‘We have fought against the multinationals, we have fought against the big merchant banks, we have fought against big politics, we have fought against lies, corruption and deceit … [This is] a victory for real people, a victory for ordinary people, a victory for decent people.’

Although this may sound like Salvador Allende, Chile’s Marxist leader, speaking after his election victory in 1970, it was in fact Nigel Farage, the erstwhile leader of UKIP – and incidentally a former banker himself. He uttered these words on the morning of 24 June 2016, the day after Britain’s Brexit referendum. He too was using the age-old magic of speaking in the name of ‘the people’. On the same day, however, many cosmopolitan Londoners, who were automatically excluded from this inflaming narrative, found themselves wondering who these real people were, and why they bore such a grudge against the big cities and the educated. And those who were old enough were beginning to hear echoes sounding from across the decades.

After the horrific experiences of the Second World War, not many people in Western Europe expected the masses ever again to lust after becoming a single totality. Most happily believed that if humans were free to choose what they could buy, love and believe, they would be content. For more than half a century, the word I was promoted in the public sphere by the ever-grinning market economy and its supporting characters, the dominant political discourse and mainstream culture. But now we has returned as the very essence of the movement , burnishing it with a revolutionary glow, and many have found themselves unprepared for this sudden resurrection.

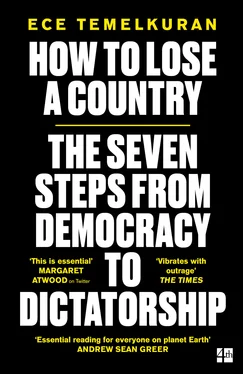

Their voice has been so loud and so unexpected that worried critics have struggled to come up with an up-to-date political lexicon with which to describe it, or counter it. The critical mainstream intelligentsia scrambled to gather ammunition from history, but unfortunately most of it dated back to the Nazi era. The word ‘fascism’ sounded passé, childish even, and ‘authoritarianism’ or ‘totalitarianism’ were too ‘khaki’ for this Technicolor beast in a neoliberal world. Yet during the last couple of years numerous political self-help books filled with quotes from George Orwell have been hastily written, and all of a sudden Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism is back on the bestseller lists after a sixty-eight-year hiatus. The hip-sounding term that the mainstream intelligentsia chose to use for this retro lust for totality was ‘rising populism’.

‘Rising populism’ is quite a convenient term for our times. It both conceals the right-wing ideological content of the movements in question, and ignores the troubling question of the shady desire of I to melt into we . It masterfully portrays the twisted charismatic leaders who are mobilising the masses as mad men, and diligently dismisses the masses as deceived, ignorant people. It also washes away the backstory that might reveal how we ended up in this mess. In addition to this, there is the problem that the populists do not define themselves as ‘populists’. In a supposedly post-ideology world, they are free to claim to be beyond politics, and above political institutions.

Political thought has not been ready to fight this new fight either. One of the main stumbling blocks is that the critics of the phenomenon have realised that ‘rising populism’ is the strange fruit of the current practice of democracy. As they looked deeper into the question they soon discovered that it wasn’t a wound that, all of a sudden, appeared on the body politic, but was in fact a mutant child of crippled representative democracy.

Moreover, a new ontological problem was at play thanks to the right-wing spin doctors. Academics, journalists and the well-educated found themselves included in the enemy of the people camp, part of the corrupt establishment, and their criticism of, or even their carefully constructed comments on, this political phenomenon were considered to be oppressive by the real people and the movement’s spin doctors. It was difficult for them to adapt to the new environment in which they had become the ‘oppressive elite’ – if not ‘fascists’ – despite the fact that some of them had dedicated their lives to the emancipation of the very masses who now held them in such contempt. One of them was my grandmother.

‘Are they now calling me a fascist, Ece?’

My grandmother, one of the first generation of teachers in the young Turkish republic, a committed secular woman who had spent many years bringing literacy to rural children, turned to me one evening in 2005 while we were watching a TV debate featuring AKP spin doctors and asked, ‘They did say “fascist”, right?’ She dismissed my attempt to explain the peculiarities of the new political narratives and exclaimed, ‘What does that even mean, anyway? Oppressive elite ! I am not an elite. I starved and suffered when I was teaching village kids in the 1950s.’

Her arms, having been folded defensively, were now in the air, her finger pointing as she announced, as if addressing a classroom, ‘No! Tomorrow I am going to go down to their local party centre and tell them that I am as real as them.’ And she did, only to return home speechless, dragging her exhausted eighty-year-old legs off to bed at midday for an unprecedented nap of defeat. The only words I could get out of her were: ‘They are different, Ece. They are …’ Despite her excellent linguistic skills, she couldn’t find an appropriate adjective.

I was reminded of my grandmother’s endeavour when a seventy-something American woman approached me with some hesitation after a talk I gave at Harvard University in 2017. Evidently one of those people who are hesitant about bothering others with personal matters, she gave me a fast-forward version of her own story: she had been a Peace Corps volunteer in the 1960s, teaching English to kids in a remote Turkish town, then a dedicated high school teacher in the USA, and since her retirement she had become a serious devotee of Harvard seminars. She was no less stunned than my grandmother at the fact that Trump voters were calling her a member of the ‘oppressive elite’. She said, ‘I try to explain myself to them when we talk about politics, but …’ A ruthless political narrative that labelled her lifelong labours as both unimportant and oppressive was gaining traction. In this new political scenario, she found herself trying to crawl out of the deep hole that had been dug for elites, a hole that was proving too deep for her frail legs. The more serious problem was that the real people never asked her to join them, or offered to help her climb out of the hole. All they demanded from her was ‘respect’.

‘Respect is something I hear a lot about from Trump voters. The spirit of the sentiment is often: “Maybe Trump’s a jerk, maybe he won’t do what he says he will, but he acts as if people like me are important, and the people who disrespect me aren’t.”’

In September 2016 the Chicago Tribune published a Bloomberg opinion piece by Megan McArdle. ‡As she had expressed before in other columns, McArdle was stunned by the fact that any conversation with Trump supporters was usually brought to a halt by the word ‘respect’. When Trump entered the scene, bucketloads of ‘respect’ flushed through American politics, and Hillary Clinton’s ‘deplorables’ comment about Trump supporters gave them yet another angle to exploit. Suddenly the media was questioning its own ability to respect ordinary people. Self-criticism among journalists, together with the massive attacks on the media from Trump supporters for being disrespectful towards real people , became impossible to ignore. So much so that after the election the New York Times opened a ‘Trump voters only’ section in which they could express themselves free from the condescending filter of the elitist media. Even if the new platform might have functioned as a rich source of raw research material for academics, it was definitely a triumph for Trump voters in their quest for gaining respect, a victorious battle in the long war of recognition.

Читать дальше