The rector looked more worried than ever.

‘I thought of that, but Mrs Price refused to consider it. She is a great sufferer with bad legs and …’

Margaret had her own opinion about Mrs Price’s bad legs, which she thought were used as an excuse not to work.

‘Well, send her away. I can look after both of us – truly I can.’

The rector gave a little groan.

‘It can’t be done, pet. You see, there’s Mr Price. He doesn’t really charge me, as you know, he throws me in, as it were, with his position of verger. But I did speak to the archdeacon about you, asking his opinion as to whether you could possibly live here. But he said he thought an old bachelor like myself was a most unsuitable guardian for a little girl.’

Margaret made a face.

‘How silly of the archdeacon. Well, if I’m not staying at Saltmarsh House and I’m not staying here, where am I going?’

The rector had spent many hours on his knees asking God for advice and help in handling this interview. He was convinced help and advice would be given to him if only he was spiritually able to receive it. Now, with Margaret’s brown eyes gazing up at him, he felt painfully inadequate and ashamed. Why was he so ineffectual a man that he had not risen in the world so that he had the wherewithal to succour children such as Margaret?

‘I’m afraid, pet, you are not going to care for either of the two solutions I have to offer. You are, I know, a brave child, but now you will need all your fortitude.’

Margaret stiffened to take what was coming.

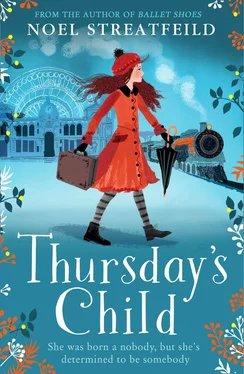

‘Whatever it is,’ she said, ‘I’m still me – Margaret Thursday. Go on, tell me.’

Since Margaret had no surname it was the rector who had chosen Thursday, the day on which he had found her. He thought it touching that she was so proud of it.

‘I have, of course, tried everywhere to find you a home in this parish. I have succeeded in only one case. Your school. I know you do not much care for your teacher, but though perhaps she has a difficult nature she is a good Christian woman.’

‘I have never seen anything very Christian about her,’ said Margaret. ‘I think she’s hateful.’

The rector shook his head.

‘You must not make such harsh judgements, pet, especially now that she is trying to help. She has offered you a home in the school. Her suggestion is that you should do schoolwork in the mornings and housework in the afternoons and …’

But there the rector stopped for Margaret, her eyes flashing, had jumped to her feet.

‘I’d never live there, I’d rather die. You should see that poor Martha who works there now. I think she beats her and there are black beetles in the kitchen. Anyway, do you think I’d be a maid in my own school where, whatever anybody else thinks, I know I’m not just as good as anybody else but a lot better? Remember I came with three of everything and of the very best quality.’

The rector screwed himself up to tell Margaret his alternative suggestion.

‘The archdeacon has told me of an institution of which his brother is a governor. It is an orphanage, but an exceptionally pleasant place, I understand. He has offered to speak to his brother about you.’

Margaret swallowed hard, determined not to cry.

‘Where is it?’

‘Staffordshire.’

Margaret tried to recall the globe in the school classroom. She was now in Essex, surely Staffordshire was miles away.

‘Near Scotland?’ she suggested.

‘Oh, not so far as that. The orphanage is near a town called Wolverhampton. I do not know it myself.’

Margaret was so dispirited her voice was a whisper.

‘Would they take me for nothing?’

‘Yes.’

‘And I would be treated like all the other girls?’

‘Girls and boys – orphanages take both.’

Margaret gulped hard but she would not cry.

‘Then that’s where I’ll go. If I can’t stay here I’d rather go to a place where I am treated as a proper person.’

The orphanage – called St Luke’s – was, so pamphlets pleading for funds said, ‘A home for one hundred boys and girls of Christian background’. The building had been given and endowed by a wealthy businessman who had died in 1802. He had stipulated in his will that though the actual building was near Wolverhampton no child from any part of the country who was an orphan and a Christian was to be refused a vacancy provided they were recommended by a clergyman of the Established Church.

‘So splendid of the archdeacon to recommend you,’ the rector said to Margaret, ‘for he carries more weight than I could hope to do, and then, of course, there is his brother who is a governor.’

One of the worries of the committee who ran St Luke’s was how to collect their children. Most of them were too young to travel alone, especially if the journey included changing trains and crossing London. So a system had been devised by which new arrivals were collected in groups. When possible, new entrants were delivered to London by their relatives or sponsors, and there they were met by someone from the orphanage.

The rector came up to Saltmarsh House each time there was news about Margaret, but it was March before he arrived with definite information. Hannah always considered it unseemly that the rector should come into the kitchen, so he was led into the drawing room, which was cold, for neither Miss Sylvia nor Miss Selina came down until teatime so the fire was never lit until after luncheon.

‘Stay and hear the news,’ the rector told Hannah, ‘for it concerns you.’ He opened a letter from the archdeacon and read.

I have now heard from the chairman of the committee of good ladies who run the domestic affairs of the orphanage. She says there are two members of one family to be admitted at the same time as your protégée Margaret Thursday. They are to meet in the third class waiting room at Paddington Station on the 27th of this month at 1 p.m. The train does not leave until 2.10, but the children will be given some sort of meal. They say Margaret Thursday should bring no baggage as all will be provided.

Hannah was appalled.

‘No baggage indeed! That’s a nice way for a young lady to travel. Margaret came to us with three of everything and she is leaving us the same way, not to mention something extra I’ve made for Sundays.’

‘I think,’ the rector explained, ‘the orphans wear some kind of uniform.’

‘So they said on that first form they sent,’ Hannah agreed, ‘but there was no mention of underneath.’ Then she blushed. ‘You will forgive me mentioning such things, sir.’

The rector dropped the subject of underneath.

Do you think arrangements could be made for someone to stay with your ladies for one day while you take Margaret to Paddington Station? I would take her myself, but the archdeacon says …’ He broke off, embarrassed. Hannah understood.

‘No, better I should go. It’s not a gentleman’s job. We’ll have to book on the carrier’s cart to the railway junction for London.’

The rector was glad to do something.

‘I shall see to that, indeed, I will arrange everything. All you have to do is to be ready by the 27th. Can you manage that, Margaret, my pet?’

Margaret had been waiting for a chance to speak.

‘Can I take my baby clothes with me?’

‘Whatever for?’ gasped Hannah.

‘I don’t quite see …’ the rector started to say, but Margaret interrupted him.

‘I don’t want to get to this St Luke’s looking like a charity child. If I show my baby clothes – three of everything and of the very best quality – they’ll know I’m somebody.’

The rector looked at Margaret’s flashing eyes. He spoke firmly for he wanted her to remember his words.

Читать дальше