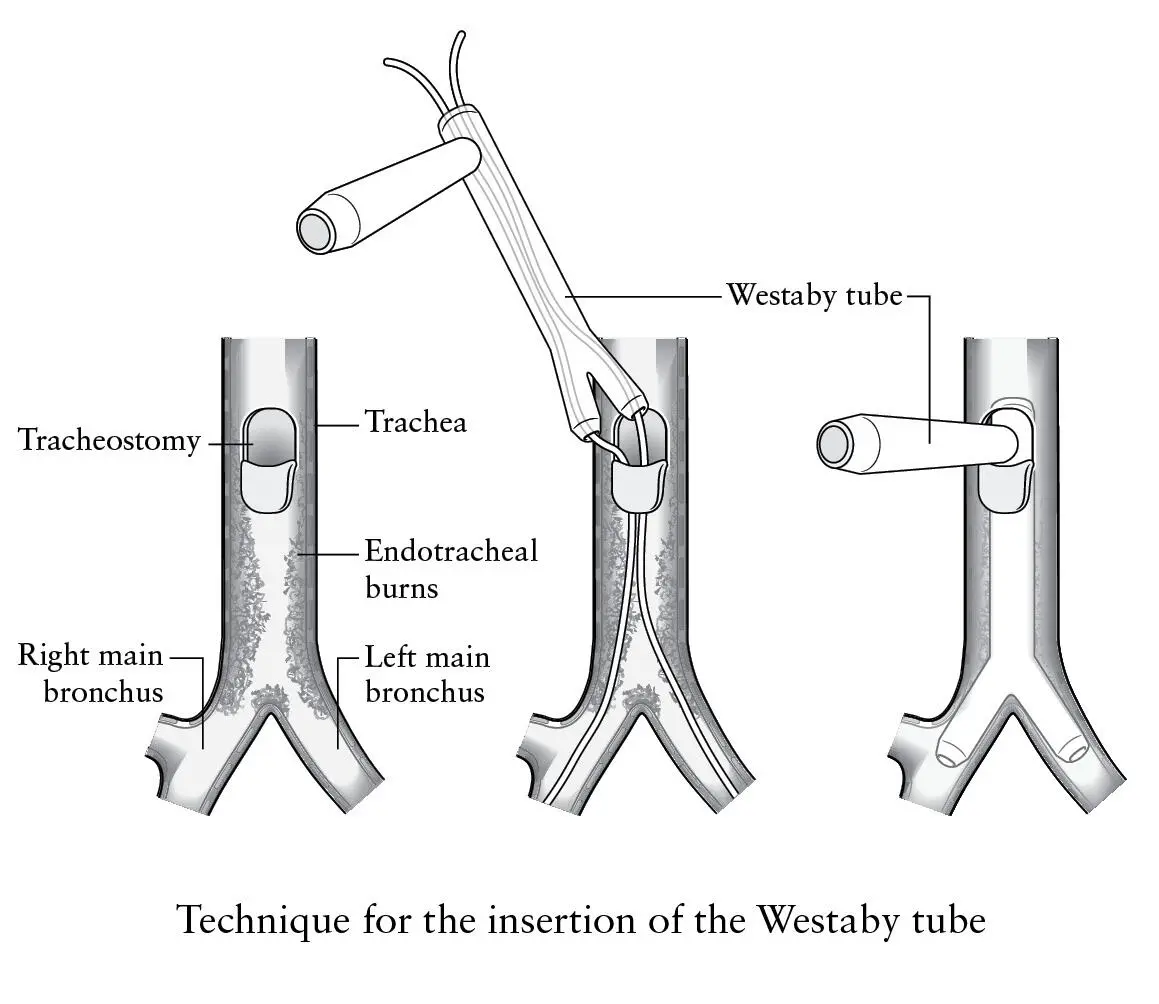

Ever the optimist, I questioned whether there was anything else we could do. Could we make a branched tube to bypass the damaged airways? The boss thought not, because it would clog with secretions. Surely someone else would have done it before for cancer. Then something else occurred to me – a company called Hood Laboratories in Boston, Massachusetts made a silicone rubber tube with a tracheostomy side limb, called a Montgomery T-tube after its ear, nose and throat surgeon inventor. Maybe I should talk to them and explain the problem.

When I bronchoscoped Mario later that afternoon I took measurements to calculate how long the tube needed to be to reach down each main bronchus, and in the evening I rang Hood. A small family firm who were most helpful, they confirmed that no one had tried such an approach but agreed to make me the bifurcated tube to fit the whole of Mario’s trachea and main bronchial tubes. I said we needed it urgently. They delivered in less than one week, with no invoice, pleased to help with this unique case. Now I had to work out how to get it in.

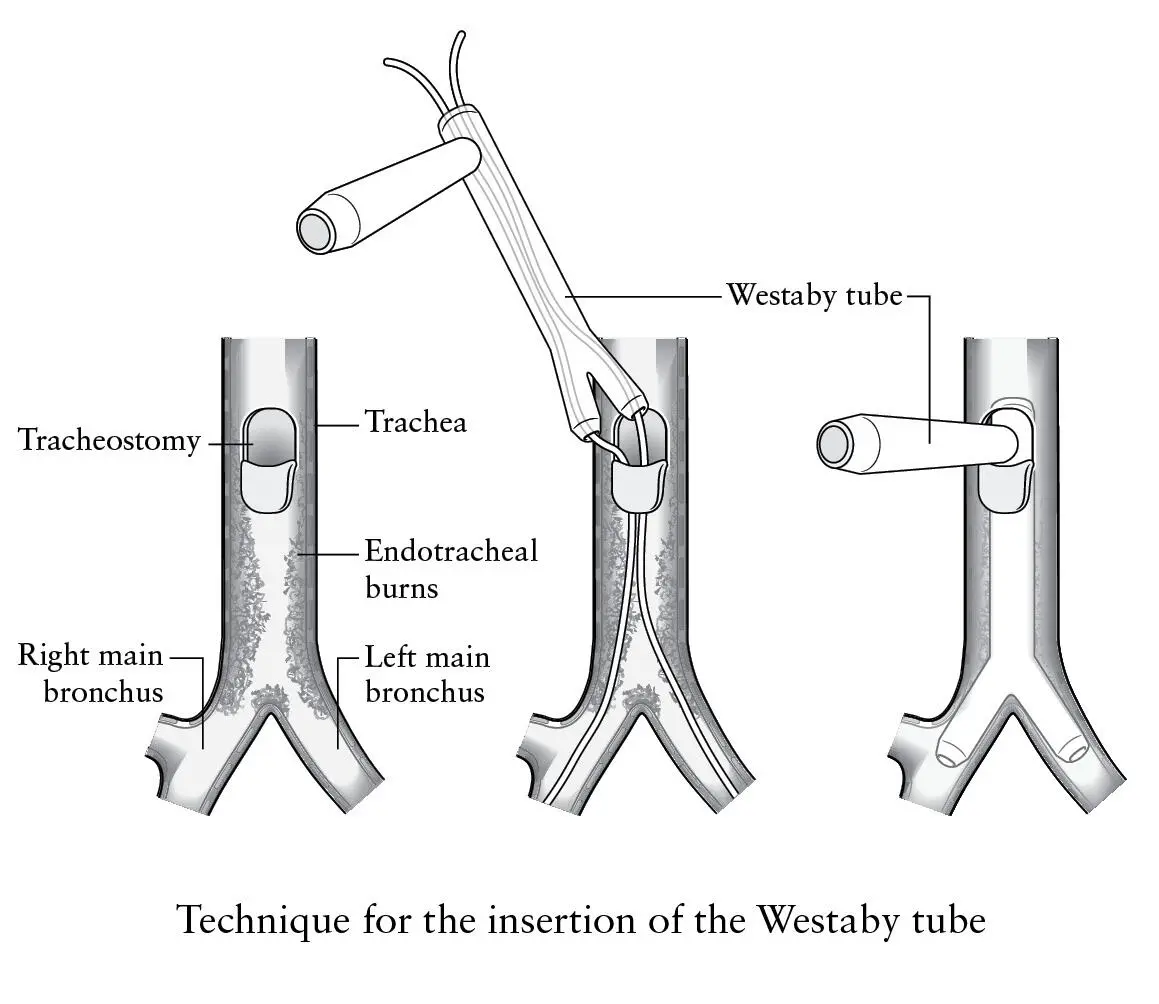

I’d need to railroad the branched end of the tube into the separate bronchi simultaneously over guide wires. But wires were too sharp and dangerous for the delicate silicone rubber, and I needed something blunt and harmless to do the job. We used to dilate strictures of the gullet with gum elastic bougies. Two of the narrowest bougies would fit down the T-Y tube, and down each limb of the Y branches. I could insert the bougies through the damaged trachea and into one bronchus at a time, then railroad the tube into place over them. I drew the technique step by step and showed it to the other thoracic surgeons. The consensus was that we had absolutely nothing to lose. Without some crazy new approach Mario was definitely going to die.

The following day we took him to theatre, removed the tracheostomy tube and inserted the rigid bronchoscope through his burnt larynx. I tried to create as little bleeding as possible this time. We surgically enlarged the tracheostomy hole through which the T-Y tube would be introduced, then the bougies were inserted into the right and left main bronchi under direct vision through the scope, vigorously ventilating with 100 per cent oxygen between each step. So far so good. I lubricated the silicone rubber with K-Y jelly and shoved the tube forcefully downward. The bronchial limbs spread out at the branching point until there was resistance to any further pushing. It was in. Better than sex. The boss took a leap of faith and withdrew the bronchoscope into the larynx.

Ever the Irishman he exclaimed, ‘Crikey, look at this! You’re a bloody genius, Westaby.’ The horribly disintegrating trachea had been replaced by a clean white silicone tube, the Y limbs sitting in perfect position. There was no kinking or compression, and clean healthy airways lay beyond.

Meanwhile Mario was blue and hypoxic. We were all so excited that we had stopped ventilating him, so we needed to blow in oxygen furiously. But he was now easy to inflate through the wide rubber airways. It was a complete revelation. Whether it would last we didn’t know, and only time would tell. It depended entirely upon whether Mario was strong enough to cough secretions out through the tubes, and on our ability to suck them out and ventilate him through the side limb. When the swelling in his larynx and vocal cords subsided we’d keep this closed with the rubber bung. Then he could breathe and speak through his own larynx if it ever recovered. There were many unknowns, but for now Mario was safe. He could breathe. Fifteen minutes later he woke up with fantastic symptomatic relief.

I should have been thrilled that the concept had worked but I wasn’t. I was in a difficult head space. I had a beautiful baby daughter – Gemma – whom I didn’t live with. I lived at the hospital. This was grinding away at me in the background, so I compensated by operating fanatically on everything that I could lay my hands on. I was always available but was possessed by a disquieting restlessness.

In the meantime Mario recovered well, though life was difficult without a voice. He could cough secretions through the tube and keep it clear – something that everyone else had regarded as impossible – and was sent home to his family in Italy. Gratifyingly Hood started to manufacture the T-Y stent and called it the ‘Westaby tube’. We used it often for patients in whom lung cancer was threatening to occlude their lower airways, relieving the dreadful strangulation that my grandmother was forced to endure. Why could no one have done it when she needed help and I was so miserable?

I never knew how many Westaby tubes were manufactured but it stayed in Hood’s product list for many years. My original drawings were published in a chest surgery journal and served as the guide for others. While I still performed thoracic surgery I continued to use it for complex airways problems, often on a temporary basis until radiotherapy or cancer drugs caused the tumour to shrink. It was my grandmother’s legacy. Then came the rare opportunity to use the artificial airways alongside my expertise with the heart–lung machine.

In 1992 I was invited to Cape Town for a conference to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the world’s first heart transplant by Christiaan Barnard. At that meeting the distinguished children’s heart surgeon Susan Vosloo asked me to see a sick two-year-old who’d been a patient at the Red Cross Children’s Hospital for several weeks. Little Oslin lived in a sprawling Cape Town ghetto situated between the airport and the city, acre upon acre of tin shacks, wooden sheds and tents with brackish water and little sanitation. Nevertheless he was a cheerful little chap whose toys were oil drums, tin cans and pieces of wood. He knew no other life.

One day his family’s faulty gas cylinder exploded in the shack, setting fire to the walls and roof. The blast killed Oslin’s father outright, while Oslin sustained severe burns to his face and chest. Worse still, he inhaled hot gas from the blast, much like Mario. The accident department at Red Cross saved his life, intubating and ventilating him before he asphyxiated, then treating his burns with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. The little lad could survive the external burns, but his burnt-out trachea and main bronchi were life threatening, and without repeated bronchoscopies to clear slough and secretions he was destined to asphyxiate. On top of this his face was badly disfigured, he was almost blind and he couldn’t swallow food, just his own saliva. So he was fed with liquids through a tube directly into the stomach.

It so happened that Susan had read a journal article about Mario and the tube I’d designed, and, although Oslin was much smaller, she wondered whether we could do anything to help him. When I first met the lad he was wearing a bright red shirt, had tight, curly black hair, and was pushing himself around the ward on a kiddies’ bicycle with his back to me. Susan called to him and he turned around. The sight of his face took my breath away. There was no hair on the front of his scalp and no eyelids, just white sclera and a severely burned nose and lips. His neck was webbed from contracting scars with a tracheostomy tube in the middle. And the noise coming from him was heart-rending, a kind of rattling with thick mucus secretions made up by a long, noisy in-drawing of breath then a high-pitched wheeze as he forcibly exhaled. It was worse than a horror movie and tragic beyond belief. My first thought was, ‘Poor kid, he should have died with his dad. It would have been much kinder.’

Читать дальше