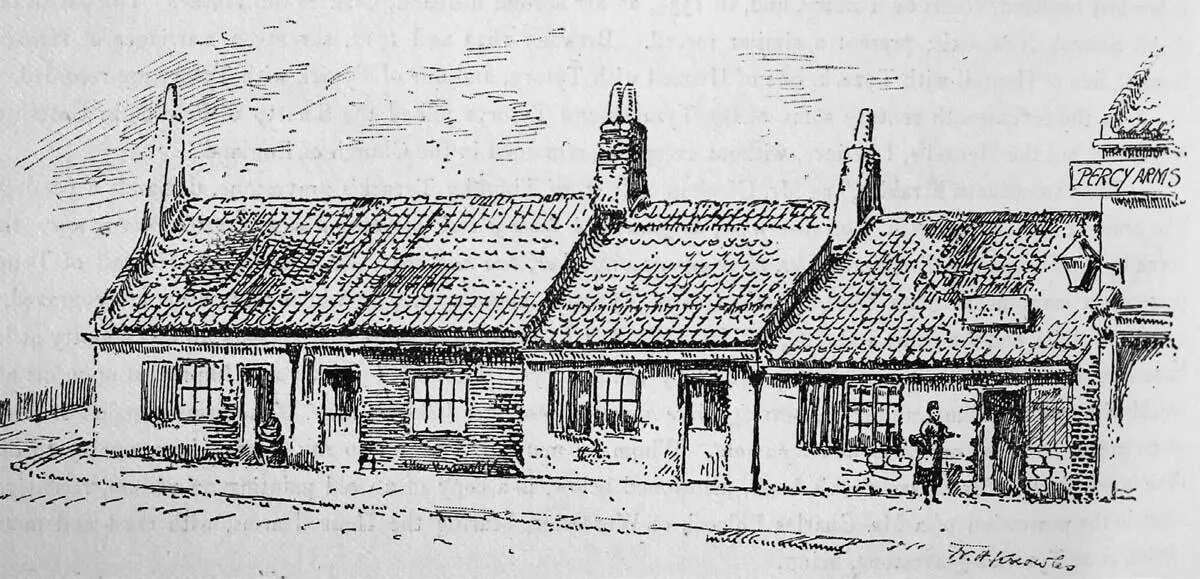

Just as Henry Hutton worked at – was – the interface between landowner and manual workers, his house stood on the edge in more than one sense. Sidegate, their street, was one of the first to burst out of the still intact medieval town walls, and while open land surrounded it on both sides, a stroll down the hill took you back to the bustle of Newcastle. Away to the north it led across the Great Northern coalfield, engine of England’s prosperity.

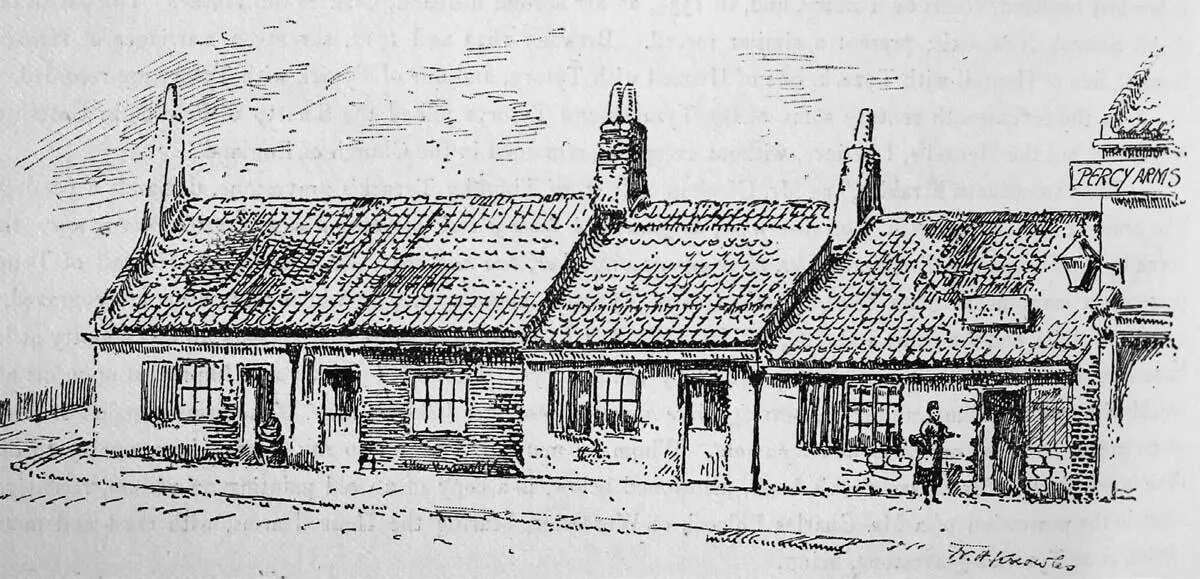

The ‘low’ cottage of Hutton’s birth.

Charles, Henry’s youngest son, came into the world on 14 August 1737. A fortnight or so later his parents took that stroll downhill to the parish church of St Andrew’s, just inside the town wall – stubby tower, Norman interior, bright new set of bells – and he was baptised.

For a few years, all was well. There were games with other children in the street; there were fights. Ladies liked little Charles; they thought him uncommonly docile and good-natured.

The Huttons sent some, perhaps all, of their children to school. On the walk from their cottage to St Andrew’s they passed Gallowgate (actual hangings were a rarity by Hutton’s time: one every few years, if that). And on the corner of Gallowgate a house stuck out awkwardly into the street. In it an old Scots woman kept what the usage of the day optimistically called a school. That is, she took in a few of the local children and endeavoured to show them how to read, with the aid of a Bible. Charles Hutton remembered her as no great scholar; when she came to a word she couldn’t read, she would tell the children to skip it because ‘it was Latin’. But he did learn to read.

In the summer of Charles’s sixth year his father died. Swiftly his mother remarried; with several children to keep, the youngest of them five years old, there was perhaps little real choice. Their new father, Francis Frame, occupied a lower station than Henry Hutton. He was an ‘overman’ in one of the collieries: a labourer, but one who was also employed to superintend the others. Not necessarily literate, not necessarily numerate: there was a system of marks and tally sticks to avoid the need for that. His pay might have been half that of a viewer, and he basically worked underground. And he had to live near the pit. Shifts might start in the small hours, even at midnight, and you couldn’t be walking a mile or two in the dark just to get to the colliery. The family left the house in Newcastle, and moved north into the coalfield itself. And coal changed from a distant background, a what-my-dad-does, to an immediate daily reality for Charles Hutton.

Hundreds of thousands of tons of it went down the river each year, and the market was growing all the time. Over the course of the eighteenth century the industrial revolution and the steam engine would increase Britain’s hunger for coal to stupendous levels. As the coal trade grew it expanded away from the river, north and south; new collieries were opened and new wagon routes built to serve them. Landowners gambled huge sums on the chance of reaching a profitable seam, but they also told themselves – and believed – that they were doing a public service: providing jobs, providing coal.

The so-called Grand Alliance of colliery owners was sinking new pits on north Tyneside, where coal to last hundreds of years lay undug. The villages there – Jesmond, Heaton, Long Benton – would now be the Hutton family’s world. This was the true coal country. The landscape of the Great Northern coalfield was all pits and pit villages; the hills and the fields, the river and the tearing clouds formed little more than a scenic backdrop. Streams were everywhere, making steep little valleys and shaping where you could build, where you could walk. And where you could dig. The wet got into the pits, and a mine on north Tyneside could raise a dozen or more times as much water as it did coal. Horses plodded around horse-gins to wind the ropes that brought it all up, and unwind them again to send the men down.

The members of the Grand Alliance were technophiles, and they installed the new atmospheric engines designed by Thomas Newcomen – forerunners of the steam engine – at their pitheads to do some of the winding work. The machines were cheaper to run than horses, but they were loud, and they added to the noise, the smoke and the dust. It’s hard to get a sense of it today, now that the pits are closed and the collieries built over with smart modern houses. On a clear day you can see down from Long Benton, where the Huttons worked, to the spires of Newcastle’s churches, and beyond to the rolling country south of the river. There are still some open fields nearby – playing fields, now – and the long line of the old wagonway, down towards the river, remains as a peaceful footpath; birds sing in the hedges.

In the 1740s it was a very different place. The wagonway had wooden rails, and the Long Benton colliery and its neighbours ran an endless procession of horse-drawn wagons on them, taking the coal down to the staithes at the river’s edge. The spires of Newcastle may have been visible through the clouds of coal dust and smoke, but they represented a distant, unattainable world.

Nearly all collieries provided housing for the underground workers, and the Huttons presumably lived in such a dwelling. Long gone now, the miners’ cottages were packed in tightly, in rows as close to the pit mouth as could be managed. They were drab and uniform; two rooms was usual, with an extra chamber in the roof. Quite a few had gardens for vegetables, or even a pig or cow, or some hens. The tradition on the Great Northern coalfield – at least later – was for growing prize leeks.

The pit villages were isolated physically and socially. It was an unusual environment, supporting an unusual kind of work. The miners made a close-knit world, with massive revelry at weddings and christenings (and any other excuse): roaring bagpipes and roaring men; hilarious, vulgar, open-hearted.

Middle-class visitors typically found the miners and their families shocking, barbarous, uncivilised. Translated, that probably means miners’ pubs were noisy, their homes not absolutely spotless, and their knowledge of scripture of a slightly less than prizewinning standard. The miners’ world may have been rough and simple; squalid it was not.

They were proud of their appearance. Like sailors, you could tell the miners anywhere by their clothes: checked shirts, jackets and trousers with a red tie and grey knitted stockings. Long hair in a pigtail. And of course the pall of coal dust, almost impossible to wash out completely. Rings of it circled their eyes, and it made the cuts and abrasions of underground work heal into distinctive blue scars.

Charles Hutton would remember his stepfather Francis Frame as a kind man. But he was not Lord Ravenscroft’s land steward, nor anything like it, and there was no avoiding the fact that the family’s expectations had fallen. There had probably never been any question about what work the boys would go into, but if there had been hopes of climbing the ladder to become viewers and overmen they probably now hoped for nothing more than the status of plain coal hewers.

And by the age of six, or certainly by the age of eight, little Charles was old enough to start work. One report says he spent some time operating a trapdoor in the pits. For a miner’s lad this was typical entry-level work, done by the youngest boys. Different areas of the pit were isolated from each other by trapdoors, usually kept shut to make sure the air flowed where it was supposed to and reduce the risk of gas build-up and explosion. Each trap had a boy to pull the cord that opened it, and shut it again after men or coals had passed. Boring but crucial work; mines blew to smithereens if a trapper lad fell asleep on the job and let the bad air reach the candles. Solitude, silence and darkness worse than any prison. You learned not to fear the dark.

Читать дальше