At around the same time Charles read two books that ‘stirred up in me a burning zeal to add even the most humble contribution to the noble structure of Natural Science’. One was the classical account by the German naturalist, geophysicist, meteorologist and geographer Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) about his travels through the Brazilian rain forest to the Andes and beyond with the botanist Aimé Bonpland (1773–1858). 26 The second was the recent book by the astronomer and physicist John Herschel (1792–1871) on the study of natural science. 27 Charles insisted on inflicting long readings from Humboldt on his friends, and worked out plans for an expedition to the Canary Islands in July to inspect the volcanic cone of the Pico de Teide on Tenerife, whose summit had been closely inspected by Humboldt in 1799 on his way out to South America. Some of the requirements of his plan were tiresome to meet, such as taking ‘intensely stupid’ lessons in Spanish, though he was not to know how useful they would prove to have been when later on he was riding with gauchos across the pampas in Patagonia. A number of prospective participants were enlisted, but on enquiring about the sailing of passenger vessels to the Canaries, Charles found that his planning was already too late, for the boats were scheduled for departures only in June. The trip would therefore have to be postponed to 1832.

It was pointed out by Henslow that such an enterprise would require a basic knowledge of geology. He therefore advised Charles on the purchase in London of the instrument for the measurement of the inclination of rock beds known as a clinometer, and showed him how to use it. Soon Charles could boast from Shrewsbury that ‘I put all the tables in my bedroom at every conceivable angle & direction. I will venture to say I have measured them as accurately as any Geologist going could do.’ 28

Most significantly of all for Charles’s training as a geologist, Henslow prevailed on Adam Sedgwick to take Charles with him for part of his usual field excursion during the summer vacation. Sedgwick was renowned as a field geologist, skilled at the recognition of regional patterns of strata from details that were strictly local, and in August he was planning to visit North Wales in continuation of a project to describe all the rocks in Great Britain below the Old Red Sandstone. * The first nights of the trip were spent by Sedgwick with the Darwins at Shrewsbury, where he made a great impression, especially on Charles’s sister Susan, often teased by the accusation that ‘anything in coat and trousers from eight years to eighty was fair game to Susan’. Charles had been practising his geology in the neighbourhood, and later related the story of the important scientific lesson that he learnt on that occasion:

Whilst examining an old gravel-pit near Shrewsbury a labourer told me that he had found in it a large worn tropical Volute shell, such as may be seen on the chimney-pieces of cottages; and as he would not sell the shell I was convinced that he had really found it in the pit. I told Sedgwick of the fact, and he at once said (no doubt truly) that it must have been thrown away by someone into the pit; but then added, if really embedded there it would be the greatest misfortune to geology, as it would overthrow all that we know about the superficial deposits of the midland counties. These gravel-beds belonged in fact to the glacial period, and in after years I found in them broken arctic shells. But I was then utterly astonished at Sedgwick not being delighted at so wonderful a fact as a tropical shell being found near the surface in the middle of England. Nothing before had ever made me thoroughly realise, though I had read various scientific books, that science consists in grouping facts so that general laws or conclusions may be drawn from them. 29

Sedgwick had of course appreciated that the shell could not possibly be a genuine find in such a place. His scepticism taught Charles a valuable lesson, and brought home to him the importance of assembling plenty of mutually compatible observations to support any new scientific theory. Thereafter he would keep his mouth tightly shut until sufficient evidence had been accumulated.

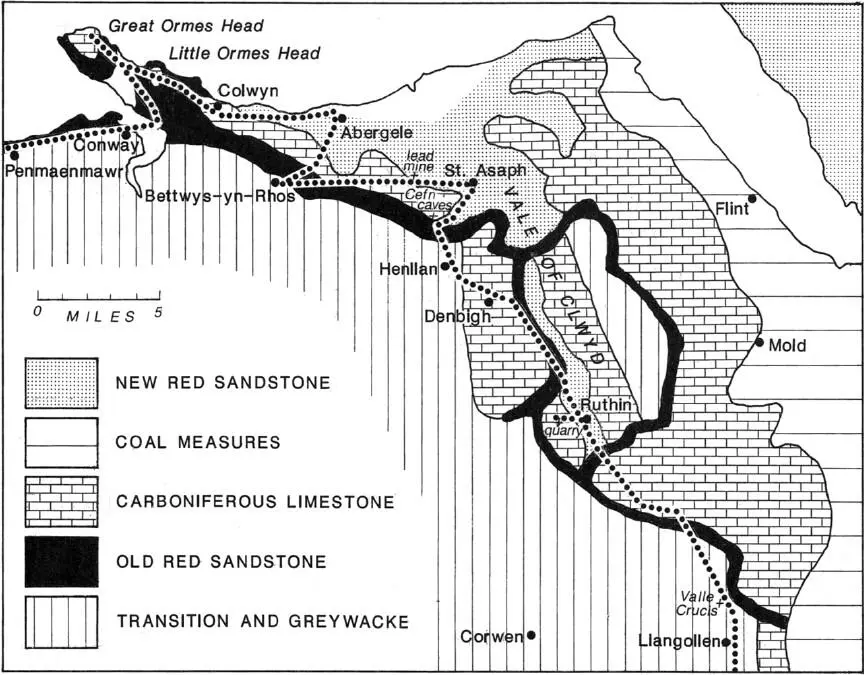

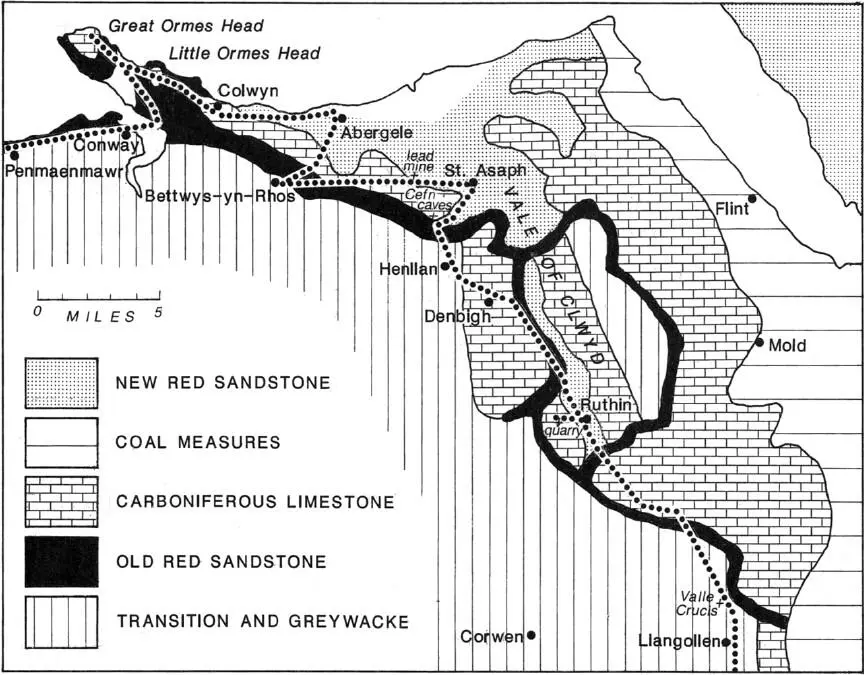

Sedgwick’s aim was to follow the line of contact along the Vale of Clwyd between the Carboniferous Limestone cliffs and the Old Red Sandstone, shown in the geological map with ribbons crossing the Vale at several points, starting at Llangollen and finishing at Great Ormes Head on the coast. 30 At a quarry near Ruthin they found a possible outcrop of the Old Red, and north of Henllan there was red sand and earth, but Sedgwick was not sure that this established with certainty the nature of the underlying strata. Charles was therefore dispatched on a traverse of his own from St Asaph to Abergele via Betwys-yn-Rhos, crossing a substantial band of Old Red shown on the map. Finding in some places a few loose stones and some reddish soil, he noted: ‘It was in such points as these where the strata have been much disturbed, that I observed the greatest number of bits of Sandstone, but in no place could I find it in situ.’ 31 Near Abergele the soil was indeed ‘very red’, but this he attributed ‘entirely to the very ferruginous [rich in iron] seams in the rock itself, & not to the supposed sandstone beneath it’. That evening he told Sedgwick that there was no true Old Red to be seen, and to the end of his life could remember how pleased his teacher had been with this new evidence that the Vale of Clwyd did not have a complex structure as had been supposed, but was a simple trough-like syncline * resulting from a stretching of the strata. Although his experience of geology in the field was thus limited to just one week, Charles had sat at the feet of a master, and had solved his first problem with conspicuous success.

Geological map of part of North Wales, redrawn by Secord 15 after Greenough, 30 with Charles’s route from Llangollen to Penmaenmawr as a dotted line. In the second edition of Greenough’s map, published in 1839, the Old Red Sandstone had disappeared.

Among other sites of geological interest in the Vale were the famous caves in the limestone cliffs at Plas-yn-Cefn, above the River Elwy. Here the owner had excavated vertebrate fossils in the largest cave that included the tooth of a rhinoceros, and there were other bones in the mud. Charles’s imagination was fired by the prospect of making similar discoveries from past worlds in his projected trip to the Canaries, though his hopes were not in fact realised until his arrival in 1832 at the cliffs of Punta Alta in Patagonia. After a week, Charles and Sedgwick separated at Capel Curig in the neighbourhood of Bethesda, and Charles strode on across the central mountains of Wales, steering by map and compass, to join some Cambridge friends at Barmouth.

Reaching home at Shrewsbury on 29 August 1831 after two weeks of shooting with his Uncle Jos at Maer, ‘for at that time I should have thought myself mad to give up the first days of partridge shooting for geology or any other science’, Charles found the fateful letter from Henslow proposing that he should sail on the Beagle . The clock must next be turned back to explain its origin.

CHAPTER 2

The Strange Consequences of Stealing a Whale-Boat

On 25 September 1513 the Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the narrow isthmus joining the two halves of the American continent to discover on the far side the Mar del Sur, later named the Pacific Ocean. The town of Panama was built on the Pacific shore, and became the base for a rapid expansion by the Spaniards. While Hernán Cortés was conquering the Aztec empire in Mexico, Francisco Pizarro was overcoming the Incas in Peru. During the next three hundred years prosperous Spanish colonies were established in the western and southernmost parts of South America, while in the east the Portuguese took over a large area in Brazil.

Читать дальше