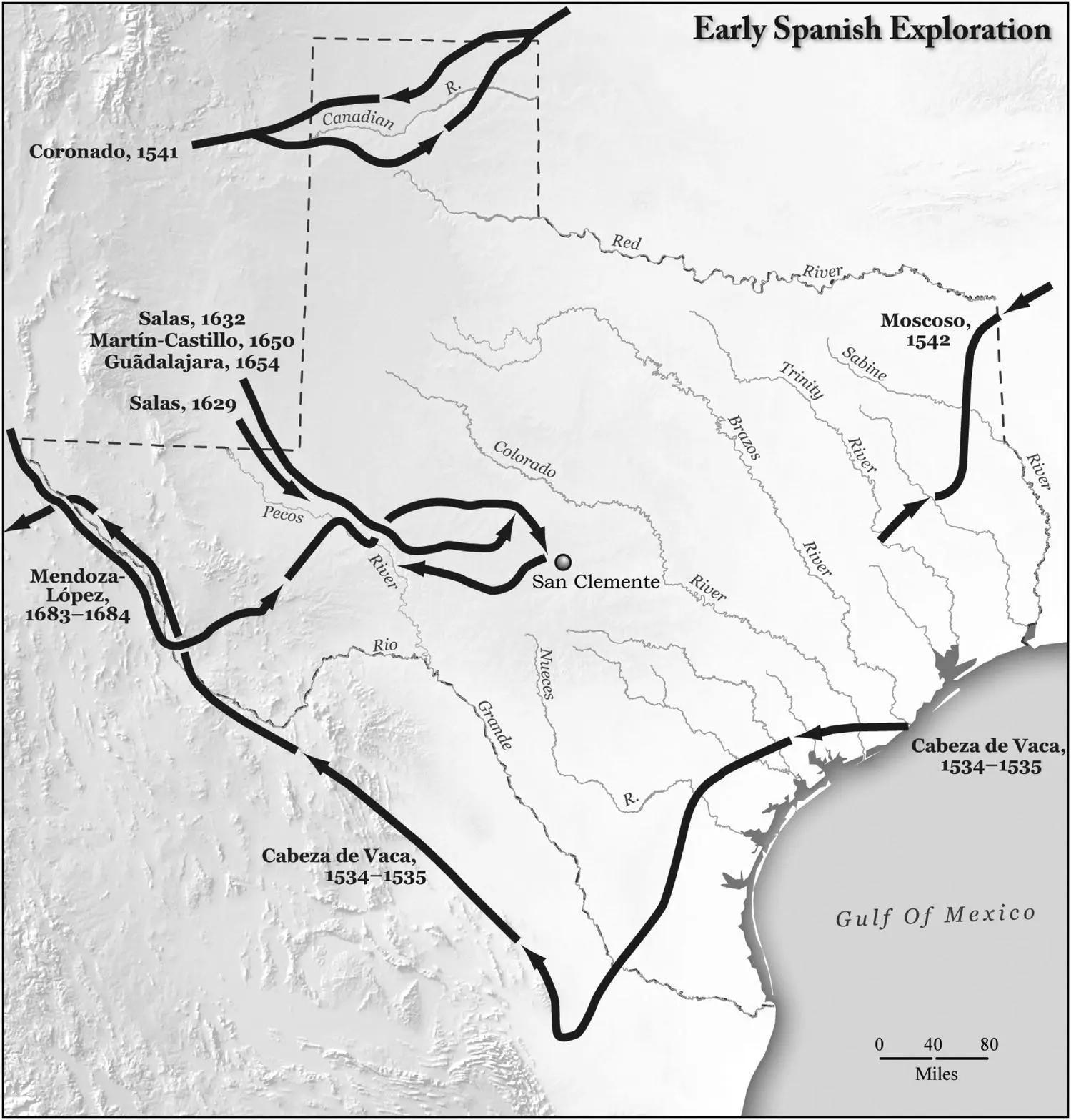

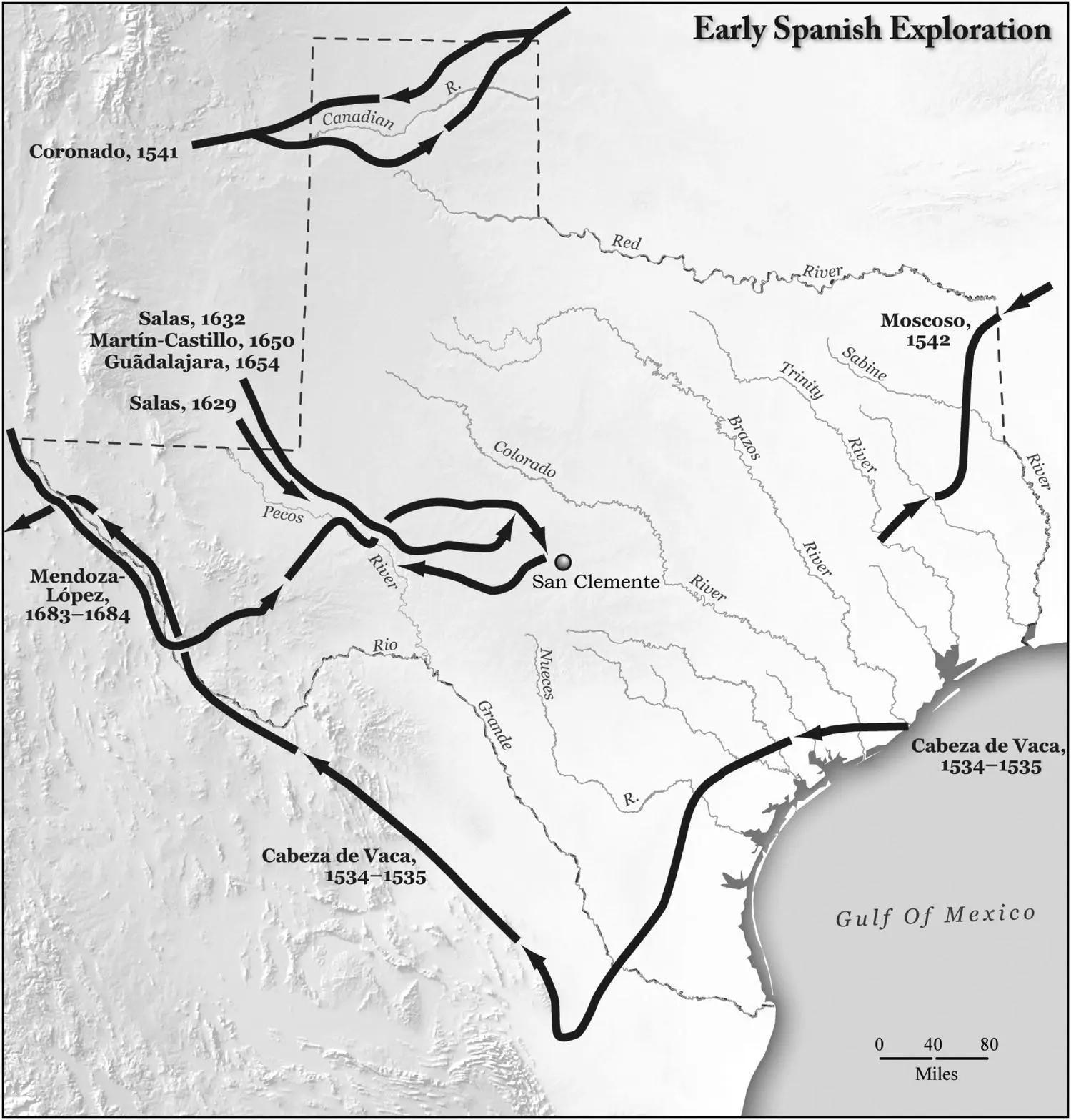

1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...37 Upon his arrival in Culiacán in 1536, Cabeza de Vaca had much to tell, including tales of riches existing in the lands somewhere north of those he had roamed. To confirm his reports, the Crown in 1539 dispatched Friar Marcos de Niza to the northern lands, with Estevanico accompanying him as a scout. In present‐day western New Mexico, the friar, supposedly viewing a Pueblo Indian town from a distant hilltop, reported upon his return of having seen a glittering city of silver and gold. Niza’s fabulous vision may be accounted for by the reflective quartz imbedded in the walls of the adobe dwellings sparkling in the sunlight, but Spanish officials interpreted his testimony as evidence of the existence of the fabled Seven Cities. Their general location was deemed Cíbola , a term meaning buffalo, which the Spaniards had heard the Indians use and now applied as a place‐name to the pueblos of the Zuñis.

Figure 1.4 Early Spanish exploration.

Historians question whether or not Niza actually traveled as far as Cíbola, but whatever the truth, Niza’s report raised expectations among the Spaniards, and the viceroy assigned Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to lead a follow‐up expedition. Coronado arrived in Zuñi country the next year, only to discover that Niza’s glittering cities were, indeed, merely adobe complexes. Conflict soon brewed with the Pueblos, for Coronado and his troops mistreated the villagers and inflicted numerous indignities upon them, even burning some Pueblo people at the stake. After this, newly generated tales of a golden kingdom called Gran Quivira induced other parties of Spaniards to venture out upon the Great Plains, but as they crossed what we know today as the Texas Panhandle, none saw anything of value to themselves or the Crown.

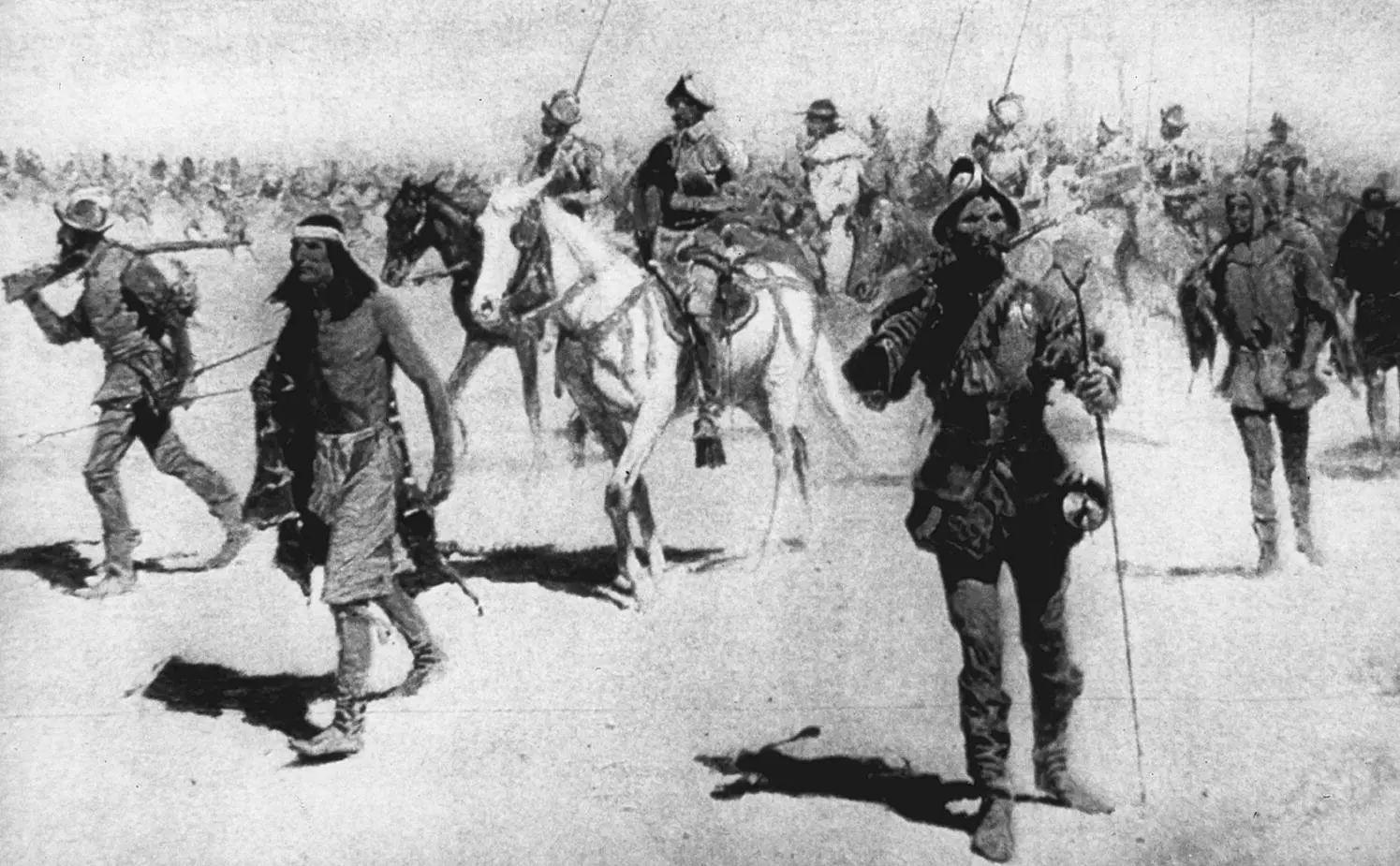

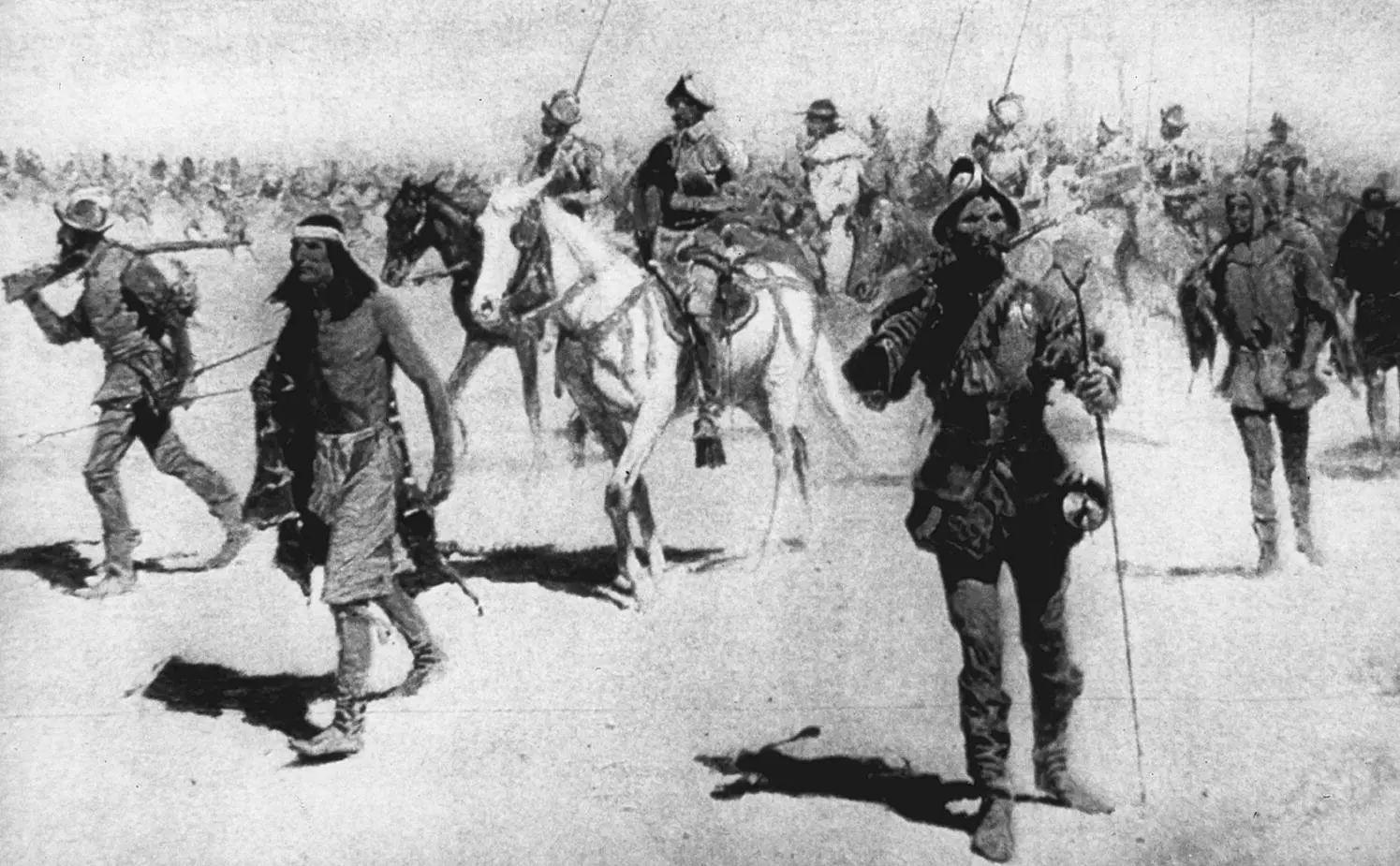

Figure 1.5 Coronado on the High Plains by Frederic Remington.

Source: Copied from a reproduction in Collier’s Magazine , December 9, 1905. University of Texas at San Antonio.

At first, Coronado refused to be disillusioned, continuing his search for Gran Quivira near the land of the Wichita tribes in Kansas ( Figure 1.5). But two years of futile searching finally convinced him to return to Mexico, and his reports of the absence of riches in the lands he had traversed discouraged further exploration of the north for another half‐century.

While Coronado was exploring the Plains, another expedition, this one led by Hernando de Soto, made its way from Florida to Alabama and across the southeastern Mississippi Valley, tracking down rumors of gold treasures and civilized cities. This quest also proved fruitless, and De Soto, despairing of his failure, took ill with fever and died in the spring of 1542. His party, now situated on the Mississippi River, was taken over by Luis de Moscoso de Alvarado, who opted to march west in hopes of reaching Mexico. During their trek, the Spaniards entered eastern Texas and may have ranged as far west as the Trinity River, near present‐day Houston County. Frustrated that they had not yet managed to reach Mexico, Moscoso and his men returned to the Mississippi, building crude boats and floating downstream and then westward along the Gulf Coast. Destiny forced the sailors ashore near present‐day Beaumont. Two months later, the 300 men arrived in the Spanish town of Panuco, Mexico, with, of course, no reports of having found riches. This report further dampened the Spaniards’ desire to explore Texas.

Competition for the North

By the early part of the seventeenth century, Spain’s New World dominion extended nearly 8000 miles, from southern California to the tip of South America. But Spain could claim no monopoly over the world discovered by Columbus, for several other European countries now competed for their share of colonies in the Western Hemisphere. The Dutch laid claim to the Hudson Valley and New Netherlands, the settlement that later became part of the English colony of New York. The French, meantime, founded Quebec in Canada and launched the occupation of Nova Scotia. As time passed, French traders pushed southwestwardly into the Great Lakes area, and by the 1650s they had infiltrated the general region around what is today the state of Wisconsin.

The most determined of the seventeenth‐century efforts were those of the English, who explored along the Atlantic Coast north of the lands chartered by Ponce de León, Pánfilo de Narváez, and Cabeza de Vaca. By the 1640s, the English empire had established solid possession of the Atlantic seaboard between northern Florida and New England. Britain now prepared to expand its mainland North American empire west, toward areas that the Spaniards regarded as exclusively their own.

Spain held an edge over its European competitors in skills required for colonization, for by the seventeenth century the trappings of Spanish civilization (much of it a legacy of the reconquista) were well in place throughout much of Latin America and ready for relocation to North American frontiers. Responsible for coordinating settlement was an autocratic king, who since the conquest of the Aztecs had passed along royal orders to political bureaucracies responsible for the day‐to‐day affairs in Spain’s respective New World colonies. Although these field officials tended to mold royal directives and laws to fit local circumstances, they implicitly recognized the king’s right to set policy and their duty to acknowledge his decisions.

The king, however, did not act haphazardly in bringing Indian lands under the Spanish flag. To the contrary, he oversaw an orderly process of expansion and settlement by employing those agencies already proven effective against the Muslims or tested on the frontiers of the New World. The military garrison and fort called the presidio , the roots of which lay in the Roman concept of praesidium (meaning a militarized region protected by fortifications), for example, was initially employed in the last half of the sixteenth century as protection against the Chichimeca Indian nations that inhabited the north‐central plateau of New Spain. From the Indian frontier north of Mexico City, the core government deployed the presidio into other regions, each fort under the direction of a presidial commander acting on behalf of the governor and whose authority outweighed that of local civilian officials. The presidio served many functions. It was a place for prisoners to complete their sentences, and it provided a walled courtyard in which to conduct peace talks with representatives of restive Indian tribes. More important, as a garrison for soldiers trained and equipped for frontier warfare, the presidio protected another frontier institution–the mission–guarding the friars in the mission compounds as they attempted to pacify and instruct newly converted congregations of Native peoples.

The practice of conducting missionary activity among the Muslim occupiers had been used in Spain during the reconquista, and it evolved into the system found in the Mexican north in the 1580s. Priests of different Catholic religious orders (such as the Franciscans or the Dominicans) staffed the missions, performing various functions relevant to exploration, conquest, and Christianization ( Figure 1.6). The missionaries sought to convert the Indians to Catholicism, establish friendly relations with hostile tribes, and, by their fortified presence at the mission, assist in retaining conquered territories for the Crown.

Читать дальше