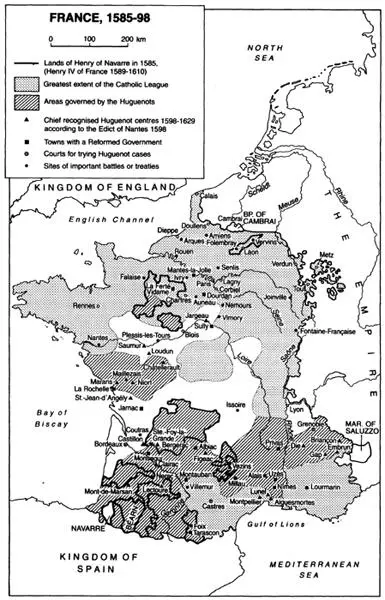

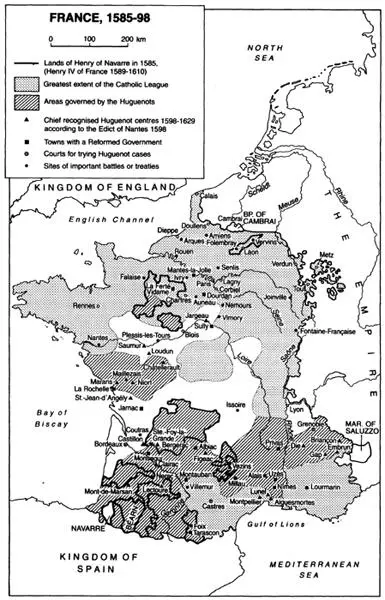

The Wars of Religion made for a dramatic revision of nationalism. France was torn apart, and even though the Protestants rallied to the royalism of Navarre and allied with their Catholic associates, the relations of church and state could never be the same again. Francis I protected the humanists – Calvin had dedicated the Latin edition of his Christian Institutes to him – but he could not tolerate those who attacked the mass.

Thus the history of Renaissance France is rich and varied. Henry IV is supposed to have said, once he had accepted the Catholic faith in 1593, ‘France and I both need time to draw breath.’ That he might well have said it is understandable. There are those students of French history who are loyal to certain individuals, such as Clovis, or St Louis or Joan of Arc. Others prefer the Age of Classicism or the Age of the Enlightenment. Still others believe that French history only began with the Revolution of 1789. But Renaissance France is perhaps the richest period in French history. We are fortunate that Professor Knecht, the biographer of Francis I and a great expert on these years, is our guide. In studying this history we are only following the precepts of Francis I himself, who in 1527 told Jacques Colin how he wished his subjects to read history books and learn from the past.

DOUGLAS JOHNSON, November 1995

A Note on Coinage and Measures

Two types of money existed side by side in sixteenth-century France: money of account and actual coin. Royal accounts were kept in the former; actual transactions carried out in the latter. The principal money of account was the livre tournois (sometimes called the franc ) which was subdivided in sous (or sols ) and deniers. One livre = 20 sous ; 1 sou = 12 deniers. This was the French equivalent of the English system of pounds, shillings and pence. The livre tournois was worth about two English shillings.

Actual coin was either gold, silver or billon: e.g. the écu au soleil was gold, the teston silver and the douzain billon. From 1500 to 1546 gold coins constituted on average two-thirds of the total annual coinage of the royal mints; thereafter till the end of the century that average fell to 17 per cent. Rulers who did not have enough coin at their disposal were naturally tempted to devalue the money of account and also to debase the precious-metal content of the coinage itself. Francis I’s successors resorted with mounting frequency to devaluation. Thus the gold écu which was valued at 40 sous in 1516, was set at 46 sous in 1550, 50 sous in 1561 and 60 sous in 1575. Over the same period, the value of the teston rose from 10 sous to 14 sous. In addition to royal coins, provincial and foreign coins circulated in France.

France had no unified system of weights and measures in the sixteenth century. Each region had its own. In Paris the setier of grain = 156 litres. Twelve setiers = 1 muid.

The title of this book requires a gloss. ‘Rise’ may be construed as a move towards political order, economic prosperity and social contentment; ‘fall’ as a lapse into political confusion, economic depression and social unrest. France in the sixteenth century experienced both conditions. This book attempts to describe and, I hope, to explain this duality in the period often called ‘the Renaissance’. Fixing the chronological limits has not been easy, for history can never be strictly compartmentalized. The division traditionally drawn between the Middle Ages and modern times is nothing more than an academic convenience; historically it makes no sense. French institutions in the sixteenth century were rooted in the Middle Ages. The significance which historians have traditionally attached to the year 1494 as ending the Middle Ages has little validity. It was then that King Charles VIII invaded Italy, setting in train a series of French wars in the peninsula which lasted on and off until the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559. I have chosen to begin my story with Charles VIII’s accession in 1483. Ideally, I should have traced the origins of the ‘rise’ back to the formative reign of Louis XI, often regarded as the founder of French national unity, but this would have lengthened the book too much. As for the ‘fall’, I might have ended with the assassination of the last Valois king in 1589. Henry IV’s reign that followed is often taken to mark the recovery of France, but there is a strong case for thinking that the real recovery did not start till 1651, after the Fronde.

In the early sixteenth century France seemed set to become the most powerful nation in Europe, yet by 1600 she had sunk to one of the lowest points in her history. Half a century of more or less continual civil conflict, allegedly over religion, had brought desolation and despair to her inhabitants. Her economy had been almost destroyed, her society was in disarray and her political system was on the brink of collapse. The very origins of a monarchy, which had once been revered as God’s lieutenancy on earth, were being questioned. Much of the interest that springs from studying sixteenth-century France resides in probing the causes of her precipitous decline. Was religion the only cause of dissension among her people, or were they responding to other factors? Why was a monarchy which had seemed so strong under Francis I and Henry II reduced to little more than an impotent figurehead? These are merely two questions among many that the reader might care to ponder. I hope to provide some answers, but the subject is vast and controversial.

The past cannot change, but history does. The last fifty years have seen considerable changes in historical thinking, particularly in France, where the Annales school has turned away from ‘the history of events’ ( histoire évènementielle ) to that of a wide-ranging interdisciplinary study of the past. This has led to a greater preoccupation with socio-economic issues, mentalités and other aspects of human activity which historians traditionally had overlooked or not seen as their concern. Recently, however, there has been a reaction. A new school of historians, less doctrinaire than their elders, have returned to the ‘history of events’ with a sharpened awareness of its complexities. The massacre of St Bartholomew’s day, for example, is no longer seen simply as the slaughter of Protestants by Catholics. The sociology of denominational violence as well as its psychological context have come under close scrutiny.

This book along with its companions in the series adheres to a chronological, not a thematic, plan, for the reader needs to be made aware of the sequence of events. However, I have tried, wherever possible, to feed analysis into the narrative, taking into account modern research. For example, the nature and effectiveness of the French monarchy has become controversial. Was it ‘absolute’, as the kings often claimed, or was it subject to limitations? The crucial importance of finance at a time when the technology of war was making unprecedented demands on the traditional resources of the state is now recognized. The French Reformation is no longer seen simply as a German import; its indigenous roots have been brought to light. We also know far more about the problems posed for the crown by the upsurge of religious dissent and about the policies by which it hoped to solve them. Religion was once dismissed as a cause of the civil wars that bear its name. It was alleged that the nobility used religion as a cover for their internecine greed. Modern research has demonstrated that religion was indeed a major source of conflict, and also an important component of popular culture, which until recently was virtually a closed book. Those pages have now been opened, and historians are better able to probe the thoughts of ordinary French men and women during the Renaissance. The psychology of denominational conflict, as reflected in a vast pamphlet literature, has been exhaustively analysed. The Wars of Religion also provided a fertile soil for political thinkers. While some upheld the doctrine of absolutism, others championed resistance to a monarchy they viewed as ungodly and therefore tyrannical. Under the cumulative impact of persecution, Protestants, who had for long adhered to the Pauline doctrine of obedience to ‘the powers that be’, turned into revolutionaries willing to condone even tyrannicide.

Читать дальше