A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Arnold, John, 1969- author.

Title: What is medieval history? / John H. Arnold.

Description: Second edition. | Medford, MA : Polity Press, 2021. | Series: What is history? | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “A rich and compelling overview of the sources and methods used by medieval historians”-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020013070 (print) | LCCN 2020013071 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509532551 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509532568 (paperback) | ISBN 9781509532582 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Middle Ages. | Middle Ages--Study and teaching. | Medievalists.

Classification: LCC D117 .A72 2020 (print) | LCC D117 (ebook) | DDC 940.1072--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013070LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013071

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

This one is for Alex

Preface to the Second Edition

The primary purpose in producing a second edition is to include some new and additional material that relates to methods and debates that have become more prominent over the decade-and-a-bit since I wrote the original book. This mainly consists of expansions to sections within Chapter 3, and a new section on ‘Globalisms’ in Chapter 4. As the original introduction admits, ‘my coverage tends towards western Europe’, and this is still the case; but the original did already reach out to a wider geography on occasion, and I have here attempted to expand upon that enlarged sense of ‘the medieval’.

I have also taken the opportunity to amend the text in minor ways in some other places, for greater clarity of expression and to include some additional examples where they are particularly illuminating. As with the original book, I remain deeply indebted to a host of colleagues and their work for my understanding of the middle ages; I should note, in particular, conversations with Ulf Büntgen, Matthew Collins, Pat Geary, Caroline Goodson, Monica Green, Eyal Poleg and Peter Sarris regarding recent work in science and archaeology. I am grateful to Pascal Porcheron at Polity for prompting my further work, and for the careful labours of Ellen MacDonald-Kramer, Sarah Dancy and others involved in its production. This second edition remains a work that aims to introduce ‘the medieval’, not in any sense claiming fully to represent it, or the fullness of its study.

Preface and Acknowledgements

This is a book about what historians of the middle ages do, rather than a history of the middle ages itself, though it will also provide a sense of that period. Each chapter focuses on a different aspect of the historian’s task, and the conditions of its possibility. Chapter 1discusses the idea of ‘the middle ages’ and its associations, and the foundational contours of academic medievalism. Chapter 2looks at sources, the possibilities and problems that they present to the historian. Chapter 3examines intellectual tools which medievalists have borrowed from other subject areas, and the insights they provide. Chapter 4tries to indicate the shape of some key and broad-ranging discussions in current historiography. The final chapter addresses the very purpose of medieval history – its present and potential roles, in academic debate and society more broadly. The book is written neither as a blankly ‘objective’ report on the field, nor as a polemical call to arms, but as an engaged survey which seeks to both explain and comment upon the wider discipline. In what follows, I assume some knowledge of, and interest in, history on the reader’s part, but little prior sense of the medieval period (roughly the years 500–1500). Rather than always listing particular centuries, I have sometimes made use of the loose division of the medieval period into ‘early’, ‘high’ and ‘late’. All that is meant by this is c .500– c .1050, c .1050– c .1300 and c .1300– c .1500. My coverage tends towards western Europe, but I have tried to indicate the greater breadth of medievalism that exists beyond; to do more would take a much bigger book.

I am indebted to various people in my attempt to chart, in so few pages, so large an area. Rob Bartlett, Mark Ormrod and Richard Kieckhefer all kindly answered particular queries at key moments. Rob Liddiard and Caroline Goodson helped me understand aspects of archaeology, Sophie Page did similarly with regard to magic and David Wells assisted my grasp of Wolfram von Eschenbach. Major thanks are due to those who very generously read and commented on individual chapters or indeed the whole book: two anonymous readers for Polity, Cordelia Beattie, Caroline Goodson, Victoria Howell, Matt Innes, Geoff Koziol and Christian Liddy; Matt and Geoff also kindly shared unpublished material with me. Any errors are entirely my own fault. Thanks are owed also to Andrea Drugan at Polity, for prompting me to write the book and for being an understanding editor during the process. As ever, I am grateful to Victoria and Zoë for giving me the support and the space in which to write.

Lastly, this book is dedicated to all those who have taught me how to teach, from my parents, Henry and Hazel Arnold, to my students past and present.

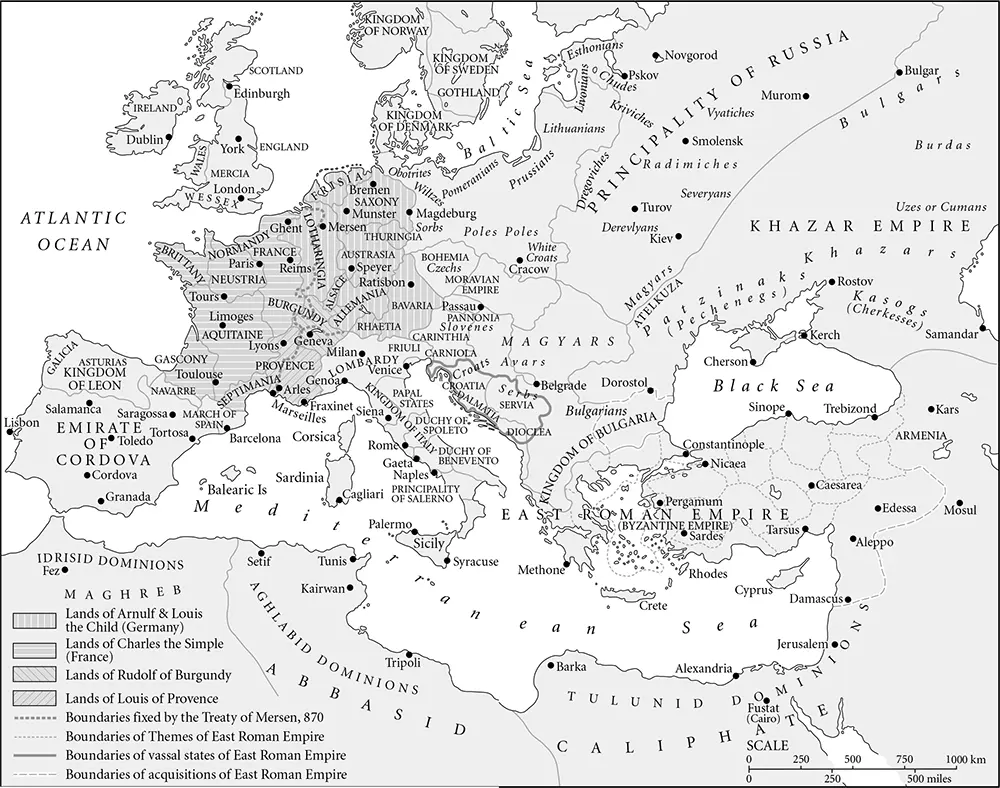

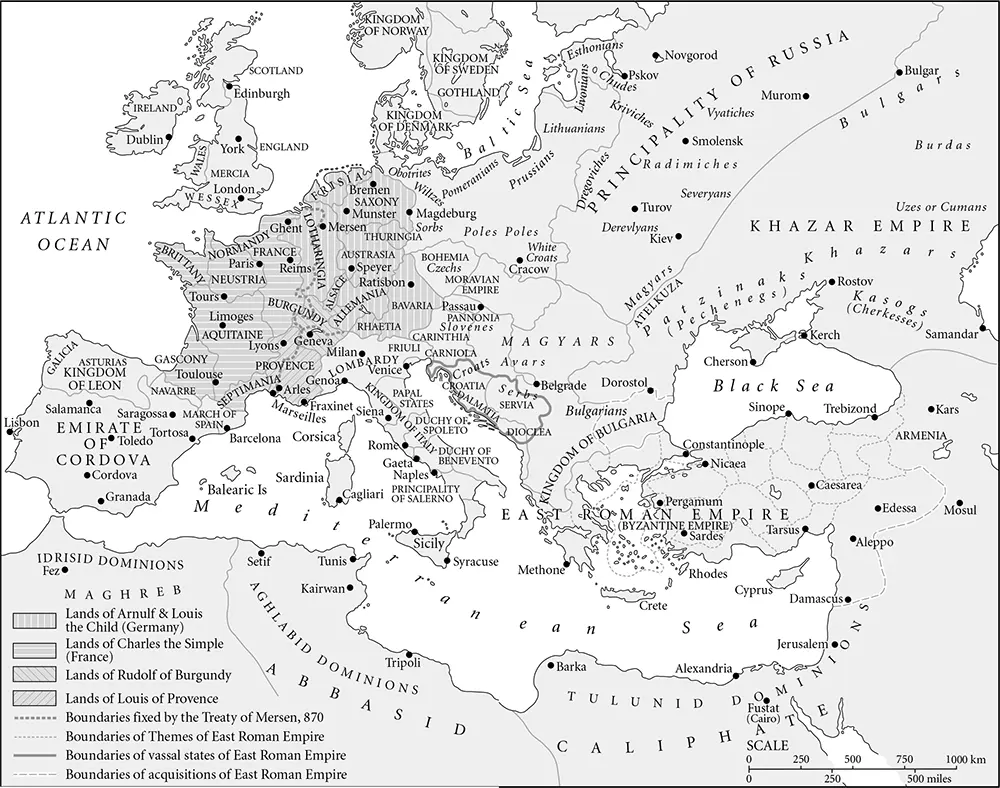

Map of Europe, c. 900

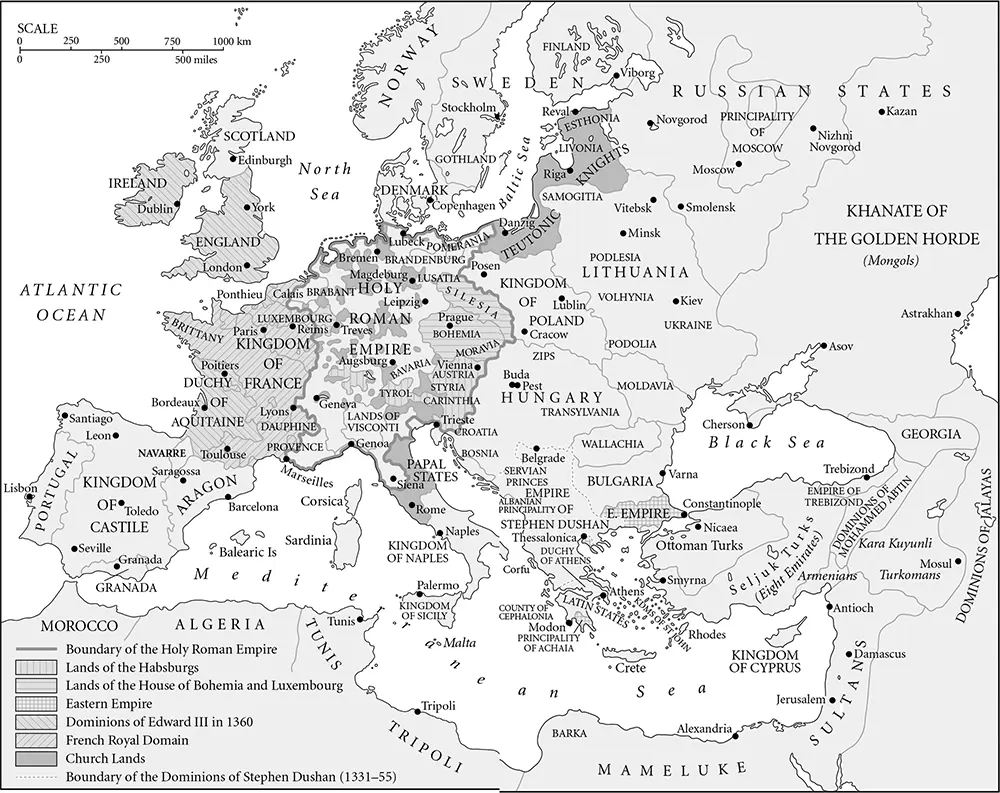

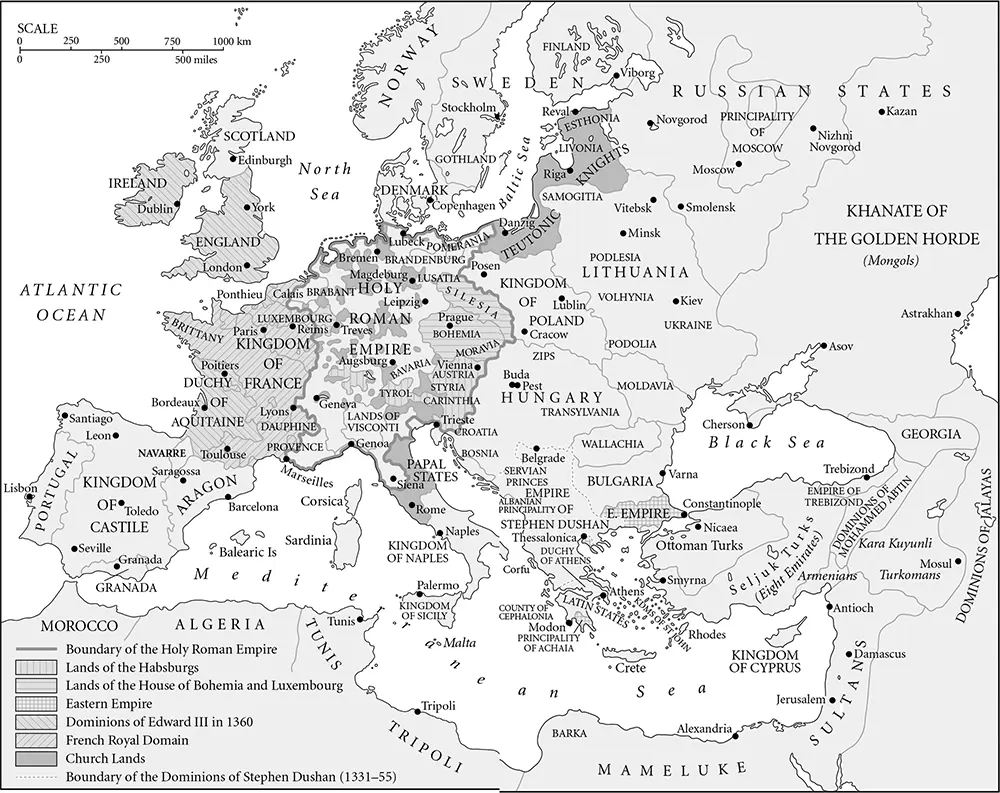

Map of Europe, c. 1360

1 Framing the Middle Ages

A Medieval Tale

The first time Bartolomeo the priest talked to them was on 9 February 1320, in the papal palace at Avignon, and his interrogation probably took up most of one day. A notary, Gerard, wrote down his words; thus they survive for us today. Three very powerful men – a cardinal, an abbot from Toulouse and the pope’s legate for northern Italy – questioned, listened and re-questioned.

Matters had begun, Bartolomeo explained, the previous year, in October. A letter had arrived from Matteo Visconti, duke of Milan, summoning the priest to his presence. And so Bartolomeo had obeyed.

He met with the Visconti conspirators (he explained to his interrogators) in a room in Matteo’s palace. Scoto de San Gemignano, a judge, was there, as was a physician, Antonio Pelacane. Initially, Matteo drew him to one side. He told the priest that ‘he wished to do Bartolomeo a great service, benefit and honour, and that he wished that Bartolomeo would do Matteo a great service, indeed the greatest, namely the greatest that anyone living could do for him; and Matteo added that he knew for certain that Bartolomeo knew well how to do the aforesaid service of which Matteo was thinking.’ He would do whatever he could, Bartolomeo protested.

Immediately Matteo called to Scoto, the judge, telling him to show Bartolomeo what he had with him. ‘Then the said lord Scoto drew out from his robe and held out and showed to Bartholomeo and Matteo a certain silver image, longer than the palm of a hand, in the figure of a man: members, head, face, arms, hands, belly, thighs, legs, feet and natural organs.’ Written on the front of the statue were these words: Jacobus papa Johannes , ‘Jacques pope John’. The present pope, John XXII, had been called Jacques d’Euze before taking the pontifical title.

Читать дальше