The atmosphere in those days was tense and uncertain – the rumour mill was in overdrive about what might happen next. At the top, Erich Honecker envisaged a ‘Chinese solution’ to counter the mounting protests over the anniversary weekend (6–9 October), [20]prefigured in East Berlin when Stasi boss Erich Mielke jumped out of his bulletproof limo on the evening of 7 October screaming to police ‘ Haut sie doch zusammen , die Schweine! ’ (‘Club those pigs into submission!’). [21]That night in and around Prenzlauer Berg near the Gethsemane church, police officers, plain-clothes security forces and volunteer militia attacked some 6,000 demonstrators who shouted ‘Freedom’, ‘No violence’ and ‘We want to stay’, as well as bystanders, with dogs and water cannons – beating and kicking peaceful citizens and throwing hundreds into jail. Women and girls were stripped naked; people were not allowed to use the toilets and told to piss or shit in their pants. Those who asked where they would be taken were told: ‘ Auf eine Müllkippe ’ (‘To the landfill’). [22]

Unlike similar scenes in other East German cities, where foreign journalists were banned, the images from East Berlin that weekend soon went around the world. And when those arrested were released and talked to the press, what they told the cameras about merciless brutality by the riot police and abuse at the hands of the Stasi interrogators was both really shocking and also entirely believable. Because many of them were simply ordinary citizens, some even SED members, not militant protestors or hardcore dissidents. [23]

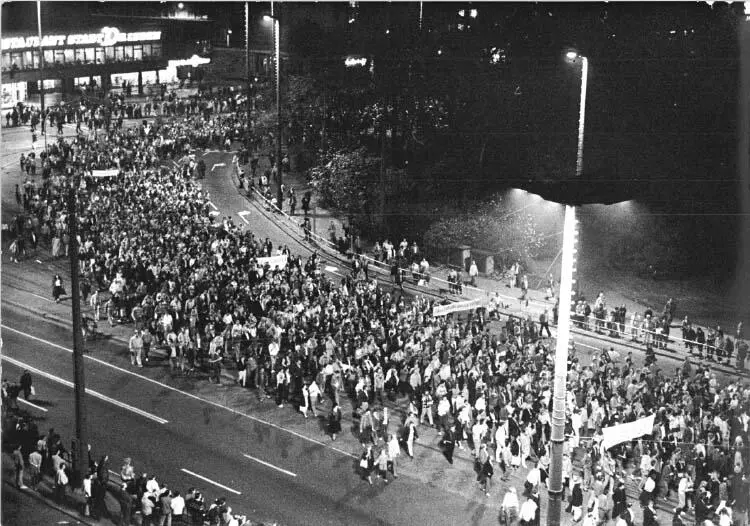

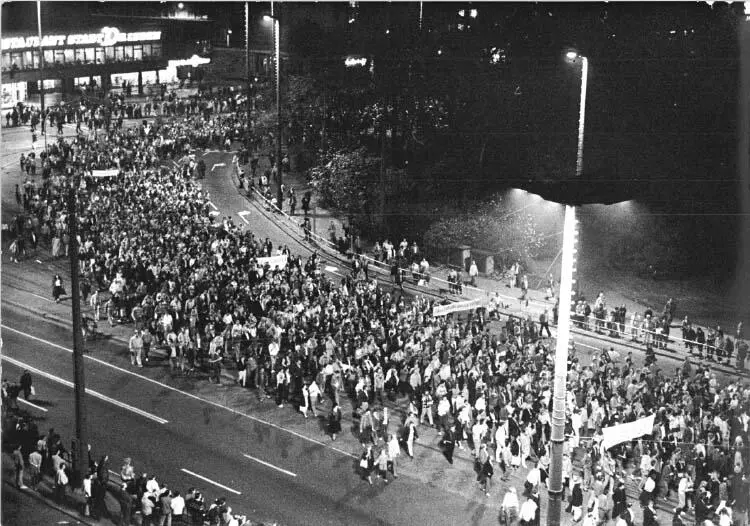

Matters came to a head on Monday 9 October in Leipzig, which had been the epicentre of people-protest for the past few weeks. In fact the Monday night demo there had become a weekly feature since the first gathering by a few hundred in early September, spilling out spontaneously – as numbers grew exponentially – from the evening prayers for peace ( Friedensgebet ) in the Nikolaikirche in the city centre to a big rally along the inner ring road. On the night of 25 September, the fourth such occasion, 5,000 people had come together; a week later there were already 15,000, calling for ‘ Demokratie – jetzt oder nie ’ (‘Democracy – now or never’), and ‘ Freiheit, Gleichheit, Brüderlichkeit ’ (‘Freedom, equality, fraternity’). On the march, they chanted defiantly ‘ Wir bleiben hier ’ (‘We stay here’), as opposed to the earlier ‘ Wir wollen raus ’ (‘We want out’), while demanding ‘ Erich laß die Faxen sein, laß die Perestroika rein ’ (‘Erich [Honecker] stop fooling around, let the perestroika in’). Each week, Leipzigers became more daring in their activities and more vehement in their demands. [24]

The 9th of October was expected to be the largest ever protest – facing off against the regime’s full display of force. With this in mind, the Leipzig opposition groups and churches had disseminated appeals for prudence and non-violence. The world-renowned conductor Kurt Masur of the Gewandhaus orchestra, together with two other local celebrities, enlisted the support of three leading SED functionaries of the city government, and issued a public call for peaceful action: ‘We all need free dialogue and exchanges of views about further development of socialism in our country.’ What’s more, they argued, dialogue should not only be conducted in Leipzig but also with the government in East Berlin. This so-called ‘Appeal of the Six’ was read aloud, as well as being broadcast via loudspeakers across the city during the evening church vigils. [25]

Honecker, for his part, was determined to make an example of Leipzig. The state media replayed footage of Tiananmen and endlessly repeated the government’s solidarity with their comrades in Beijing. [26]When Honecker met Yao Yilin, China’s deputy premier, on the morning of the 9th, the two men announced that there was ‘evidence of a particularly anti-socialist action by imperialist class opponents with the aim of reversing socialist development. In this respect there is a fundamental lesson to be learned from the counter-revolutionary unrest in Beijing and the present campaign’ in East Germany. Honecker himself was positively bombastic: ‘Any attempt by imperialism to destabilise socialist construction or slander its achievements is now and in the future nothing more than Don Quixote’s futile running against the steadily turning sails of a windmill.’ [27]

As darkness fell that evening, 9 October, with memories fresh of horrors from Berlin, many expected a total bloodbath in Leipzig. Honecker had pontificated that riots should be ‘choked off in advance’. Some 1,500 soldiers, 3,000 police and 600 paramilitary backed by hundreds of Stasi agents were ready. ‘It is either them or us,’ police were told by their superiors. ‘Fight them with no compromises,’ the interior minister ordered. The army had been given live ammunition and gas masks; the Stasi were briefed by Mielke in person; and paramilitaries and police were also called up in readiness. [28]Around 6 p.m., after prayers at the Nikolaikirche and neighbouring churches, the crowd struggled out into the streets. With more people joining the march all the time, an estimated 70,000 slowly pushed their way out onto the ring road. [29]

Marching for democracy on the Leipziger Innenstadtring

Yet the dreaded confrontation never took place. The local party was unwilling to make a move without detailed instructions from the leadership in East Berlin. The army and police were not prepared for the size of the crowd, double what they had expected. Above all, Honecker’s word was no longer law. An intense power struggle was now under way in East Berlin. Egon Krenz – twenty-five years Honecker’s junior – had been plotting a coup for some time. But, despite his recent ‘fraternal’ visit to Beijing, he did not wish to be saddled by Honecker with the opprobrium of a Tiananmen solution at home, because that would stain his own hands with German blood while allowing the elderly leader to blame him for the violence. This left the party paralysed between hardliners, ditherers and reformers. And, with no clear word that night from Berlin, the local party chief did a volte-face. Heeding the Appeal of the Six, he ordered his men to act only in self-defence. Meanwhile, the Kremlin had issued a directive to General Boris Snetkov, commander of the Western Group of Soviet Forces with his HQ in Wünsdorf near Berlin, not to intervene in East German events. The Red Army troops on East German soil were to stay in their garrisons.

So the ‘Chinese card’ was never played. Not because of a deliberate decision by the SED at the top, growing out of a change of heart, but because of the distinct absence of any decision. Time passed. The masses kept marching. There was no violence. The repressive state apparatus that Mielke had pulled together was not confronted with fearsome ‘enemies of the state’ or anarchic ‘rowdies’ but by well-disciplined ordinary citizens bearing candles and speaking the language of non-violence. What they wanted was recognition by the governing party of their legitimate quest for basic freedoms and political reform: their slogan was ‘ Wir sind das Volk ’ (‘We are the people’). [30]

New facts on the ground had been created. And a new demonstration culture had emerged – spilling out from the church vigils into the squares and the streets. The regime’s loss of nerve that night dispelled the omnipresent climate of fear. This would change the face of the GDR. The civil rights activists and the mass of protestors were beginning to merge.

Читать дальше