The fact that it was the forward and not the return procession that I saw turned out to be a stroke of luck, for it enabled me to return home in time to watch most of the coronation on television. The arrival of that in the sitting room of the north London terraced house in which I grew up was another major event. But to return to the morning. That I recall as being a grey one, but then at that age just about everything I could remember had been grey, for the coronation was just eight years on from the end of the war, one which had reduced the country to penury. The capital still visibly wore the monochrome robes of that conflict, enlivened on the day by the splashes of colour of the street decorations and by the tiny red, white and blue Union flags which we clutched and waved.

It was a long wait and, as I was not tall, my chances of seeing anything were not that great. Nonetheless, there was the thrill of anticipation as a military band was heard from afar and then the great procession unfolded. I do not think that I ever saw more than the top half of a horse and rider. No matter, for two images stick in mind, ones shared at the time by millions of others. The first was an open carriage over which the capacious figure of Queen Salote of Tonga presided, beaming and waving to everyone in a manner which won all hearts. The second, of course, was the encrusted golden coach in which the Queen rode with the Duke of Edinburgh. It must have been lit from within for the Queen’s smiling features and the glitter of her diamonds remain firmly fixed in my memory.

Subsequent to that there were the pictures on the tiny television screen, hypnotic, like some dream or apparition, certainly images enough to haunt a stage-struck and historically inclined youth for the rest of his life. But I add to that the subsequent film of the coronation, for there it was on the large screen in colour, never to be forgotten, glittering, glamorous, effulgent. This was the England I fell in love with, a country proud of its great traditions and springing to life again in a pageant that seemed to inaugurate a second Elizabethan age. This was a masque of hope, a vision to uplift the mind after years of drear deprivation.

In retrospect I had seen part of what is now recognised to have been the greatest public spectacle of the twentieth century. What I was not to know was that this impoverished child in his dreary navy-blue blazer, cheap grey flannel trousers and black and gold school tie was to stand, half a century on, resplendent in scarlet and black in my role as High Bailiff and Searcher of the Sanctuary of Westminster Abbey, along with the whole college, to welcome the Queen at the great service which commemorated her coronation.

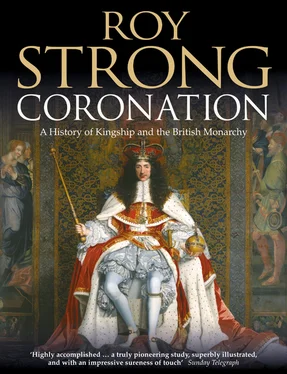

It is now all so long ago that most readers may well ask what is a coronation? Where did such an extraordinary ceremonial come from? What formed and shaped it over the centuries? And how can such a pageant ever have any relevance to the Britain of the twenty-first century? When I last visited the crown jewels in the Tower of London, part of that display was a projection of the film of the coronation. Looking at it, I could not believe that such a thing had been staged in the second half of the twentieth century and, equally, I could not help wondering whether one would ever be staged again. But then that was a viewpoint which sprang from ignorance, unaware of the rich resonances of the ritual or its deep significance in terms of the committal of the monarch to the people. It was questions like these that prompted me to write this book, launching me on a voyage that proved to be one of constant surprise. Amongst many other things it was to reveal the coronation as the perfect microcosm of a country that has always opted for evolution and not revolution. But I must begin at the beginning, and that takes us back not just centuries but no less than a thousand years.

THE EARLIEST ACCOUNT of an English Coronation comes in a life of St Oswald, Archbishop of York, by a monk of Ramsay, written about the year 1000. 1 He describes how, in the year 973, Edgar (959–75) ‘convoked all the archbishops, bishops, all great abbots and religious abbesses, all dukes, prefects and judges, and all who had claim to rank and dignity from east to west and north to south over wide lands’ to assemble in Bath. They gathered, we are told, not to expel or plot against the king ‘as the wretched Jews had once treated the kind Jesus’, but rather ‘that the most reverent bishops might bless, anoint, consecrate him, by Christ’s leave, from whom and by whom the blessed unction of highest blessing and holy religion has proceeded’. The text refers to the King as imperator, emperor, for by that date he was not only ruler of Mercia but also of Northumbria and of the West Saxons. Edgar had assumed the imperial style by 964, by which time his several kingdoms also included parts of Scandinavia and Ireland. This was a king who had come to the throne at the age of sixteen and was to die at 32. His reign was Anglo-Saxon England at its zenith, an age of peace and an era when, under the aegis of great churchmen, headed by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, a radical reform of the Church was achieved. Bath, the Roman Aquae Sulis, the place chosen for the King’s Coronation, even in the tenth century and in spite of all the barbarian depredations, would still have been a city which retained overtones of its past imperial grandeur, a setting fit for its revival by a great Saxon King.

The day chosen for the event was Pentecost, the feast of the Holy Spirit. Edgar, crowned with a rich diadem and holding a sceptre, awaited the arrival of a huge ecclesiastical procession, all in white vestments: clergy, bishops, abbots, abbesses and nuns, along with those described as aged and reverend priests. The King was led by hand to the church by two bishops, probably ones representing the northern and southern extremities of his realm, the bishops of Chester-le-Street (later to become the mighty palatine see of Durham) and of Wells. In the church the great lay magnates were already assembled. As the splendid procession wound its way from exterior secular and into interior sacred space the anthem Firmetur manus tua was sung: ‘Let thy hand be strengthened, and thy right hand be exalted, Let justice and judgement be the preparation of thy seat, and mercy and truth go before thy face.’ Here in the open air had already begun that great series of incantations to the heavens to endue this man with the virtues necessary for the right exercise of kingship.

On entering the church Edgar doffed his crown and prostrated himself before the altar while the Archbishop of Canterbury, St Dunstan, perhaps the greatest figure in the history of the Anglo-Saxon church, intoned the Te Deum, that majestic hymn of praise to God in which ‘all angels cry aloud, the heavens and all the powers therein’ and in which petition is made to ‘save thy people and bless thine heritage. Govern them and lift them up for ever.’ That prostration was an act of self-obliteration, for what was enacted before those assembled was the ‘death’ and ‘rebirth’ of a man who was to leave the church fully sanctified and endowed with grace by Holy Church as a king fit to rule. St Dunstan was so moved by the king’s action that he wept tears of joy at his humility. But such a rebirth is not bestowed without conditions, and so the great ceremonial opened with an action which was to set the English Coronation apart from any other and also account for its extraordinary longevity.

The promissio regis, the Coronation oath, consisted of what were known as the tria praecepta, three pledges by the King to God. First, ‘that the Church of God and all Christian people preserve peace at all times’, secondly, ‘that he forbid rapacity and all iniquities to all degrees’ and, finally, ‘that in all judgments he enjoin equity and mercy …’ These came in the form of a written document, whether in Latin or the vernacular is unknown, which was delivered to the King by Dunstan and then placed on the altar. The archbishop then administered the oath to the King seated. We do not know whether the oath was sworn aloud by the King to the assembled clergy and lay magnates. Logic would suggest that this happened. The placing of the tria praecepta at the opening of the Coronation service remained through the centuries one of the defining documents as to the nature of the monarchy. Monarchy in England never became, as it did in France, absolute. It always remained conditional upon being faithful to the three pledges given in the oath, to maintain peace, administer justice and exercise equity and mercy. 2

Читать дальше