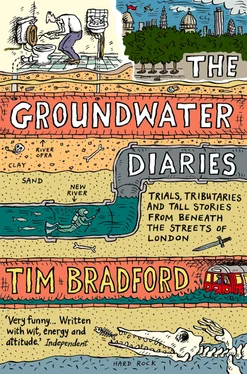

At one point Myddleton ran out of money and asked the Corporation of London for help. He was refused so turned to King James who agreed to take on half the costs (and profits). Work was finished in 1613, the river ending at an artificial pond called New River Head just off Rosebery Avenue in Clerkenwell, from where water was distributed to houses in wooden pipes. Over its 38-mile course the New River had many long twists and turns as it followed the contours of the land to maintain the steady drop from Hertfordshire to London. The New River was hailed as a great success and Myddleton became a hero. Statues of him can be seen at various stages along the river’s route.

The river travels under the road and reappears in Finsbury Park where it snakes across the ‘American Gardens’. Finsbury Park is one of the few areas in this part of north London which doesn’t seem to have had the clean-up treatment in recent years, possibly due to the fact that three borough councils – Haringey, Hackney and Islington – are responsible for different parts of it. It still has, according to official figures, a higher proportion than most parts of London of crazy nodding people, walking around talking to themselves, staring in glassy-eyed gangs outside the tube station, bumping into you and asking for money, then looking forgetful and wandering off.

One of my favourite buildings in Finsbury Park was a music venue, The George Robey, a Victorian pub which in its time had been the birth place of many third-division punk bands (though no Danish ones) is now some kind of dance club with blackened windows, a fence surround and the ubiquitous ‘security’ hanging around.

As the wooden-sided river passes the cricket pitch and under a little bridge, it’s a bizarrely rural scene, a snapshot of how the whole landscape might have looked when the river was first built. Trees hang down over the banks, the water is clear. The river winds quickly across the north side of the park then disappears under Green Lanes, in the direction of the Woodberry Down Estate, where it disappears behind a fence and railings. Woodberry Down sounds like something from Rupert Bear. By all accounts it was actually like that (not the talking animals bit) until relatively recently – photos from 100 years ago show the New River meandering gently through water meadows past trees, stationary men with big moustaches and a little country cottage. The view is still good, though, and it’s easy to imagine standing on a gentle hill looking down into a green valley of farms and rolling fields, and across Tottenham and Walthamstow marshes.

Naturally there was a danger that, people being people, the New River would soon get clogged up with all the usual debris – shit, blood, pigs’ intestines, sheep’s brains, the rotting heads of traitors, bloated corpses of drunkards who’d fallen in, everything that at that time clogged up most of the waterways of the city. The New River Company decided to combat this by building paths on each side of the river and employing walkers, big burly moustachioed men who would patrol the river and have their pictures taken when photography was invented. These walkers had the power to fine or even imprison anyone they caught throwing rubbish or simply pissing into the river.

By the mid-nineteenth century most of the water supplies in London were once again polluted. The cholera epidemic of 1849 would eventually be traced to the contaminated water supply at Broad Street in Soho. Thanks to the New River Company’s vigilance, their water remained pure and drinkable but as a result it was too expensive for the poor of London. The philanthropist Samuel Gurney spotted a gap in the charity market and under the auspices of his new and snappily named the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association, opened London’s first drinking fountain in Snow Hill, from water pumped (and bought) from the New River.

I cut across past Manor House, named after the old manor of Stoke Newington which stood nearby. Manor House is a big strippers’ and showbands’ pub, or at least it would have been in its glory days. I walk along the rumbling and dusty Seven Sisters Road for a quarter of a mile until the New River appears on my left looking very sad, chained up, covered in green American algae, another of those crap Stateside imports up there with grey squirrels and confessional TV, with a shopping trolley and plastic football set fast in the gunge. At Sluice House Nine (Kurt Vonnegut’s London novel), on Newnton Close, in the shadow of three big tower blocks, I am finally able to get back down to the river and walk alongside it as it winds past the East Reservoir, still covered in algae scum. There’s a sense of boundary here between the self-conscious bourgeois charm of Stoke Newington to the south – with the reservoir and trees, a church spire, Victorian rooftops, it could be the countryside – and the more uncontrolled and more recently built-up area around Seven Sisters Road to the right, a canvas of white council slab flats, shopping trolleys left upturned, kids playing football (two kids are trying to juggle a ball then the smaller of the two nicks it off the big one. The big kid knocks him over), an old people’s haven with three plastic benches like a prison. These tower blocks, another part of the huge Woodberry Down Estate, are quite spectacular.

The scheme had originally been planned in the early twenties when it was decided to get rid of much of the Victorian architecture in the area (Victorians hated Georgians, Modernists hated Victorians, we hate the Modernists – those fucking bastards), although not finished until 1952. Its four eight-storey slab blocks with projecting flat roofs in parallel rows were designed in a ‘progressive Scandinavian style coloured in the pale cream like Swiss municipal architecture’ according to the bloke in the little Turkish grocer’s shop across the way on Lordship Road.

The reservoir is a haven for birds and their human sidekicks, birdwatchers. Looking back, where the river meets the road, is my favourite view of the New River – a blanket of green covers a small sluiced section dotted with cans, blue girders, a red plastic football, aerosols and bottles coming up for air like gasping fish, the three identical tower blocks of Stamford Hill rising in the distance like silver standing stones. There’s ducks too, one old lad with four duck chicks – well, not chicks, they’re ducks, and one younger male with a dodgy leg who’s just been beaten up, probably in a fight over the duck harem, which waits in the background ready to change allegiance at a moment’s notice should the old fella peg it suddenly.

Across the road on Spring Park Drive is a fifties estate. A fat woman shouts out of a sixth-storey window to her daughter below, ‘Oi, get me some leeks.’

‘I don’t want to get leeks,’ says the girl.

‘Get me some fucking leeks, you little bitch,’ shouts her mum.

‘I don’t want to,’ says the girl and the mother is looking very, very angry. Get the leeks, go on, for a quiet life.

‘I don’t know what leeks look like anyway,’ the girl shouts up, then runs away. A right turn and there’s an old wooden bench on a patch of grass that once would have had old lads sitting down looking over the view, now it just looks onto the health centre. Look, there’s the window where they had the wart clinic. Ah, those were the days. Across Green Lanes again into the back streets and onto Wilberforce Road, with its rows of massive Victorian houses where there are always big puddles on the tarmac. Only 150 years ago all this area north of here up to Seven Sisters Road was open countryside with two big pubs, the Eel Pie House and the Highbury Sluice alongside the river, where anglers and holidaymakers would hang out. Then, in the 1860s, the pubs were pulled down and everything built over in a mad frenzy. If you compare an 1850s map of the district and the 1871 census map you can see the rapid growth of residential streets in Highbury and south Finsbury Park.

Читать дальше