‘Concerns from a moral or ethical standpoint [regarding war against Iraq] are a personal matter,’ it acknowledged. Worries shouldn’t be kept to oneself. Anyone having reservations about what they were asked to do should contact the Welfare Office, the staff counsellor, or one of three specifically named senior officers. No, she thought. A slow-moving, red-taped, and supremely protective bureaucracy was not the answer.

Unwritten, but clear in its intent, was a warning to GCHQ staff. And that was what was keeping her awake.

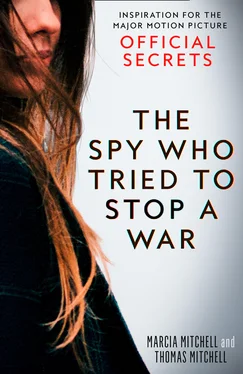

CHAPTER 3: Four Weeks That Changed Everything

More of a concern to us was that we would be joined in the prosecution. To publish is an offence under the Official Secrets Act as well. We were as culpable as Katharine. But they’re cowards. So they preferred to take on the little guy – in this case, little woman – rather than us big guys.[1]

– Martin Bright, Observer editor

What I hoped was that people would see what was happening and be so disgusted that nobody would support the war in Iraq. And if anybody would go to war it would be the United States going it alone. And I even hoped that the US general public would somehow realize that they were being dragged hook, line, and sinker into the war.

– Katharine Gun, to the authors

AN UNSUSPECTING YASAR drove his wife to work on Monday morning, stopping at the GCHQ gate long enough to give her a quick squeeze and a kiss before reaching across to open the passenger door for her. She gave him a smile, climbed out of the car, and stood watching until the red Metro was out of sight. As she turned to enter her secret world, she felt transparent, as if everyone around her would see through her and into her. Would see the pounding heart and knotting stomach. Would see into her mind and be appalled by the conspiracy of her thoughts.

The final decision to act had been made. When? She wasn’t certain. Possibly in those first few minutes on Friday, when Koza’s message appeared on her screen. Perhaps during the solitude of her walk to the café to meet Yasar after work, or while talking with Jane later. At some point, there was no emotional turning back. More likely, it had been there, the finality of it, after her talk with Jane.

‘This morning, Monday, I worked in a different office from the one I normally worked in, so I thought it would probably be a good idea to print a copy off from that computer, rather than the one that was my normal terminal. Obviously, this is all an indication of how I was trying to remain as anonymous as possible. I brought up the e-mail, looked at it one more time, then copied it and pasted it to a different window. I printed it off and put it in my handbag. Of course, if I were caught, that’s where anyone would look, wouldn’t they?

‘I was planning to take the e-mail outside GCHQ’s grounds, which is already breaking the law, regardless of whether or not you make it public. You weren’t, without prior permission, permitted to take classified documents off GCHQ territory. I knew exactly what I was doing.’

Up to this point, it is true that Katharine had broken no law. Once she removed the copied document from the premises, which she fully intended to do, she could be charged with high crime against her country. The thought made her ill, and throughout the day she reminded herself that this was something right, that she was not a criminal. What she was doing, however, identified her as precisely that.

‘I guess some people would accuse me of being naïve, in that I didn’t consider the ramifications of what this act would be for me personally. And that’s probably true, in the sense that I’ve never done anything really bad. I mean, I had never done anything that could be considered a crime. It made it very difficult to consider what I was doing as a criminal offence. In fact, it felt like it was the only morally right thing to do. Oh, I was of course frightened and nervous, but – and it’s hard to explain – I didn’t feel frightened or torn apart by my decision, once it was made.

‘So, call me naïve if you will, but obviously if I’d been selling state secrets to somebody considered to be an enemy, an arch-rival, that would be a totally different issue. If I had been leaking information not in an attempt to prevent unnecessary loss of life, that would have been different. There are degrees of breaches of official secrecy, and I didn’t feel that mine was a criminal offence. I believed I was doing the right thing.’

The following day Katharine posted Koza’s message to Jane. When it arrived, Jane read the words that had so distressed Katharine and decided to pass it along as agreed. Had she known what was to come later, Jane might well have destroyed the message the minute it reached her. But she did not know, and she felt confident that her friend Katharine would not betray her, that she would not be considered a co-conspirator.

By that Monday morning when Katharine was printing Koza’s message, other recipients were responding in quite a different way. It is assumed that Sir Francis, in his last two months as the head of GCHQ, responded both favourably and immediately, authorizing cooperation with the NSA. According to sources close to the intelligence services, the US request for UK cooperation was indeed ‘acted on’ by the British.[2]

At the time Koza’s request arrived in the United Kingdom, there were at least some intelligence and other government officials asking critical questions, secretly of course, about the legality of an invasion. The whole business was sticky, and it seemed fairly obvious that the United States was asking for help not only with electronic black bagging, but also with what could become high-stakes political blackmailing.

At the very highest level, it already was known – and had been since April 2002, when Blair and Bush met in Crawford, Texas, and reached an accord for military action – that the rhetoric coming from the White House and Downing Street was only that.[3] The decision to invade Iraq had been made, pushed by George Bush and his neoconservative team. It was now essential to find an excuse, an acceptable rationale for doing so. Twisting the arms of the recalcitrant UNSC representatives in order to win approval for a new resolution could supply a universally acceptable rationale. If regime change came about as a result of invasion based on a WMD threat, well, that would be serendipity within the rules. Thus in some lofty quarters, where the strategy was either known for certain or even ‘twigged’, there was neither shock nor surprise when the Koza message arrived at GCHQ.

‘For four weeks I was nervous, on edge. Every day I frantically searched the papers and watched the news. I figured it would take a few days to appear, but then, day after day, there was nothing. It was difficult trying to live normally, as if nothing had happened. It was a struggle, I mean, going about life that way. Everything was quiet, for those four weeks, and I began to think that perhaps it wasn’t actually of interest to anybody. Perhaps it would never be made public. I suppose I was a little bit relieved. I could go on with my life as before, and everything would be the same.

‘No one would know what I had done.’

The news that Katharine was reading during this period showed an intense ratcheting up of the pitch for war. Three days after she posted her letter to Jane, Colin Powell went before the United Nations – and the world – to explain why war was absolutely necessary, that Saddam Hussein had stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction ready to destroy his neighbours and threaten the peace and security of everyone everywhere. Details about the kind and numbers of weapons known to be in Iraq’s possession were supplied. And he was convincing, this highly respected member of the Bush administration. Handsome, charismatic, articulate, respected – no one else in the Bush administration could have done the job so masterfully.

Читать дальше