They had rambled as far as a large seventeenth- and eighteenth-century house, Alfoxden, hipped roof, wide cornice, far-gazing windows, in a large park, with seventy head of deer grazing and browsing around it. The sequestered waterfall was in the dell or combe or glen that formed the eastern boundary of the park, with the village of Holford on the far side. It turned out that the house was for rent – its owner, a St Albyn, was a minor, away as an undergraduate at Balliol College, Oxford, and the Wordsworths could have it for £23 a year, taxes included. Tom Poole made the arrangements, and the lease was signed.

‘The house is a large mansion, with furniture enough for a dozen families like ours,’ Dorothy told her childhood friend Mary Hutchinson.

There is a very excellent garden, well stocked with vegetables and fruit. The garden is at the end of the house, and our favourite parlour, as at Racedown, looks that way. In front is a little court, with grass plot, gravel walk, and shrubs; the moss roses were in full beauty a month ago. The front of the house is to the south, but it is screened from the sun by a high hill which rises immediately from it. This hill is beautiful, scattered irregularly and abundantly with trees, and topped with fern, which spreads a considerable way down it. The deer dwell here, and sheep, so that we have a living prospect. From the end of the house we have a view of the sea, over a woody meadow-country; and exactly opposite the window where I now sit is an immense wood, whose round top from this point has exactly the appearance of a mighty dome. In some parts of this wood there is an under grove of hollies which are now very beautiful. In a glen at the bottom of the wood is the waterfall of which I spoke, a quarter of a mile from the house. We are three miles from Stowey, and not two miles from the sea. Wherever we turn we have woods, smooth downs, and valleys with small brooks running down them through green meadows, hardly ever intersected with hedgerows, but scattered over with trees. The hills that cradle these valleys are either covered with fern and bilberries, or oak woods, which are cut for charcoal … Walks extend for miles over the hill tops, the great beauty of which is their wild simplicity: they are perfectly smooth, without rocks. The Tor of Glastonbury is before our eyes during more than half of our walk to Stowey; and in the park wherever we go … it makes a part of our prospect …

Somehow the Wordsworths had brought their gentlemanliness with them, and had stumbled on a handsome pedimented house, filled with old hangings and ‘covered with the round-faced family portraits of the age of George I and II’, not unlike and actually larger than Racedown, with hints of Lonsdale grandeur. The way in which Dorothy described it to her friend feels nearly like an heiress coming into her own. Her language is virtually without the stock Romantic or even pre-Romantic phrases that would have displayed the fashionable attitudes to place. The only hint in these letters that she is not a straightforward member of the landowning classes is her love of the ‘wild simplicity’ of the hill tops. Otherwise it is a land surveyor’s account, allied to a calm and proprietorial description of an elegant landscape seen as the declaration of a well-ordered life and a contented household. The much-admired, sparkle-eyed observer of the slivers and specks of the natural world, the empathiser with the poor and troubled, the poet of the unnoticed and the everyday, seems to have slipped away here under the manners and modes of the gentleman and the squire.

Perhaps one can see in this the Dorothy who was the source of strength and connection in their lives, who sustained her broken brother, the irrigating woman-brook, ‘seen, heard, felt, and caught at every turn’. Audible in that account is ‘the voice of sudden admonition’ with which she recalled Wordsworth to his ‘office upon earth’, his destiny as a poet. Its authority is unmistakable. None of this was coming from Wordsworth himself, and in the months that followed, that ownership of settled beauty was the very opposite of what Wordsworth himself would find here.

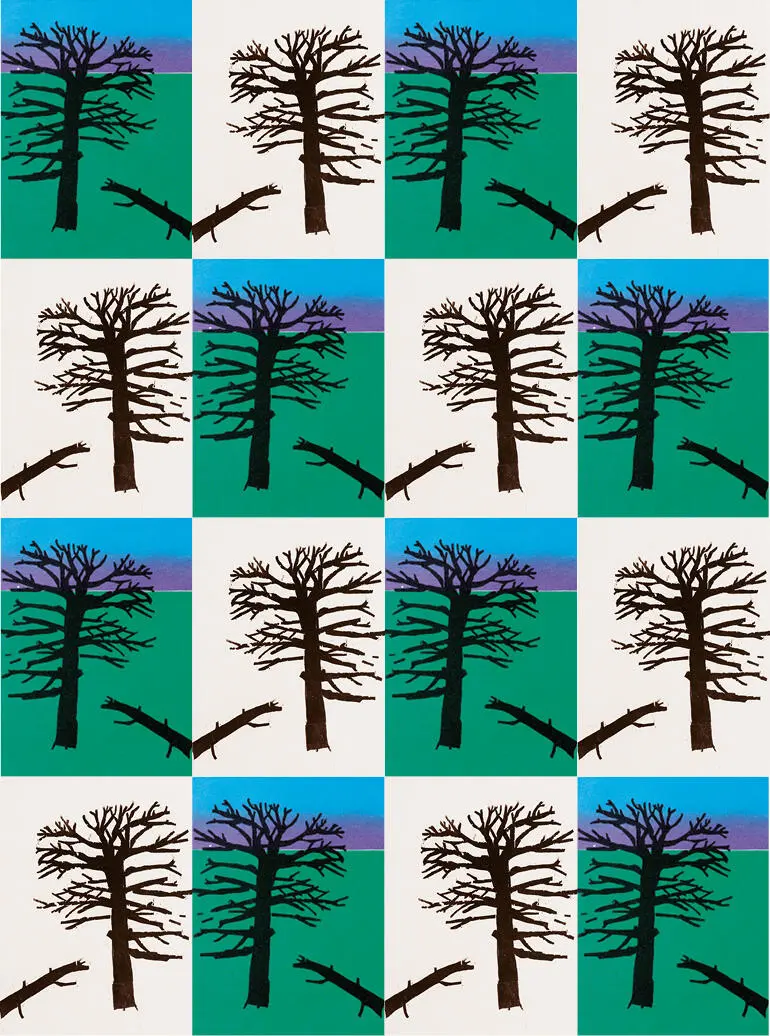

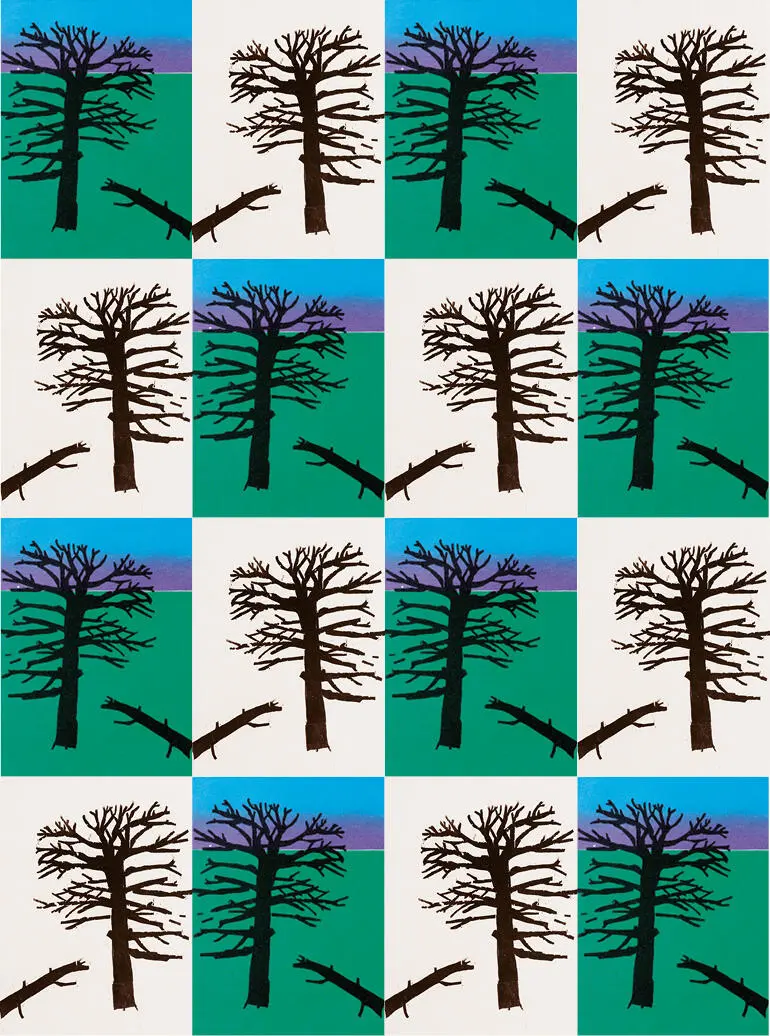

Alfoxden – called by Coleridge ‘All the Foxes Den’ and by most people, dully, Alfoxton – remains a beautiful and haunting place. The house is now decrepit, and the park broken and ragged. It is scarcely visited. Unlike Coleridge’s spruced-up cottage in Nether Stowey, no National Trust care is applied to the flaking and rotting surfaces of these buildings. Little wrens play on the cornices and pied wagtails pick through the gravel where the moss roses used to flower. The roof in places is breaking through, and the paint on the doors looks as if it has been peppered with gunshot. The walled garden is abandoned, and the trees lie collapsed and broken where they have fallen, vast twisted and spiralled chestnuts lying riven on the hillside, as if a war had been fought through them.

Broken Park

That very condition, on a thick summer evening, with the leaves darkening in the dusk, the bats flicking and scouting overhead, and the deer rustling their anxious, hidden bodies somewhere up in the bracken, has over the centuries absorbed, ironically enough, a Wordsworthian atmosphere. Now Alfoxden seems more than ever like his place, with an ancient grandeur, poised and beautifully placed between hill and sea, with its own apron of hedge and field spread out in front of it towards the grey waters of the Bristol Channel to the north. Everywhere the atmosphere is of decay and breakage, as if forgotten, a fraying cloth, a place shut up and shuttered, ragwort on the lawns and marsh thistles in ranks in front of the house like ushers at its death. On the upper edges of the park the rim of beech trees stands waiting for the old beast to lie down.

Allow night to fall here, and memory and hauntedness come easing out of the ground, a dusk in which Alfoxden’s half-ruin summons the sense of marginal understanding, of something growing in significance because only half-seen, which is one of Wordsworth’s lasting gifts to the world. It is easy to imagine that he was like this himself in these years, a man glimpsed but never quite grasped, always a suggestion of a resolution in him, making half-gestures, a raised eyebrow, an almost-smile, so that his whole being appeared more latent than present.

His repeated habit in poetry, and perhaps in speech, was to use the double negative. Pleasures were not unwelcome, sounds not unheard, understandings not ungrasped. Even when he feels, for instance, the ‘mild creative breeze’ lifting within him, the very centre of his being as a poet, he calls it ‘a power/that does not come unrecognised’.

Everything hangs there as a suggestion. The wind of poetry is no more than a breath of stirring air, and Wordsworth only half-knows it for what it is. That half-state, a not-unreality, is the condition of his inner life, his duskiness, and now, through neglect, is the very state that Alfoxden has come to. There are no mathematics here; the two negatives do not cancel each other out, or at least in their mutual cancelling leave the ghost of a third term, something which might have been or might yet be. The mild creative breeze is itself an aspect of the tentative, a half-feeling, a stirring of the inner atmosphere that might or might not be the making of poetry. There is no certainty that it is; nor any that it is not. That very hanging in a qualified neutrality, which smells of something and suggests something but isn’t quite the thing itself, is the revelatory thing. It is the simmering of a presence, not the memory of a presence but the promise of a presence which bears the same relationship to the future as a memory does to the past.

Читать дальше