Aritomo surrendered to his fate, allowed her to dab the barely visible damp stains off the fabric. His mother did so with the quick, precise hand movements with which she did with everything she had to do, movements all too familiar to her son.

“Leave it, it’s time,” her husband’s growling voice said. No hug, just a grab on the forearm, a quick pressure that said everything his father wanted him to say, and there needed no further words.

Afterwards, everything went very fast, mercifully fast. They stopped at the shrine to ask the ancestors for a blessing for Aritomo and then the Tenno. Their prayers were accompanied by one of the monks, whom they motivated with a small donation to a special prayer. The ceremony was short but serious, and his family’s faces had been full of pride and respect. For them, what the son had accomplished, was of extraordinary importance.

They had arrived at the train station, where, despite all their self-control and formality, at least the mother had cried silently once more, carefully hidden from the public by her relatives’ bodies. Aritomo had booked second class and enjoyed the relative luxury of a neat seat. His compartment was empty when the train rolled in, but that wouldn’t last for long. He waved and looked out of the window until the station had disappeared in the distance and not even the fiercely whirling white handkerchief of his mother was still visible. Only then did he sit down, filled with wistful thinking about his goodbye on one side, full of anticipation for the coming challenges on the other.

For half an hour, he enjoyed the silence, staring out of the window, as the suburbs of Kobe slowly moved past him, and the express train picked up some speed. At the next stop, more passengers climbed in, some joining his compartment, including an old man with a white beard, stock-still in his slightly scuffed suit, bowing slightly to Aritomo. This was rather embarrassing for the young man, but he told himself that the respect was for his uniform, not his plump baby-face, which he had somehow preserved despite his 26 years, and which may have contributed to the fact that he triggered more maternal reactions in women than romantic ones. There were also two other soldiers, apparently returning home from leave, both infantrymen, both older men, senior NCOs, as Aritomo recognized. They greeted each other with formal courtesy.

To avoid a conversation among comrades he didn’t desire at the moment, Aritomo pulled out the newspaper he had bought at the station. He glanced at the date. It was late August in the year Taisho 3 or Koki 2574, a year that, according to the powers engaged in a great war against each other in distant Europe, was also counted as 1914. The events of the war that broke out less than two months ago dominated the headlines. Aritomo had been given instructions from his superiors before he had been granted leave to only convey Japan’s official stance in conversations that their own legitimate interests – especially in Russia and China – would be duly considered, and at most some support would be given to the British allies, such as escorts. In general, however, it was believed that Japan’s involvement in this war would be marginal. Aritomo had kept his relief for this attitude to himself – other officers, superiors, had been disappointed – and found nothing in the paper that changed that impression. According to the reports, he felt that this dispute would take longer than expected, and if the imperial government played its cards properly under the Emperor’s wise leadership, Japan could emerge stronger from this mess than before.

Aritomo pondered for some time on the military and strategic implications while leafing through the rest of the paper, finding nothing of interest, then folded it neatly on his thighs. The rocking of the train had something reassuring. He hadn’t slept much last night, for he wanted to enjoy the last evening with the family, and had talked to parents and sisters until late at night, and had waken up early in the morning so he wouldn’t miss the train.

Aritomo closed his eyes and decided to go to sleep.

* * *

Fortunately, the journey was uneventful. Among the missing events he was able to avoid unpleasant and exhausting conversations with fellow travelers, the feeling of hunger and a sore back. Aritomo was very fortunate, as far as his fellow travelers was concerned, could easily satisfy himself with his mother’s supplies and, moreover, knew why he had spent the money on a second-class ticket. As the train finally arrived at Yokosuka Station in the evening, the young man was maybe tired and a bit tense, but all in all in good shape.

From the station, a bus drove regularly to the Naval Arsenal, the base where Aritomo had to report on time the next morning. Yokosuka was a big city with a glorious history dating back to 1063. Here was the first modern shipyard in Japan. Here was one of the central naval bases of Nippon Kaigun , the navy of the Empire of Greater Japan, whose proud member Aritomo had been since the age of 17.

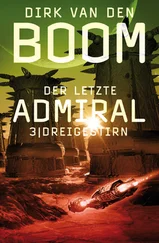

Just this one mission, his superiors had told him, and the promotion to Kaigun Daii , full lieutenant, was imminent. Aritomo’s ambition was not excessive. He didn’t dream of the admiral’s staff, only of his own command. And he would already achieve this with the rank of a lieutenant, because the division of the fleet in which he was employed offered ideal conditions for a career. Lieutenants had already been appointed commanding officers, and Aritomo himself would now serve as first officer. There were not many who could claim that at such a young age.

It was quite possible in Japan’s small but ever growing submarine fleet.

His papers were thoroughly examined when he got off the bus, and that although the officer on watch was a familiar comrade of his; he exchanged a few kind words with him. It was already dark, when Aritomo had finally reached his quarters, a small room only sparsely lit by a gas lamp, spartanly furnished.

Despite the long trip, he felt a certain restlessness that wouldn’t let him sleep. He stowed his luggage as far as it was necessary in view of his imminent departure. As a second lieutenant, he enjoyed the privilege of sharing a room with just one comrade, and at the moment the second bed was empty. A room for himself, that was something that irritated him. He had none at home, he had not enjoyed any during training, and he would serve on a submarine that barely gave him his own berth. Aritomo wasn’t used to privacy. It made him restless.

He therefore decided to give his mind some rest by taking a walk in the calmness of the evening. As he stepped outside, he unconsciously steered his steps toward the harbor, where Navy ships were moored. He marched past the mighty units, ignoring them until he came to that guarded area where the small submarine fleet of the Empire was to be found. His face was known, yet his papers were re-examined thoroughly. Then he was let into the locked district, which was so well guarded because Aritomo’s boat was stationed here.

He wandered the black shadows of the small Holland boats that still formed the backbone of the tiny fleet and where he had served at the beginning of his career. He liked to think back to that time, despite the very cramped conditions aboard the units, and the fact that these American designs were constantly struggling with all sorts of technical issues that severely affected their operational readiness and range. Aritomo had in the end served as helmsman on one of those cramped, thick-bellied boats, one of only eight crew members, and it had been a torture. But the need to build a submarine force hadn’t been ignored by the Admiralty, and so they turned to the British – who built the Holland licensee – and looked around for improvements.

Читать дальше