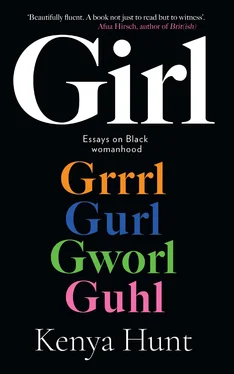

Kenya Hunt - GIRL

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kenya Hunt - GIRL» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:GIRL

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

GIRL: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «GIRL»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

GIRL — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «GIRL», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And while studies and polls reveal a loneliness epidemic sweeping through a generation of millennials thanks to social media, it’s impossible to ignore how Black Twitter, Instagram and Facebook have heightened a sense of community, connectivity and solidarity for an entirely different demographic, particularly Black people and especially Black women.

In my case, the alternative network I found on social media helped soften the culture shock of moving to a new country until I could find my own tribe on the ground IRL.

As a transplant to the UK, navigating insular, impenetrable circles in publishing and fashion, I have often felt the isolation of life as an Only in a way I hadn’t necessarily Stateside. Back home, during my childhood in Virginia and twenties in New York, if I was an Only in the classroom or at work, the extensive tribe of girlfriends I had outside of it all helped fortify me against any feelings of exclusion.

Not to mention I could wake up in Virginia or New York, walk out the door and dive into any variety of enriching Black experiences according to whatever mood I so happened to be in that day. This was something I took for granted, until I moved to London where I found myself in the position of outsider more than not.

In the UK, where I had moved in the late aughts into a historically white, working-class south-east London neighbourhood in the throes of gentrification, I found myself seeking out sameness, in any form, as a reprieve from Otherness. I knew the city had a rich Black cultural scene, I just hadn’t discovered how or where to tap into it just yet. During those first six months here, I lived alone waiting for my boyfriend (who is now my husband, and, I should point out, an American mix of Irish and Italian) to tie up loose ends back in the States so that he could board a plane in order to move in with me.

I craved the company of other Americans, people who shared my accent and colloquialisms, people who didn’t pepper their spellings with u’s or say ‘sorry’ instead of ‘excuse me’ as they attempted to navigate crowded pubs and rush hour trains. I formed tight, if fleeting, bonds with people I would have probably never gravitated toward back home in the States, over the smallest Americanisms: a guilty affinity for Chick-fil-A and Ben’s Chilli Bowl or subscriptions to The New Yorker and New York magazine. It didn’t take much.

But more than anything, I craved a sense of community with other Black people, specifically Black women, and especially as Black people throughout the diaspora revelled in a new wave of pride and consciousness in the wake of the Obama presidency. I had grown up the product of institutions built to strengthen Black people in the face of systemic discrimination, the child of two graduates of historically Black universities. I understood the power in a strong tribe. And I knew if I was to successfully live in another country, I needed to find a community, even if it meant building one myself. I longed to be in a room where I was one of a loud, rambunctious many — like the greatest of all Black block parties, Sunday dinners, cookouts or family reunions — rather than just the contained, observant party of one.

In the meantime, social media met the need, connecting me with my extended sister circle back home as well as a group of talented Black women writers, early generation bloggers and editors in other cities around the world who I got to know through the Internet. Social media was the thing that tided me over until I could find what I was looking for offline.

I had found small pockets of it in London. At my first Notting Hill Carnival. At the dinner party of a cousin of a friend’s friend later that autumn. And at a string of Afro hair salons I tried. But it wasn’t until January 2010 that I finally found what I had been looking for on a larger scale.

A friend, determined to show me that London was just as rich in community and melanin as New York (her words: ‘if not even more so!’), had invited me to be her plus one for an art party. The Tate Britain had just launched a sprawling, mid-career retrospective of the British painter Chris Ofili’s work. Chris Ofili, unapologetically Black and Manchester born, of Nigerian descent. Chris Ofili, Turner Prize-winning member of the famed YBAs. Chris Ofili, the man behind that painting of the Madonna rendered as a Black woman surrounded by big, Black, sexualised asses and actual elephant dung on canvas. The one that offended not just Catholics the world over, but divided the art world and pissed off a fair proportion of the viewing public. The one the mayor of New York tried to ban. Yeah, I’ll be there.

It was the Blackest party I had ever been to in London so far, not quite a sea of melanin, but definitely more Black faces than I had seen in a single gathering thus far, beyond my semi-regular trips to Brixton for hair supplies and goat curry. It was 5 February and damp and glacial outside. But indoors, the rooms were warm and the crowd was hot. A DJ played Afrobeat as guests milled around dressed in their finest.

I was buoyed not just by the Blackness in the room — a photogenic mix that included tall, elegant-looking older men in jackets and kente shirts, young, stylish women in clashing graphic prints with all manner of braids and twist-outs, and lean, straight-backed tracksuit-wearing guys with towering, free-growing dreadlocks — but also the Blackness hanging on the walls. Collaged, painted, beaded and gold-flecked odalisques, Black women in regal and sensual repose. A constellation of Afroed heads. Teardrops containing the image of slain Stephen Lawrence. Cut-out images from Blaxploitation films. Ice T. Don King. Blackness was the star, subject and guest of honour at the show.

Near the gift shop, a line snaked its way through the ground floor as guests waited for the artist to sign catalogues and prints.

The mood was celebratory and dazzling. The night felt glamorous, even if much of the work on the walls was haunting and devastating. The evening was a moment and a rarity — a historically white institution and an enduringly homogenous industry honouring the country’s most famous Black artist.

But this was a different era to where we are now. Instagram had launched but #Blackexcellencehadn’t yet taken off as the natural progression from the Black Power Movement, born in the 1960s, it would eventually become. And I hadn’t yet solidified the network of girlfriends I would go on to build following that night — effervescent, ambitious journalists, artists, stylists and executives with thriving careers who not only lived Black excellence but wanted to create space for other women to join them. Women who did make space for other women, building out teams, publishing imprints and brands that created new jobs and platforms. I had finally found my tribe! And the shared experience helped minimise the isolation I felt in my work life.

No, Black excellence hadn’t yet evolved into a social media phenomenon and cultural sea change. But that was where it had reached by the time Marvel’s Black Panther , perhaps the decade’s most definitive visualisation of Black excellence, beyond the Obama White House itself, hit theatres in 2018.

Like the Chris Ofili exhibition, the Black Panther premiere in London had taken place in February. Not that the cold weather stopped anyone from showing up in their boldest, brightest clothes, accessories and African prints. And not since the Ofili exhibition had an unapologetic study and celebration of Blackness generated such fervent excitement among Black folk and the white mainstream alike. Yes, London had hosted the Basquiat retrospective Boom For Real at the Barbican a year before, but that was largely an American show staged in the UK. There was something about the Black Panther moment that, like Ofili’s evening, felt uniquely British with its cast full of homegrown talent filling both the screen (despite being written and directed by Americans) and the theatre.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «GIRL»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «GIRL» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «GIRL» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.