Already the sun was riding low above the cornstalks. The shadows were long, and the whirring of the crickets and grasshoppers had slowed in just the short time she’d been standing at the side of the road. She folded the map, getting it almost right on the first try. She had to find her way to this Riverbend place. And soon. For all she knew it was so small they rolled up the sidewalks at five-thirty and the whole town went home to supper, including whoever ran the filling station. But evidently it was the only town for miles around.

She was so tired. She’d driven most of every night and half the next day for the past four days. She’d gotten into the habit when crossing the desert, because it was cooler driving. But by the time she’d reached the plains of Kansas, she was doing it to save money. Motel rooms were expensive. Even the cheapest, no-frills ones cost more than she could afford. She couldn’t—wouldn’t—arrive at her sister’s home in Albany seven months pregnant, unmarried, and with nothing but the clothes on her back.

I’m going to have a baby in two months. As always, the thought gave her a little shock of anxiety mixed almost equally with joy.

She might have picked the wrong man to be the father of that baby. She might have made a mess of her life in a lot of ways. But she was determined to be a good mother, even if that meant going home to Albany in disgrace, putting up with her older sister’s I-told-you-so’s and going on welfare until the baby was old enough for her to get a job. Even if it meant giving up her dream of teaching history to spend the rest of her life working to keep food on the table and a roof over their heads.

She already loved this baby. She was going to keep it. And she was going to raise it the best way she knew how. But she didn’t dare think too far ahead, because the enormity of it all scared her to death. One day at a time. One step at a time. That was how she’d made it so far. It was how she intended to keep on.

And the very first thing she needed to do was buy gas for her car.

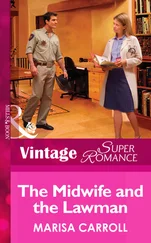

“LOOKS LIKE RAIN,” Ethan Staver said, lifting a finger off the steering wheel to point at the horizon. “Clouds been piling up all afternoon.”

“Radio said it would start before sundown,” Mitch Sterling replied. “Supposed to rain all night and all day tomorrow.”

“That’ll have the farmers on the move.”

Mitch surveyed the fields of yellowing corn that bordered the county highway through the bug-splattered windshield. “None of them like to get bogged down in wet fields.”

“And the longer it takes for them to get their corn in, the later it’ll be before they can take off for Florida for the winter.”

Mitch grinned. Ethan hadn’t lived in Riverbend, Indiana, all his life the way he had, but the police chief knew farmers.

“What did you think of the renovations to the regional jail?” Mitch asked him. They’d spent the afternoon touring the facility—Ethan as the representative of Riverbend’s small police force, and Mitch as a member of the town council.

“The place looks pretty good. Not that we send a lot of people there, but it’s good to know there’s a secure facility when we need one.”

Riverbend was the seat of Sycamore County, Indiana. It had its own jail in the courthouse, but these days it was pretty much just a holding station for prisoners. There was no way the county, or the town, could afford a state-of-the-art facility like the regional jail.

“And the extra revenue we get from renting our unused bunk space to the guys from Indianapolis is a shot in the arm to my budget,” Ethan said.

“Amen to that,” Mitch answered. Keeping the town budget balanced while juggling the needs and wishes of a population bordering on nine thousand was quite a job. Mitch enjoyed being on the council, but he also had his own business to run.

He glanced at his watch.

Ethan noticed. “I’ll have you back at the lumberyard before three,” he said.

“It’s Granddad’s first day back since his hip replacement,” Mitch reminded his friend. “I don’t want him to overdo it.”

“Sam going to the store after school?”

“He’s got an art lesson with Lily Mazerik after school. I told him he could go home from there if I didn’t come to pick him up. He’s at the age where he thinks he should be able to stay alone.”

“He’s what? Ten? Eleven?” Ethan asked.

“Ten going on forty,” Mitch replied. Sam was growing up fast, too fast, Mitch thought some days.

“How’s he doing in school this year?” Ethan wanted to know. Sam was hearing-impaired. He attended regular classes and got good grades, but he worked hard at it. And so did Mitch. He spent a lot of time with Sam’s teachers and his math tutor, trying to stay ahead of any problems.

“He’s off to a good start. But he was really disappointed not making the Mini-Rivermen football team. He had his heart set on the starting-linebacker position.”

“He’s pretty small to be a linebacker.”

“Yeah. And football is one sport where his handicap really holds him back.” Even with his hearing aid Sam couldn’t hear the play calls or the coaches’ instructions. There was no getting around it.

Sam had done pretty well in Coach Mazerik’s summer sports camp, Mitch had to admit, especially at swimming. And he’d played Little League baseball. The trouble was, as Ethan had just pointed out, Sam was small for his age. In football and basketball, his two favorite sports, that was as much of a handicap as his hearing impairment.

“He’ll have a growth spurt in the next year or two, and then watch out,” Ethan said.

That was probably true. Mitch himself had been something of a runt, the shortest in his group of friends until nearly eighth grade. And then he’d shot up six inches in a year. Maybe it would be that way for Sam, too. He wanted to see his son get as much fun and satisfaction out of playing school sports as he had.

Ethan’s scanner squawked into life, interrupting Mitch’s thoughts.

They both listened for a moment or two as the dispatcher and another disembodied voice discussed the status of the jackknifed rig ahead of them on the highway. “Sounds like the state boys are handling it just fine,” Ethan said. “No need for me to get involved.” He flipped on the cruiser’s turn signal and headed off onto a county road that ran into the outskirts of Riverbend near the golf course. “We’ll make better time this way.”

Five minutes later they topped a low rise that brought a fleeting view of the Wabash winding away toward the west. The sky was blue, darkening to almost black on the horizon. The trees were shades of gold and yellow and brown, with a splash of maple red and the near purple of sumac here and there. Mitch could see tractors and combines working in half-a-dozen fields before they disappeared behind rows of unharvested corn.

Ahead of them a small red car was parked on the side of the road. A woman was standing outside it, looking at something spread out on the hood. She was wearing a long denim jumper and a pink blouse. Her hair was blond and shoulder-length, but since her back was to them, it was hard to pick out any further details.

“That’s an out-of-state plate—can’t quite make it out, though,” Mitch commented.

“California,” Ethan replied tersely. His eyesight was evidently sharper than Mitch’s.

“Suppose her car’s broken down?”

“Could be.” Ethan turned on his emergency lights, but not the siren, and slowed as he approached the car.

Mitch saw his friend’s lips tighten. He couldn’t see Ethan’s eyes behind his mirrored sunglasses, but he knew they would be steady and gray. Ethan was an ex-army Green Beret and all cop. The woman standing beside her car was probably perfectly innocent of any wrongdoing. But until Ethan proved that for himself, he wouldn’t let down his guard.

Читать дальше