“But how can it be done?”

“I would that I might see the heart of Pi-gan;” and as she said it she smiled upon her lord. His soul revolted from the act and yet he had no power to refuse. Pi-gan was summoned and the executioner stood ready with the knife, but at the moment when it was plunged into the victim’s breast he cried,

“You are no woman; you are a fox in disguise, and I charge you to resume your natural shape.”

Instantly her face began to change; hair sprang forth upon it, her nails grew long, and, bursting forth from her garments, she stood revealed in her true character—a white fox with nine tails. With one parting snarl at the assembled court, she leaped from the window and made good her escape.

But it was too late to save the dynasty. Pal, the son of Mun-wang, a feudal baron, at the head of an army, was already thundering at the gates, and in a few days, a new dynasty assumed the yellow and Pal, under the title Mu-wang, became its first emperor.

Pi-gan and Mi-ja had both perished and Ki-ja, the sole survivor of the great trio of statesmen, had saved his life only by feigning madness. He was now in prison, but Mu-wang came to his door and besought him to assume the office of Prime Minister. Loyalty to the fallen dynasty compelled him to refuse. He secured the Emperor’s consent to his plan of emigrating to Cho-sŭn or “Morning Freshness,” but before setting out he presented the Emperor with that great work, the Hong-bŭm or “Great-Law,” which had been found inscribed upon the back of the fabled tortoise which came up out of the waters of the Nak River in the days of Ha-u-si over a thousand years before, but which no one had been able to decipher till Ki-ja took it in hand. Then with his five thousand followers he passed eastward into the peninsula of Korea.

Whether he came to Korea by boat or by land cannot be certainly determined. It is improbable that he brought such a large company by water and yet one tradition says that he came first to Su-wŭn, which is somewhat south of Chemulpo. This would argue an approach by sea. The theory which has been broached that the Shantung promontory at one time joined the projection of Whang-hă Province on the Korean coast cannot be true, for the formation of the Yellow Sea must have been too far back in the past to help us to solve this question. It is said that from Su-wŭn he went northward to the island Ch’ŭl-do, off Whang-hă Province, where today they point out a “Ki-ja Well.” From there he went to P‘yŭng-yang. His going to an island off Whang-hă Province argues against the theory of the connection between Korea and the Shantung promontory.

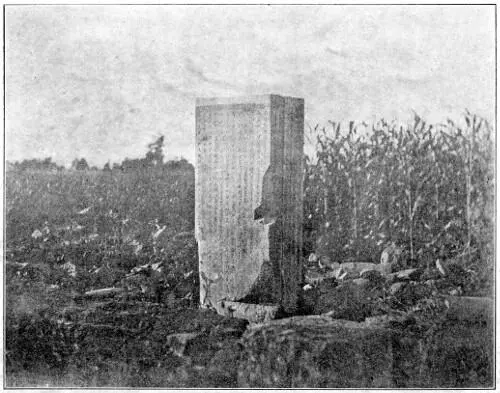

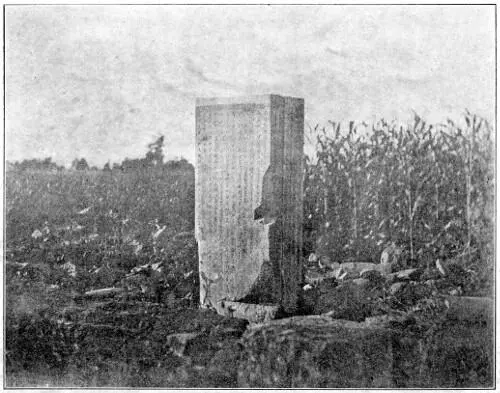

A TABLET TO KI-JA.

In whatever way he came, he finally settled at the town of P‘yŭng-yang which had already been the capital of the Tan-gun dynasty. Seven cities claimed the honor of being Homer’s birth place and about as many claim to be the burial spot of Ki-ja. The various authorities differ so widely as to the boundaries of his kingdom, the site of his capital and the place of his interment that some doubt is cast even upon the existence of this remarkable man; but the consensus of opinion points clearly to P‘yŭng-yang as being the scene of his labors.

It should be noticed that from the very first Korea was an independent kingdom. It was certainly so in the days of the Tan-gun and it remained so when Ki-ja came, for it is distinctly stated that though the Emperor Mu-wang made him King of Cho-sŭn he neither demanded nor received his allegience as vassal at that time. He even allowed Ki-ja to send envoys to worship at the tombs of the fallen dynasty. It is said that Ki-ja himself visited the site of the ancient Shang capital, but when he found it sown with barley he wept and composed an elegy on the occasion, after which he went and swore allegience to the new Emperor. The work entitled Cho-sŏ says that when Ki-ja saw the site of the former capital sown with barley he mounted a white cart drawn by a white horse and went to the new capital and swore allegience to the Emperor; and it adds that in this he showed his weakness for he had sworn never to do so.

Ki-ja, we may believe, found Korea in a semi-barbarous condition. To this the reforms which he instituted give abundant evidence. He found at least a kingdom possessed of some degree of homogeneity, probably a uniform language and certainly ready communication betweenbetween its parts. It is difficult to believe that the Tan-gun’s influence reached far beyond the Amnok River, wherever the nominal boundaries of his kingdom were. We are inclined to limit his actual power to the territory now included in the two provinces of P‘yŭng-an and Whang-hă.

We must now inquire of what material was Ki-ja’s company of five thousand men made up. We are told that he brought from China the two great works called the Si-jun and the So-jun , which by liberal interpretation mean the books on history and poetry. The books which bear these names were not written until centuries after Ki-ja’s time, but the Koreans mean by them the list of aphorisms or principles which later made up these books. It is probable, therefore, that this company included men who were able to teach and expound the principles thus introduced. Ki-ja also brought the sciences of manners (well named a science), music, medicine, sorcery and incantation. He brought also men capable of teaching one hundred of the useful trades, amongst which silk culture and weaving are the only two specifically named. When, therefore, we make allowance for a small military escort we find that five thousand men were few enough to undertake the carrying out of the greatest individual plan for colonization which history has ever seen brought to a successful issue.

These careful preparations on the part of the self-exiled Ki-ja admit of but one conclusion. They were made with direct reference to the people among whom he had elected to cast his lot. He was a genuine civilizer. His genius was of the highest order in that, in an age when the sword was the only arbiter, he hammered his into a pruning-hook and carved out with it a kingdom which stood almost a thousand years. He was the ideal colonizer, for he carried with him all the elements of successful colonization which, while sufficing for the reclamation of the semi-barbarous tribes of the peninsula, would still have left him self-sufficient in the event of their contumacy. His method was brilliant when compared with even the best attempts of modern times.

His penal code was short, and clearly indicated the failings of the people among whom he had cast his lot. Murder was to be punished with death inflicted in the same manner in which the crime had been committed. Brawling was punished by a fine to be paid in grain. Theft was punished by enslaving the offender, but he could regain his freedom by the payment of a heavy fine. There were five other laws which are not mentioned specifically. Many have surmised, and perhaps rightly, that they were of the nature of the o-hang or “five precepts” which inculcate right relations between king and subject, parent and child, husband and wife, friend and friend, old and young. It is stated, apocryphally however, that to prevent quarreling Ki-ja compelled all males to wear a broad-brimmed hat made of clay pasted on a framework. If this hat was either doffed or broken the offender was severely punished. This is said to have effectually kept them at arms length.

Another evidence of Ki-ja’s genius is his immediate recognition of the fact that he must govern the Korean people by means of men selected from their own number. For this purpose he picked out a large number of men from the various districts and gave them special training in the duties of government and he soon had a working corps of officials and prefects without resorting to the dangerous expedient of filling all these positions from the company that came with him. He recognised that in order to gain any lasting influence with the people of Korea he and his followers must adapt themselves to the language of their adopted country rather than make the Koreans conform to their form of speech. We are told that he reduced the language of the people to writing and through this medium taught the people the arts and sciences which he had brought. If this is true, the method by which the writing was done and the style of the characters have entirely disappeared. Nothing remains to give evidence of such a written language. We are told that it took three years to teach it to the people.

Читать дальше