‘Ooh! Isn’t this beautiful?’ She seemed quite excited.

I took them round to look at the little waterfalls and showed them where the toad sometimes sat, but he wasn’t there that day. I told her what I had learnt about the plants and the animals that lived there.

‘Oh, you are a clever boy!’ said Pearl with an admiring look. ‘Isn’t he, Arnold?’

But Arnold grunted and turned his head away without saying anything. It might have been a ‘yes’ sort of grunt, but maybe not.

Finally, we went a little way down the drive and I told them about our summer outings to the Clent Hills.

‘This seems like a lovely place,’ said Pearl as we walked back towards the house.

‘Yes, I love it here,’ I grinned.

‘We’ve enjoyed talking to you,’ she said, which I thought was rather odd as Arnold hadn’t said a word. ‘But I’m afraid it’s time for us to go now. Perhaps we might be able to come and see you again. Would that be all right?’

‘Yes,’ I agreed readily. Pearl seemed to be a lovely woman – I thought I’d definitely prefer to be with her than with a lot of big boys in a home full of strangers. So, off they went and I ran in, just in time to wash my hands and join my friends for tea.

That night in the dormitory, getting into bed and falling asleep to another bedtime story that I didn’t hear the end of, I didn’t give the visitors another thought. The next day, I remembered they’d been and I wondered whether I would ever see them again. I would have liked to see Pearl, but wasn’t so sure about Arnold. And I didn’t want to hasten leaving my idyllic life with my friends and all the kind staff, so when nobody told me anything, I didn’t ask.

It must have been a few days later, maybe a week, when my housemother sat me down and told me: ‘Tomorrow, your new mother and father are going to come and collect you.’

I was shocked. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Do you remember Mr and Mrs Gallear, the nice couple who came to see you last week?’

‘Yes, but nobody said anything, so I thought they didn’t like me.’

‘Well, they did like you and they want to take you home.’

‘Are they my real mother and father?’ I asked. Children in books always seemed to have mothers and fathers, so I assumed I must have too.

‘Not your birth mother and father, no, but they want to be your foster parents.’

‘I liked her, she was nice.’

‘Good. Well, they will be your foster parents – your foster mother and foster father. You will call them Mummy and Daddy.’

‘Oh.’

‘Won’t that be nice?’

‘Tomorrow?’ I asked, suddenly welling up with tears. ‘Does it have to be tomorrow?’

‘Yes,’ she said gently, giving me a cuddle when she saw how upset I was. ‘Don’t worry, they are looking forward to taking you back with them to their house, which will become your new home. They will look after you. You’re going to have your own bedroom and you will have a lovely time making lots of new friends where they live.’

I couldn’t speak for crying. My stomach went all wobbly and I just couldn’t take all this in. I suppose I didn’t want to and it all seemed so sudden – I had no time at all.

‘Can I take my cars and my spinning top?’

‘Yes, of course you can. We’ll put them in your case to take with you. I expect you will have some more toys to play with at their house, and maybe some new clothes of your own too.’ She gave me another hug.

‘Can’t I stay here a bit longer?’

‘No, little soldier, I’m afraid you can’t, but they’re not coming till after lunch tomorrow, so you can enjoy all this afternoon and tomorrow morning in the garden. Have a good run round, play with your friends and sit in your favourite tree, whatever you like. I’ll come and find you out there when I’ve gathered all your things to pack, then we can talk some more. Would you like that?’

I nodded, as more tears trickled down my cheeks.

‘Here, take my hankie.’

It was a fine summer’s day and I walked around all my favourite places, ending up on a branch of the cedar tree. How could this happen to me? I knew others had gone to foster homes before me, but I couldn’t talk to any of them to find out if they were happy there.

At bedtime I was tearful and my housemother soothed my fears as best she could.

‘What if I don’t like it there?’ I asked her.

‘You will like it,’ she reassured me. ‘It may take you a little time to settle and get used to belonging to a proper family, getting to know them better, and all their routines. You’ll soon forget all about us. You will make new friends and I expect you’ll be starting school soon. You’ll love school, you can learn all sorts of new things at school.’

She did her best to inspire me with confidence, but it didn’t really work. For once, I didn’t fall asleep before the bedtime story finished – I don’t think I was even listening. As I lay in my bed with the lights out, a shaft of waning daylight shining across my bed from a crack in the curtains, I hoped against hope that when I woke up in the morning it would all be a dream and I wouldn’t have to leave after all.

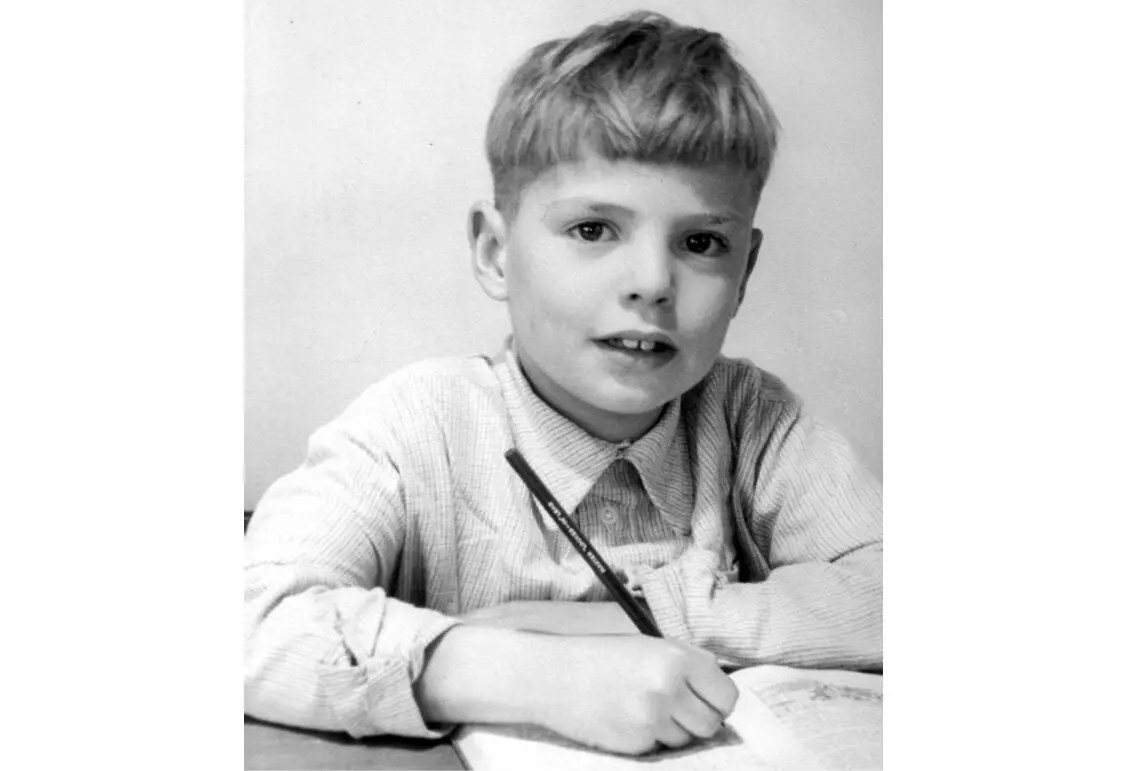

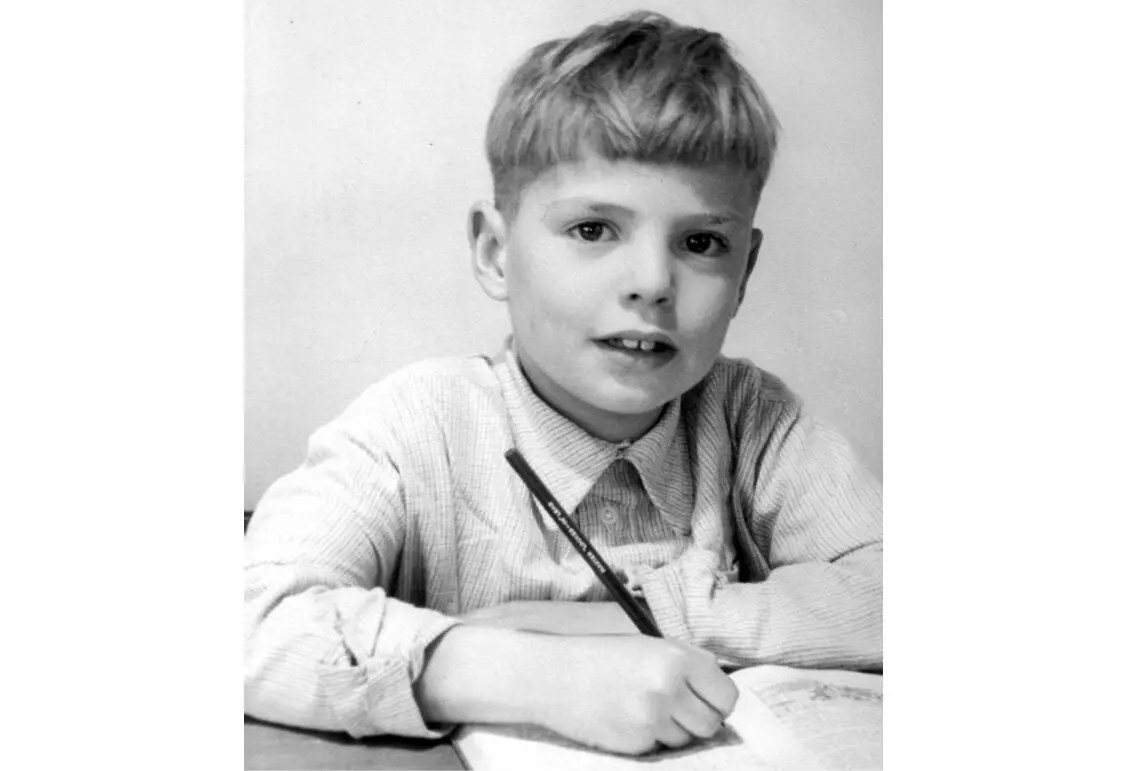

Richard at school, aged 8

CHAPTER 5

July 1959 (4 years, 8 months) – Fine healthy boy. Much more stable and happier. Full of imagination, conversation, knowledge of everyday things.

Richard’s last progress report before leaving Field House

30 August 1959 was a beautiful sunny day, but it didn’t feel sunny to me. It was the day my cosy world fell apart. That afternoon I would have to leave the only home I’d ever known – a happy home of fun and laughter with my friends, a secure place where every adult loved us and cared for us. I knew nothing of my beginnings, but I did know I didn’t want to leave Field House. I didn’t want to go and live anywhere else, I wanted to stay there for ever.

It was my last morning so I went to all my favourite places. First, to the vegetable garden, where I had ‘helped’ so often. Everything was growing well, including ‘my’ lettuces, poking up through the soil, and the runner beans I’d planted and watched growing up their canes.

‘I’m leaving today,’ I told the kindly gardener, trying to put on a brave face.

‘Are you now?’ he said. ‘We’ll miss you.’ He paused. ‘Have you got time to pick a few of these beans for the kitchen before you go? Then you can eat them for lunch.’

‘Yes, please,’ I said, perking up at the thought.

Next, I visited the Japanese garden and said goodbye to my friend the toad, who sat and croaked as if he understood.

The rest of the morning went far too quickly and when I went in for lunch, I was overjoyed that it was steak pie, mash and gravy with ‘my’ beans. It was all delicious, so I had another helping.

The housemother at our table told the other boys that I was leaving and they all came up to say goodbye to me as we left the dining room. I didn’t like them saying goodbye – I didn’t want to say goodbye, I didn’t want to go.

Finally, I went to my dormitory, where my housemother was packing my few belongings into a little, scuffed leather suitcase and ticking them off on a list.

‘I’ve packed some spare clothes for you,’ she explained in her kindest voice. I didn’t realise it at the time, but perhaps she didn’t want me to go either. ‘I’ve put in your favourite toys too.’

Читать дальше