In this episode we also catch something else, that it is one thing to follow a recension as it appears on the page of a pontifical and quite another to square it with what could happen on the day.

The archbishop was also the person who administered to the new king the Coronation oath, and that was to assume a place of major importance in defining the role and duties of the medieval English king. 20 The oath was not an empty ritual to be gone through, for its contents were studied both by the clerics and by the great magnates involved in the king-making process. The oath was a sacred contract administered by the archbishop with the assistance of the clergy in the presence of the lay magnates of the kingdom. In feudal society it formed the linchpin by which that society was held together. It assumed a place of even greater significance after 1066 than before it.

Although our information about the actual wording of the oaths taken by eleventh-and twelfth-century kings is scanty, there is no doubting their importance, as we have already seen in the Coronation of 1066. An account of the Coronation of Henry the Younger in 1170 describes him swearing with both his hands on the altar, on which lay not only the Gospels but relics of the saints. On that occasion, in the light of the struggle with Becket, he swore to maintain the liberty and the dignity of the Church. The oath which had begun its life under the Anglo-Saxon kings as the promissio regis, under the Normans and Angevins developed into a sacred pledge. Oaths in a feudal society were inviolate.

So the oath moved centre stage, its centrality reflected in the custom of issuing, after the Coronation, what were in effect its contents in the form of a charter. 20 The first of these came from Henry I, who had added to the second of his three promises a vow to rectify the injustices perpetrated during the reign of his brother, William Rufus. That charter, which took out to the country the pledge made in the Coronation oath, was to be evoked by successive generations as a guarantee of the rights of English men and women in respect of the crown. It was confirmed and reissued by Stephen in 1135 or 1136, by Henry II in 1154 and, most famously, in 1215 when Archbishop Stephen Langton cited it as the precedent and model for Magna Carta. The charter’s message was ‘I restore to you the law of King Edward’, that is, the Norman and Angevin kings confirmed the validity of the totality of Anglo-Saxon law as it was in the time of Edward the Confessor. 21

That oath was the obverse side of which the reverse was the act of fealty by both clerical and lay magnates. As yet it formed no part of the proceedings in church but, at this period, was a separate event enacted in the great hall of the palace when prelates and nobles rendered homage and fealty to the new ruler. Only in the case of Richard I and John do we know when this was done, in the instance of the former on the second day following the Coronation, and of the latter on the next day. 22 Much the same in terms of information applies to the Coronation feast, of which we only gain some kind of picture for that of Richard I.

During this period the Coronation was not the only occasion on which the monarch appeared crowned. 23 Circumstances could precipitate second Coronations (but not unctions), particularly on the occasion of a king marrying. In 1141 Stephen was crowned a second time at Canterbury with his wife, Matilda of Boulogne. In 1194 Richard I was crowned again on returning from the Crusade and from his years of imprisonment in Austria. In both those cases a special form of service was drawn up, initially for the crowning of 1141. The king attended by his nobles waited in his chamber for the arrival of the ecclesiastical procession. He then knelt and had the crown placed on his head by the Archbishop of Canterbury while a prayer was said. After this there was a procession to the church, during which an anthem was sung. Prayers were said and the king was led to his throne, after which a Mass was sung and the king communicated. There was a second procession back, in which the magnates carried candles, and a banquet followed.

To these rare events can be added the more regular crown-wearings at Christmas, Easter and Pentecost when the king held court. On those occasions the king and queen were escorted in a great procession to the church, where they sat crowned and enthroned. An elaborate votive Mass was sung by the archbishop during which the Laudes were chanted. Afterwards there was the usual feast, with the magnates assuming the roles of servants such as the butler or pantler or steward.

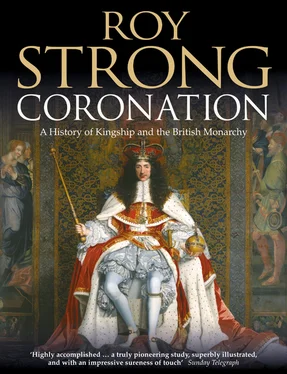

By the year 1200 the Coronation had become an essential rite of passage whereby someone was made king. That person remained Dominus Anglorum and his queen Domina Anglorum until unction was bestowed, after which they became Rex et Regina Anglorum. The transition was emphasised in the development of the procession in which the royal regalia was now carried to the church by the great nobles. That solemn transportation of crown, sceptre, orb, vestments, chalice and paten was an emphatic statement that he who walked behind them was not yet king. He became so only by a sacred initiation to be gone through at the hands of the clergy in the presence of the magnates. No document captures more vividly this huge transformation since 1066 than the description of the Coronation of Richard I in 1189.

THE CORONATION AND CHIVALRY: RICHARD I

The chronicler Roger of Wendover provides us with what is the fullest description yet of a Coronation, so much so that I quote it in full:

Then the Duke came to London, where had assembled the Archbishops, Bishops, earls and barons, and a large number of knights to meet him; and by whose advice and consent the Duke was consecrated and crowned king of England, at Westminster, on the third of September, being Sunday, the feast of the ordination of Pope St Gregory …

First came the bishops and abbots and many clerks vested in silken copes, with the cross, torch bearers, censers, and holy water going before them, up to the door of the king’s inner chamber; and there they received the said Duke Richard, who was to be crowned, and led him to the high altar of the church of Westminster with an ordered procession and triumphal chanting: and the whole way by which they went, from the door of the king’s chamber to the altar, was covered with woollen cloths.

Now the order of the procession was as follows: at the head came the clerks in vestments carrying holy water, crosses, torches and censers. Then came the priors, then the abbots; next came the bishops and in the midst of them went four barons carrying four golden candlesticks. Then came Godfrey de Lucy carrying the king’s coif, and John Marshal by him carrying two great and weighty golden spurs. Next came William Marshal, Earl of Strigul, carrying the royal sceptre, on the top of which was a golden cross, and William de Patyrick, Earl of Salisbury, by his side, bearing a golden rod with a golden dove on the top. Then came David, brother to the king of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon, and John, Earl of Moreton, brother of the Duke, and Robert, Earl of Leicester, carrying three royal swords taken from the king’s treasury, and their scabbards were wholly covered with gold: and the Earl of Moreton went in the midst. Then came six earls and barons carrying on their shoulders a very large board on which were placed the royal ensigns and vestments. Then came William de Mandeville, Earl of Albemarle, carrying a golden crown great and heavy, and adorned on all sides with precious stones. Then came Richard, Duke of Normandy, and Hugh, Bishop of Durham, went on his right hand, and Reginald, Bishop of Bath, on his left: and four barons carried over them a silken canopy on four tall lances: and the whole crowd of earls, barons, knights and others, clerk and lay, followed up to the door of the church, and they came and were brought with the Duke into the choir.

Читать дальше