There will be far more complicated evolutionary steps in the eons to come, changes so extreme that entire branches of life will emerge. These changes—the products of mutations, insertions, gene rearrangements, and the horizontal transfer of genes from one species to another—will create organisms with bilateral symmetry, stereoscopic vision, and even consciousness.

By comparison, this early evolutionary step looks, at first, to be rather simple. It is a circuit. A gene circuit.

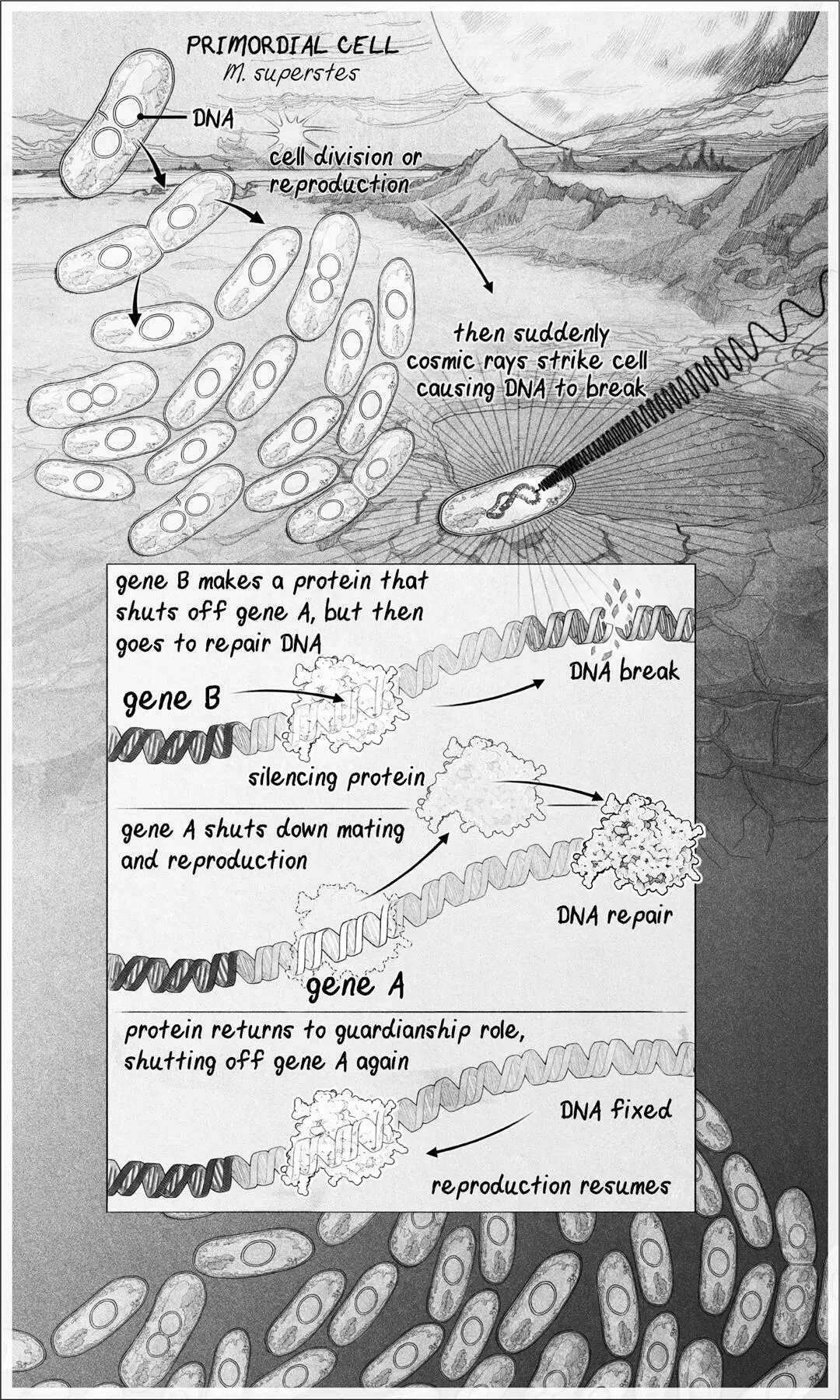

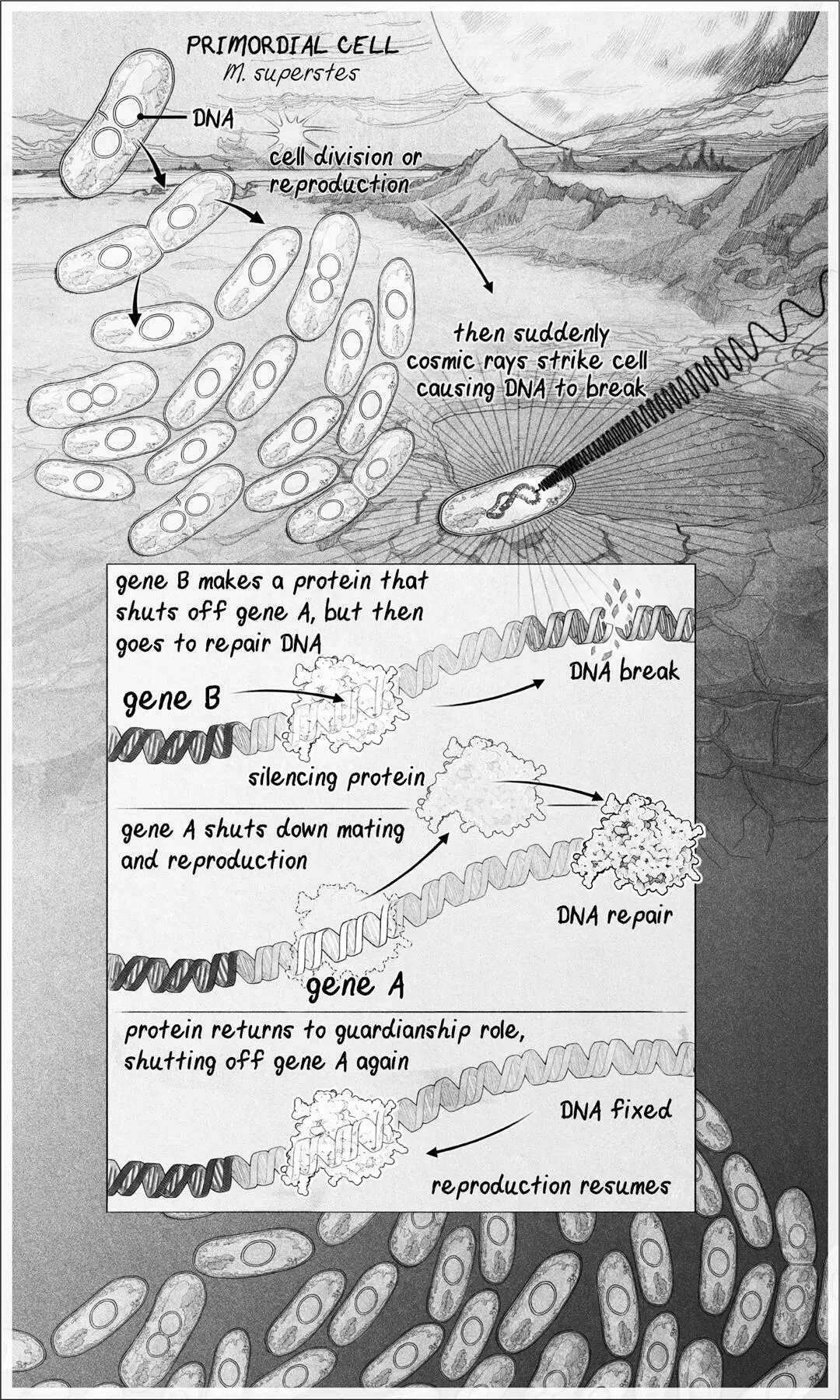

The circuit begins with gene A, a caretaker that stops cells from reproducing when times are tough. This is key, because on early planet Earth, most times are tough. The circuit also has a gene B, which encodes for a “silencing” protein. This silencing protein shuts gene A off when times are good, so the cell can make copies of itself when, and only when, it and its offspring will likely survive.

The genes themselves aren’t novel. All life in the lake has these two genes. But what makes M. superstes unique is that the gene B silencer has mutated to give it a second function: it helps repair DNA. When the cell’s DNA breaks, the silencing protein encoded by gene B moves from gene A to help with DNA repair, which turns on gene A. This temporarily stops all sex and reproduction until the DNA repair is complete.

This makes sense, because while DNA is broken, sex and reproduction are the last things an organism should be doing. In future multicellular organisms, for instance, cells that fail to pause while fixing a DNA break will almost certainly lose genetic material. This is because DNA is pulled apart prior to cell division from only one attachment site on the DNA, dragging the rest of the DNA with it. If DNA is broken, part of a chromosome will be lost or duplicated. The cells will likely die or multiply uncontrollably into a tumor.

With a new type of gene silencer that repairs DNA, too, M. superstes has an edge. It hunkers down when its DNA is damaged, then revives. It is superprimed for survival.

THE EVOLUTION OF AGING.A 4-billion-year-old gene circuit in the first life-forms would have turned off reproduction while DNA was being repaired, providing a survival advantage. Gene A turns off reproduction, and gene B makes a protein that turns off gene A when it is safe to reproduce. When DNA breaks, however, the protein made by gene B leaves to go repair DNA. As a result, gene A is turned on to halt reproduction until repair is complete. We have inherited an advanced version of this survival circuit.

And that’s good, because now comes yet another assault on life. Powerful cosmic rays from a distant solar eruption are bathing the Earth, shredding the DNA of all the microbes in the dying lakes. The vast majority of them carry on dividing as if nothing has happened, unaware that their genomes have been broken and that reproducing will kill them. Unequal amounts of DNA are shared between mother and daughter cells, causing both to malfunction. Ultimately, the endeavor is hopeless. The cells all die, and nothing is left.

Nothing, that is, but M. superstes . For as the rays wreak their havoc, M. superstes does something unusual: thanks to the movement of protein B away from gene A to help repair the DNA breaks, gene A switches on and the cells stop almost everything else they are doing, turning their limited energy toward fixing the DNA that has been broken. By virtue of its defiance of the ancient imperative to reproduce, M. superstes has survived.

When the latest dry period ends and the lakes refill, M. superstes wakes up. Now it can reproduce. Again and again it does so. Multiplying. Moving into new biomes. Evolving. Creating generations upon generations of new descendants.

They are our Adam and Eve.

Like Adam and Eve, we don’t know if M. superstes ever existed. But my research over the past twenty-five years suggests that every living thing we see around us today is a product of this great survivor, or at least a primitive organism very much like it. The fossil record in our genes goes a long way to proving that every living thing that shares this planet with us still carries this ancient genetic survival circuit, in more or less the same basic form. It is there in every plant. It is there in every fungus. It is there in every animal.

It is there in us.

I propose the reason this gene circuit is conserved is that it is a rather simple and elegant solution to the challenges of a sometimes brutish and sometimes bounteous world that better ensures the survival of the organisms that carry it. It is, in essence, a primordial survival kit that diverts energy to the area of greatest need, fixing what exists in times when the stresses of the world are conspiring to wreak havoc on the genome, while permitting reproduction only when more favorable times prevail.

And it is so simple and so robust that not only did it ensure life’s continued existence on the planet, it ensured that Earth’s chemical survival circuit was passed on from parent to offspring, mutating and steadily improving, helping life continue for billions of years, no matter what the cosmos brought, and in many cases allowing individuals’ lives to continue for far longer than they actually needed to.

The human body, though far from perfect and still evolving, carries an advanced version of the survival circuit that allows it to last for decades past the age of reproduction. While it is interesting to speculate why our long lifespans first evolved—the need for grandparents to educate the tribe is one appealing theory—given the chaos that exists at the molecular scale, it’s a wonder we survive thirty seconds, let alone make it to our reproductive years, let alone reach 80 more often than not.

But we do. Marvelously we do. Miraculously we do. For we are the progeny of a very long lineage of great survivors. Ergo, we are great survivors.

But there is a trade-off. For this circuit within us, the descendant of a series of mutations in our most distant ancestors, is also the reason we age.

And yes, that definite singular article is correct: it is the reason.

TO EVERYTHING THERE IS A REASON

If you are taken aback by the notion that there is a singular cause of aging, you are not alone. If you haven’t given any thought at all as to why we age, that’s perfectly normal, too. A lot of biologists haven’t given it much thought, either. Even gerontologists, doctors who specialize in aging, often don’t ask why we age—they simply seek to treat the consequences.

This isn’t a myopia specific to aging. As recently as the late 1960s, for example, the fight against cancer was a fight against its symptoms. There was no unified explanation for why cancer happens, so doctors removed tumors as best they could and spent a lot of time telling patients to get their affairs in order. Cancer was “just the way it goes,” because that’s what we say when we can’t explain something.

Then, in the 1970s, genes that cause cancer when mutated were discovered by the molecular biologists Peter Vogt and Peter Duesberg. These so-called oncogenes shifted the entire paradigm of cancer research. Pharmaceutical developers now had targets to go after: the tumor-inducing proteins encoded by genes, such as BRAF , HER2 , and BCR-ABL . By inventing chemicals that specifically block the tumor-promoting proteins, we could finally begin to move away from using radiation and toxic chemotherapeutic agents to attack cancers at their genetic source, while leaving normal cells untouched. We certainly haven’t cured all types of cancer in the decades since then, but we no longer believe it’s impossible to do so.

Читать дальше