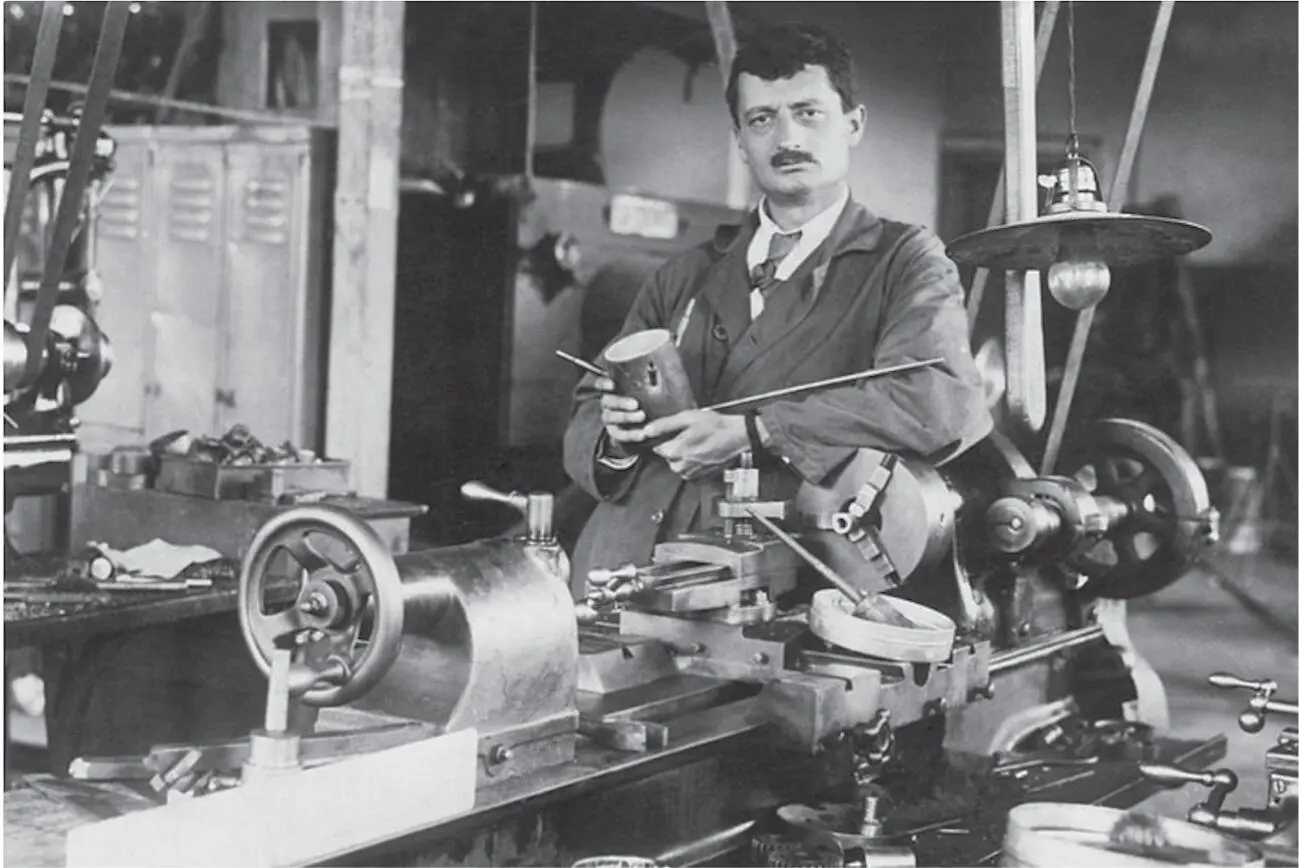

A full decade after Tsiolkovsky’s groundbreaking paper, in 1913, a French aircraft designer named Robert Esnault-Pelterie independently published his own version of the rocket equation. But once again few took notice. In the United States, Robert Goddard, the second of the three pioneers of rocketry and a part-time instructor and research fellow at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, was quietly conducting his own rocket research. Entirely unaware of Tsiolkovsky or Esnault-Pelterie, he submitted patent applications for both a liquid-fueled rocket and a multi-stage vehicle.

Like Tsiolkovsky, Goddard had also experienced social isolation during his formative years. A frail only child, he was kept out of school for extended periods due to ill health. As a result, he didn’t graduate from high school until age twenty-one. During his solitary time at home he read stacks of books from the local library, particularly volumes from the science and technology shelves. He also read H. G. Wells’s science-fiction classic The War of the Worlds, which made a lasting impression. At age seventeen in 1899, while aloft in the branches of a cherry tree on his family’s New England farm, Goddard experienced an epiphany that moved him so deeply that he noted the date on which it occurred. “As I looked towards the fields at the east, I imagined how wonderful it would be to make some device which had even the possibility of ascending to Mars. I was a different boy when I descended the tree from when I ascended for existence at last seemed very purposive.”

© NASA

Clark University professor Robert Goddard, who in 1926 launched the world’s first liquid-fueled rocket from a farm in Auburn, Massachusetts. Throughout most of his career he revealed few details about the progress of his research. However, spies in the United States working at the behest of the Soviet Union and Hitler’s Germany attempted to breach Goddard’s wall of secrecy.

During World War I, while teaching at Clark University, Goddard obtained research funding from the War Department for an experimental tube-launched solid-fuel rocket rifle, an early version of what would become the bazooka. He also proposed a rocket that could ascend seventy miles into the atmosphere and carry high explosives or poison gas at least two hundred miles. But after the Armistice, no American military officials thought long-range missiles a subject worthy of further research, so Goddard sought to find support elsewhere.

It was a technical paper funded and published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1920 that suddenly placed Goddard’s name on newspaper front pages around the world. “A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes” proposed that a rocket could be used for the scientific exploration of the atmosphere, placing artificial satellites into orbit, aiding weather forecasting, and physically hitting the Moon. His paper made no mention of human space travel to the Moon; however, many newspaper reports heralded his study with dramatic headlines implying Goddard was working on a moon rocket that would transport human passengers.

Within weeks, The New York Times announced that a twenty-four-year-old pilot of the New York City Air Police had willingly volunteered to be the first person to fly to Mars. Concerned that the United States must maintain its position with other nations in the air, Captain Claude Collins said he would ride the world’s first interplanetary rocket, provided a ten-thousand-dollar life-insurance policy was part of the arrangement. The Times treated Goddard somewhat less admiringly than it did Captain Collins when it published a scathing editorial taking the college professor to task for believing that a rocket would function in the vacuum of space. The Times slammed Goddard, claiming he was unfamiliar with basic Newtonian physics and showed a “lack of knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.” His pride wounded, Goddard soon grew wary of the popular press. Sensational stories about the American professor’s forthcoming moon-rocket flight continued to appear in publications around the globe throughout the early 1920s. And occasionally Goddard was complicit, supplying dramatic quotations apparently intended to entice potential investors, such as his plan for a giant passenger rocket capable of crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a few minutes.

However, when Goddard actually made history with the world’s first successful launch of a liquid-fueled rocket on March 16, 1926, in Auburn, Massachusetts, no journalists were present, and no account appeared in contemporary newspapers. The date is now celebrated as the dawn of the space age, but for most of his career Goddard carefully guarded information about his research, afraid that others might steal his secrets and profit from his work.

THE SENSATIONAL ATTENTION accorded Goddard’s Smithsonian paper appeared in the European press just as the third of the trio of rocketry pioneers, a former medical student from Austro-Hungaria named Hermann Oberth, was readying his work for academic review. Born in 1894, Oberth was a brilliant student of mathematics and had been fascinated by the idea of spaceflight since age twelve, when he committed to memory passages from Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon. Oberth had tried to interest military strategists in a proposal for long-range missiles during the First World War, but his paper went unread. After the war he revised his work, this time focusing on the basic mathematics underlying space travel. However, when he submitted the paper as his doctoral dissertation, it was rejected as “too fantastic.”

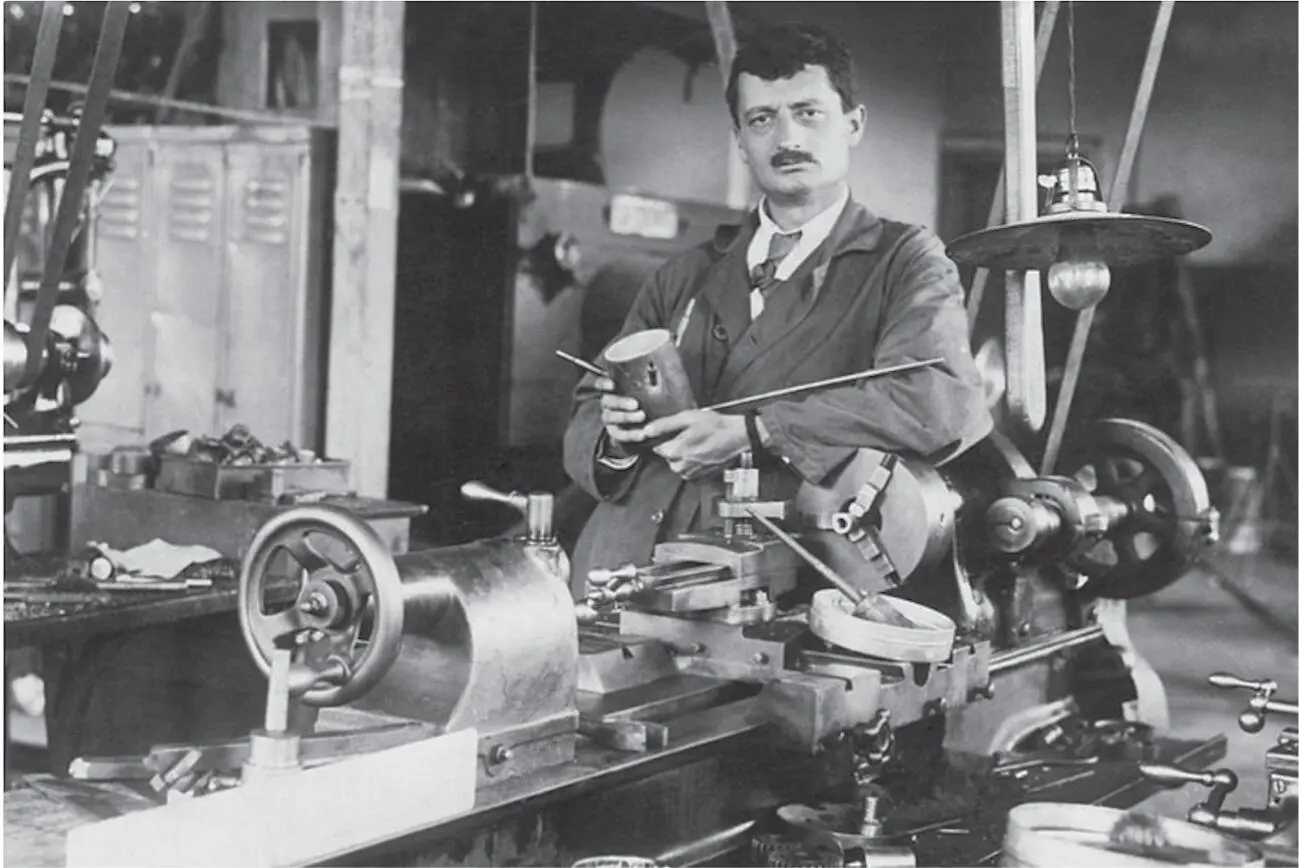

© Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM 87-5770)

Hermann Oberth photographed in his workshop while assisting on the production of the German science-fiction feature film Woman in the Moon. When he was ten years old, the telephone and the automobile first appeared in his rural hometown. In his later years he witnessed the launches of Apollo 11 and the space shuttle Challenger.

Undeterred, Oberth obstinately continued to pursue his studies independently, dismissing his instructors as unworthy to judge his work. For this gifted mathematician, formulating the necessary calculations for space travel was a diverting intellectual exercise that gave him a sense of ownership and agency. “This was nothing but a hobby for me,” he said, “like catching butterflies or collecting stamps for other people, with the only difference that I was engaged in rocket development.”

He asked himself a series of questions that would need to be answered if humans were to enter outer space: Which propellant should be used—liquid or solid? Is interplanetary travel possible? Can humans adapt to weightlessness? How might humans nourish themselves in space? Can humans wearing space suits venture outside vehicles? In contrast to Goddard’s more cautious approach, Oberth embraced the unknown by posing imaginative questions prompted by his reading of science fiction. He then devised practical solutions founded on his mathematical and engineering expertise.

In 1923 he published a short technical version of his dissertation, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Space), personally paying the expense of the book’s entire printing. Fortunately, his vanity-publishing project was a wise decision. By issuing the book in German, which in the early twentieth century was the dominant language of the scientific community, Oberth established himself as the world’s leading theorist of human spaceflight, overshadowing the more reclusive Goddard. When he read the German monograph, Goddard believed Oberth had borrowed his ideas without proper attribution, though there is little evidence to support his suspicions.

Читать дальше