Homer B. Hulbert - The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Homer B. Hulbert - The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The History of Korea (Vol.1&2): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The History of Korea (Vol.1&2) — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The retreating forces of Kitan were again engaged at A-jin but as heavy reinforcements arrived at the moment, the Koryŭ generals, Yang Kyu and Kim Suk-heng, lost the day and fell upon the field of battle. This victory, however, did not stop the retreat of the invading army. There had been very heavy rains, and many horses had perished and many soldiers were practically without arms. Gen. Chon Song, who assumed command after the death of the two generals at K-jŭn, hung on the flanks of the retreating enemy and when half of them had crossed the Yalu he fell upon the remainder and many of them were cut down and many more were drowned in mid-stream. When it became known that all the Kitan forces were across the border it took but a few days to re-man the fortresses which had been deserted.

The king now hastened northward stopping for a time at Kong-ju where the governor gave him his three daughters to wife. By the first he begat two sons both of whom became kings of Koryŭ, and by the second he begat another who also became king. He was soon on the road again, and ere long he reentered the gates of his capital which had undergone much hardship during his absence. His first act was to give presents to all the generals and to order that all the bones of the soldiers who had fallen be interred. He followed this up by dispatching an envoy to the Kitan thanking them for recalling their troops. He banished the governor of Chŭn-ju who had attempted his life. He repaired the wall of the capital and rebuilt the palace.

Gen. Ha was still in the hands of the Kitan but he was extremely anxious to return to Koryŭ. He therefore feigned to be quite satisfied there and gradually gained the entire confidence of his captors. When he deemed that it was safe he proposed that he be sent back to Koryŭ to spy out the condition of the land and report on the number of soldiers. The emperor consented but changed his mind when he heard that the king had returned to Song-do. Instead of sending Gen. Ha back to Koryŭ he sent him to Yun-gyŭng to live and gave him a woman of high position as his wife. Even then the general did not give up hope of escaping and was soon busy on a new plan. He purchased fleet horses and had them placed at stated intervals along the road toward Koryŭ with trusty grooms in charge of each. Someone, however, told the emperor of this and, calling the exile, he questioned him about it. Gen. Ha confessed that his life in exile was intolerable. When the emperor had offered him every inducement to transfer his allegience and all to no avail, he commandedto no avail, he commanded the executioner to put an end to the interview. When news reached Song-do that Gen. Ha had preferred death to disloyalty, the king hastened to give office to the patriot’s son.

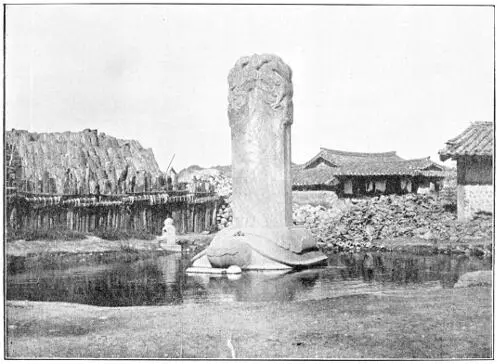

A BUDDHIST MONUMENT (EIGHT HUNDRED YEARS OLD).

The work of reconstruction was now commenced, in 1012. Kyöng-ju was no longer called the eastern capital but was changed back to a mere prefecture. The twelve

The twelve provinces were reconstructed into five and there were seventy-five prefectures in all. This plan however was abandoned two years later. Now that Koryŭ had regained control of her own territory, the Yŭ-jin tribe thought best to cultivate her good will and so sent frequent envoys with gifts of horses and other valuables. But when the Emperor of Kitan, angry because the King refused on the plea of ill health to go to Kitan and do obeisance, sent an army and seized six of the northern districts this side the Yalu, the Yŭ-jin turned about and ravaged the northeast boundary. The next year the Yŭ-jin joined Kitan and crossed the Yalu but were speedily driven back by Gen. Kim Sang-wi.

In 1014 the King came to the conclusion that he had made a mistake in casting off the friendship of China and sent an envoy to make explanations; but the Emperor Chin-jong (Sang dynasty) was angry because he had been so long neglected and would have nothing to do with the repentant Koryŭ.

In the autumn the Kitan army was again forced back across the border. The Koryŭ army had now grown to such proportions that the question of revenue became a very serious one and the officials found it necessary to suggest a change. They had been accustomed to “squeeze” a good proportion of the soldiers’ pay and now that there was danger of further change which would be only in the officials’ favor, the soldiers raised a disturbance, forced the palace gates, killed two of the leading officials and compelled the King to banish others. They saw to it that the military officials took precedence of civil officials. From that time on there was great friction between the military and civil factions, each trying to drive the other to the wall.

The next year, 1015, the Kitan people bridged the Yalu, built a wall at each end and successfully defended it from capture; but when they attempted to harry the adjoining country they were speedily driven back. The military faction had now obtained complete control at the capital. Swarms of incompetent men were foisted into office and things were going from bad to worse. The King was much dissatisfied at this condition of affairs and at some-one’s advice decided to sever the knot which he could not untie. He summoned all the leaders of the military faction to a great feast, and, when he had gotten them all intoxicated, had them cut down by men who had lain concealed in an adjoining chamber. In this way nineteen men were put out of the way and the military faction was driven to the wall.

Year by year the northern people tried to make headway against Koryŭ. The Sung dynasty was again and again appealed to but without success. Koryŭ was advised to make peace with Kitan on the best terms possible. The Kitan generals, Yu Pyul, Hăng Byŭn and Ya-yul Se-chang made raid after raid into Koryŭ territory with varying success. In 1016 Kitan scored a decisive victory at Kwak-ju where the Koryŭ forces were cut to pieces. Winter however sent them back to their northern haunts. The next year they came again and in the following year, 1018, Gen. So Son-ryŭng came with 100,000 men. The Koryŭ army was by this time in good order again and showed an aggregate of 200,000 men. They were led by General Kang Kam-ch‘an. When the battle was fought the latter used a new form of strategem. He caused a heavy dam to be constructed across a wooded valley and when a considerable body of water had accumulated behind it he drew the enemy into the valley below and then had the dam torn up; the escaping water rushed down the valley and swept away hundreds of the enemy and threw the rest into such a panic that they fell an easy prey to the superior numbers of the Koryŭ army. This was followed by two more victories for the Koryŭ arms.

The next year, again, the infatuated north-men flung themselves against the Koryŭ rock. Under Gen. So Son-ryŭng they advanced upon Song-do. The Koryŭ generals went out thirty miles and brought into the capital the people in the suburbs. Gen. So tried a ruse to throw the Koryŭ generals off their guard. He sent a letter saying that he had decided not to continue the march but to retire to Kitan; but he secretly threw out a strong force toward Song-do. They found every point disputed and were obliged to withdraw to Yŭng-byŭn. Like most soldiers the Koryŭ forces fought best when on the offensive and the moment the enemy took this backward step Gen. Kang Kam-ch‘an was upon them, flank and rear. The invaders were driven out of Yŭng-byŭn but made a stand at Kwi-ju. At first the fight was an even one but when a south wind sprang up which lent force to the Koryŭ arrows and drove dust into the eyes of the enemy the latter turned and fled, with the exulting Koryŭ troops in full pursuit. Across the Sŭk-ch‘ŭn brook they floundered and across the fields which they left carpeted with Kitan dead. All their plunder, arms and camp equipage fell into Koryŭ hands and Gen. So Son-ryŭng with a few thousand weary followers finally succeeded in getting across the Yalu. This was the greatest disaster that Kitan suffered at any time from her southern neighbor. Gen. So received a cool welcome from his master, while Gen. Kang, returning in triumph to Song-do with Kitan heads and limitless plunder, was met by the King in person and given a flattering ovation. His Majesty with his own hands presented him with eight golden flowers. The name of the meeting place was changed to Heung-eui-yŭk, “Place of Lofty Righteousness.” When Gen. Kang retired the following year he received six honorary titles and the revenue from three hundred houses. He was a man of small stature and ill-favored and did not dress in a manner befitting his position, but he was called the “Pillar of Koryŭ.” Many towns in the north had been laid waste during the war and so the people were moved and given houses and land. The records say that an envoy came with greetings from the kingdom of Ch‘ŭl-ri. One also came from Tă-sik in western China and another from the kingdom of Pul-lă. Several of the Mal-gal tribes also sent envoys; the kingdom of T‘am-na was again heard from and the Kol-bu tribe in the north sent envoys. In 1020 Koryŭ sent an envoy to make friends again with her old time enemy Kitan and was successful. The ambition of the then Emperor of Kitan had apparently sought some new channel. Buddhism, too, came in for its share of attention. We read that the King sent to Kyöng-ju, the ancient capital of Sil-la, to procure a bone of Buddha which was preserved there as a relic. Every important matter was referred in prayer to the Buddhistic deities. As yet Confucianism had succeeded in keeping pace with BuddhismBuddhism. In 1024 the King decreed that the candidates in the national examinations should come according to population; three men from a thousand-house town, two from a five hundredhundred-house town and one each from smaller places. Several examinations were held in succession and only those who excelled in them all received promotion. The great struggle between Buddhism and Confucianism, which now began, arrayed the great class of monks on the side of the former and the whole official class on the side of the latter. The former worked upon the superstitions of the King and had continual access to him while the latter could appeal to him only on the side of general common sense and reason. Moreover Buddhism had this in its favor that as a rule each man worked for the system rather than for himself, always presenting a solid front to the opposition. The other party was itself a conglomerate of interests, each man working mainly for himself and joining with others only when his own interests demanded. This marked division of parties was strikingly illustrated when, in 1026, in the face of vehement expostulations on the part of the officials, the King spent a large amount of treasure in the repairing of monasteries. The kingdom of Kitan received a heavy blow when in 1029 one of her generals, Tă Yŭn-im, revolted and formed the sporadic kingdom of Heung-yo. Having accomplished this he sent to the King of Koryŭ saying “We have founded a new kingdom and you must send troops to aid us.” The Koryŭ officials advised that advantage be taken of this schism in Kitan to recover the territory beyond the Yalu which originally belonged to Ko-gu-ryŭ and to which Koryŭ therefore had some remote title. Neither plan was adopted. It seemed good to keep friendly with Kitan until such time as her power for taking revenge should be past, so envoys were sent as usual, but were intercepted and held by the new King of Heung-yo. This policy turned out to be a wise one, for soon the news came that Kitan had destroyed the parvenu.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The History of Korea (Vol.1&2)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.