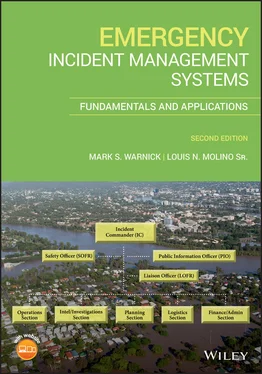

Beyond the use of the overarching NIMS method, there is also what can essentially be called the command and control system of managing an incident in the United States. This is known as the Incident Command System (ICS). ICS allows local governments and local first responders to control an incident while having the insurance policy of being able to integrate outside resources if the local agency is overwhelmed. This IMS method allows the Incident Commander to divide the responsibility of managing the incident into as many as five different tasks, each being managed by someone else, while the Incident Commander manages those supervisors and the overall incident. It is important to note that ICS is a component of NIMS, meaning that NIMS is the all‐encompassing IMS method and ICS supports NIMS. While it may sound confusing, especially this early in the book, it is not difficult to learn.

It should also be noted that there are other IMS methods used in the United States including Hospital Incident Command System (HICS). HICS was designed much like ICS so that it integrates with NIMS. HICS also integrates with ICS as well, and there is usually a seamless, or near seamless integration of the three IMS methods. Much like ICS, HICS facilitates command and control of an emergency or a disaster while enabling the seamless integration of outside resources, should they be needed.

While one could get the impression that IMS methods are useful in overwhelming and large‐scale disasters, they would be wrong. IMS methods can, and should, be utilized in daily emergencies. Local first responders and local nongovernmental agencies (e.g. American Red Cross and Salvation Army) should become proficient in the day‐to‐day use of IMS methods. By doing so, they will more effectively manage small incidents and become more proficient in the use of NIMS and ICS for when the “Big One” hits.

IMS methods can also be useful in nonphysical or catastrophic emergencies. Public safety agencies and other entities that are familiar with IMS can also utilize these same concepts to manage other types of nontraditional emergencies. These might include issues such as managing their day‐to‐day operations and nonphysical or nonemergent situations. IMS systems are extremely useful in organizing what may seem overwhelming.

IMS methods are also practical when an agency is facing a negative media blitz over a negative interaction. Most IMS methods can assist in making sure that all angles of public relations are covered. Consider the amount of crisis management that would be needed in an officer‐involved shooting, a negative story about an ambulance (or fire truck)‐involved collision, or even personnel caught in a scandal. Using an IMS method can and will help manage the crisis in the media, and if structured and utilized correctly, the IMS method can help initiate and provide ongoing damage control.

IMS can also be used to manage planned events such as sporting events, festivals, concerts, and similar events. Properly employed, IMS can be used to manage and control a multitude of incidents, including most nonemergency situations. We only need to look at past historical (major) sporting events to see how an IMS method can be used. It will also help to identify how resources can be organized so that they are highly effective and available.

If we look at Super Bowl LII that took place on 4 February 2018, we can see how managing a large planned event is possible when utilizing an IMS method. As you might imagine, the use of the Incident Command System (ICS) component, integrated with the National Incident Management System (NIMS) was used to manage this major sporting event. Those that oversaw the public safety aspect of this overwhelming planned event made sure that security was of the utmost importance. In their effort to provide top‐notch public safety, they utilized and managed over 40 federal agencies, approximately 840 different officers from 60 local and state agencies, and they incorporated the Minnesota National Guard (Moore, 2015). Beyond the previously mentioned assets, there were also a large contingency of processes and equipment integrated into the overall management of this planned event.

Not only was ICS component and NIMS used to manage a large security presence (to prevent some type of chaos from happening), but it was also used behind the scenes. There were emergency managers who planned, and who were on standby for a mass casualty event, Emergency Medical Services (EMS) personnel were strategically placed and prepared to jump into action should someone become ill or injured, or in the event a mass casualty incident occurred. Hazardous Material (HazMat) teams were also staged and ready to respond if a Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, or Explosives (CBRNE) incident occurred. Additionally, a multitude of other very specific teams were managed through the utilization of ICS component and NIMS. Some security teams were scanning for problems, while separately, other teams were ready to jump into action and take the steps needed to mitigate the effects of an emergency situation. Trying to manage a planned event, or even an emergent incident that uses a lot of personnel and equipment, would be a nightmare if not for IMS methods.

In the United States, the ICS component and its supportive companion, NIMS, has become the standard in recent years. Many people have attempted to historically date the initial development of ICS, and there has been much discussion about where the main underpinning began. No concrete date or circumstance has ever been agreed upon, even though it is usually taught that Firefighting Resources of California Organized for Potential Emergencies (FIRESCOPE) was the first official iteration of the formal system known as ICS.

In retrospect, we could say that it was a long progression of events that eventually led to the IMS methods that we now see in today's world. Many different concepts, and many different incidents have used similar methods throughout the last few hundred or more years, and some of them have been concretely identified as playing a significant role in the systems of today. Various incidents have very distinct bits and pieces of current IMS methods.

As we move onward through this chapter, there will be varying incidents discussed. These incidents may have contributed to the IMS we use today, then again, it may be coincidence that these methods were used. It should be noted that some of the history and incidents that may have contributed to modern‐day IMS methods is nothing more than speculation. On the other hand, some of these incidents are concretely documented as contributing to the current IMS methods being used today.

1.1 The Revolutionary War

It does not take much of a stretch of the imagination to say that IMS methods may have come from early military campaigns that were undertaken in the United States. Some might say that the initial fledglings may have come from other countries. Since this book primarily focuses on the United States, we will discuss only instances in the United States which may, or potentially may not have led to these systems.

Part of the reason for focusing primarily on the United States is also based on expediency. An individual could spend a lifetime trying to make connections between the gazillions (or is it quintillions) of incidents that have occurred worldwide in the last few hundred years. Most of us do not have the time, resources, or even the inclination to take review it so in depth.

We only need to look at the history of the Revolutionary War to understand that some of the principles we see in modern‐day IMS method were used during this war. Initially, the Revolutionary War had no strategy. It was nothing more than a few haphazard militia's fighting against the British when they came into or occupied their geographical location. Initially, there was no centralized commander, no strategy, and no single person, or group of people, in charge. There was no one single person that was charged with coming up with a singular or overarching strategy. In fact, most of the resistance to the British were organized locally and was not part of a larger tactic or main plan. While many of the battles were bloody, they did not follow a strategic battle plan. The objective was quite often to drive the British from the area rather than looking at the bigger picture of defeating the British in all of the colonies.

Читать дальше