Von Braun signed with a speakers’ bureau and commanded as much as two thousand five hundred dollars for an appearance. Columbia Pictures and a West German studio commenced discussions to determine whether his personal journey from Nazi weapons engineer to Cold War American hero might serve as the basis of a successful dramatic film.

The attention and adulation given von Braun and his Huntsville team neglected one important German without whom Explorer would never have orbited. Hermann Oberth had joined the German rocket community in Huntsville, after von Braun had reached out to his former mentor and offered him work in the Army Ballistic Missile Agency’s research-projects office. But Oberth hadn’t been able to stay current with the ever-changing technology, and as a German citizen, he was restricted from reading classified information. He worked alone on projects of his own design, but his research produced little of consequence. Oberth’s prickly personality didn’t help. He felt out of place in Huntsville and in the United States and harbored resentment for some of his former colleagues, who he believed had betrayed him.

The Army also had reasons to avoid bringing attention to the mentor of the world’s most famous rocket designer. Oberth was notorious for making provocative or controversial remarks. He might, for instance, insist with icy certitude that at age sixty-four he should be chosen as an astronaut. “They should send old men as explorers. We’re expendable.” Or he might try to argue why Hitler “wasn’t all that bad” or explain how if Germany had won the war Hitler would have funded space travel more vigorously than either the Soviets or the Americans.

And then there were the UFOs. By the mid-1950s Oberth had announced that the rash of UFO sightings indicated that Earth was being visited by extraterrestrials. He appeared at UFO conferences and expounded with deadly seriousness about the lost continent of Atlantis and its connection to Germany.

So when he reached the mandatory retirement age of sixty-five, few in Huntsville objected to his decision to collect his pension back in Germany. Oberth announced he would devote his time to philosophy. “Our rocketry is good enough, our philosophy is not.”

VON BRAUN’S TRIUMPH with Explorer did little to rectify the ongoing competition among the different branches of the armed forces. Former defense secretary Wilson’s decision two years earlier to give the Air Force responsibility for long-range ballistic missiles implied it would become the branch designated to oversee any future military activities in earth orbit. However, von Braun and General Medaris at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency continued to work on their own ambitious ideas, including plans for a large heavy-lifting rocket that could place human-piloted vehicles in orbit.

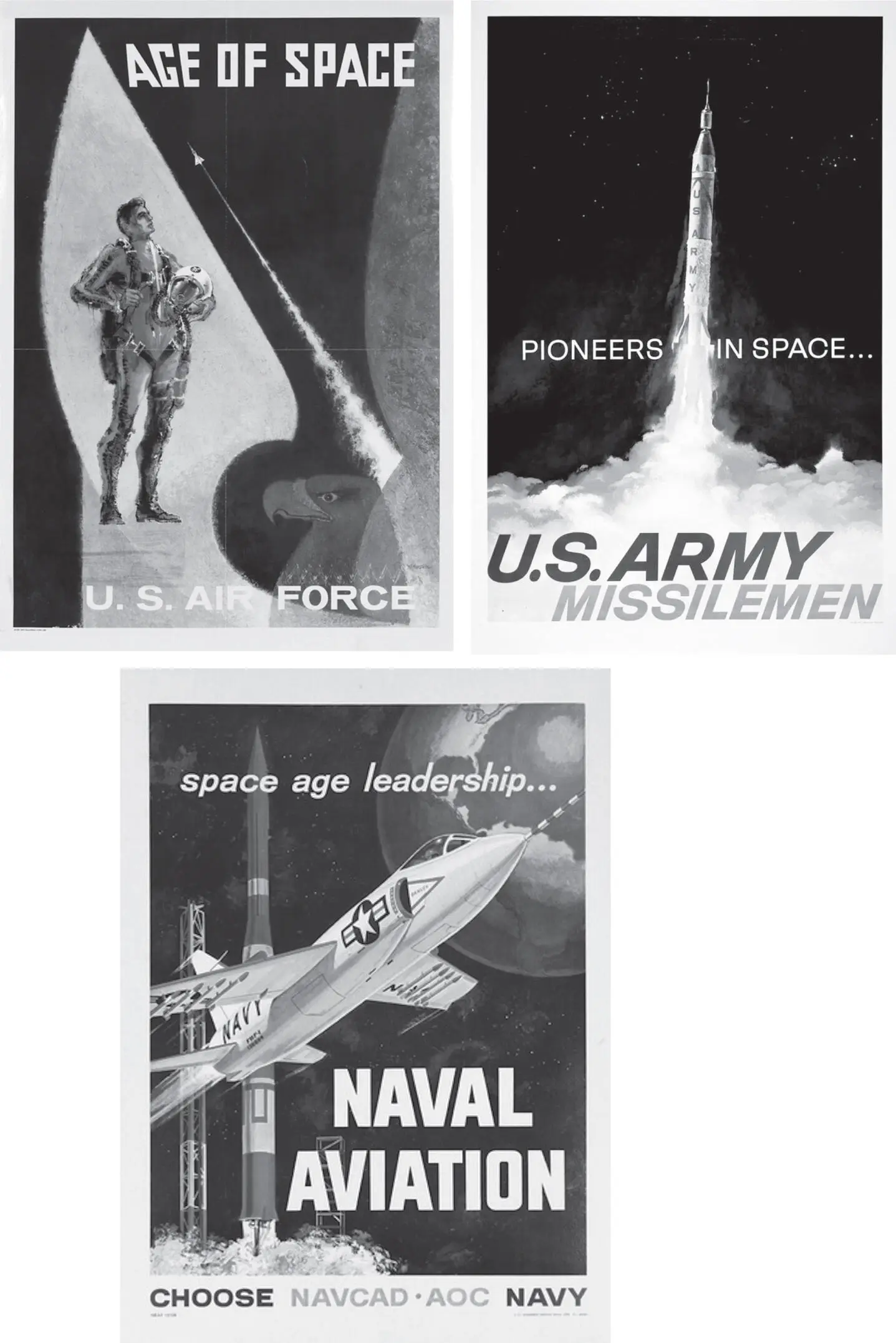

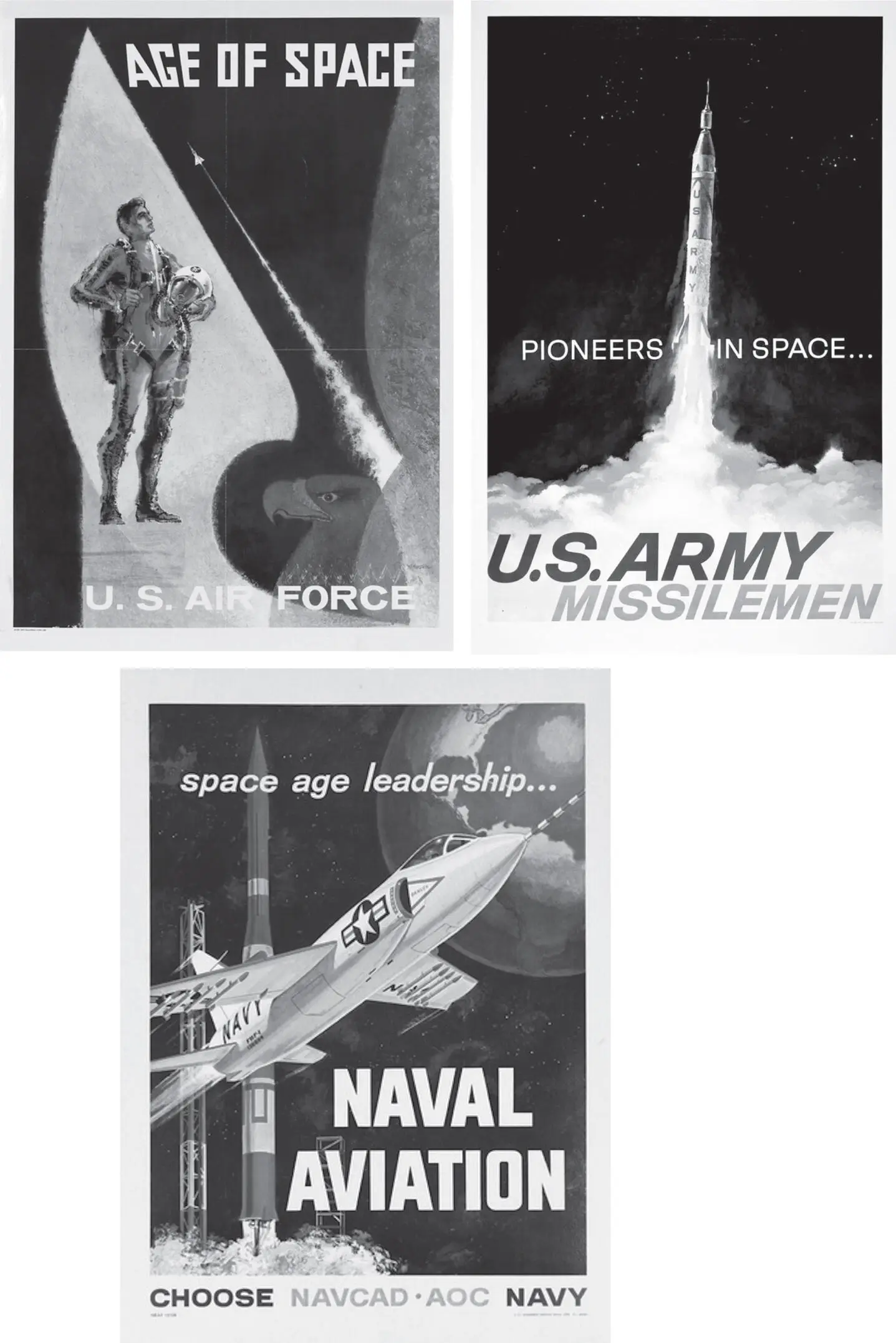

The ongoing competition extended into the services’ public marketing campaigns, with the Army, Air Force, and Navy each promoting their leadership in the dawning space age. The Navy regarded space as a new ocean to conquer and command, in keeping with von Braun’s allusion to the great maritime powers of the past. The Air Force argued that space was an extension of the conquest of the air, just at a higher altitude, and coined its own marketing term, “aerospace.” And the Army, while regarding rocketry as a high-powered extension of the artillery, also used the launch of Explorer to promote itself as the team that got things done.

Shortly after Sputnik and the panic on Capitol Hill, the Air Force inaugurated its own piloted spacecraft program, called Man in Space Soonest. Its Special Weapons Center even commissioned a top-secret fast-track study, code named Project A119, to evaluate the scientific paybacks of Fred Singer’s proposal to explode thermonuclear weapons on the Moon, an idea some in the Air Force believed would demonstrate to the world America’s military prowess and instill patriotic pride at home.

© Recruiting posters (Public Domain, private collections)

By the late 1950s, the Army, Navy, and Air Force were each employing space age–themed marketing campaigns to encourage new recruits. The Army’s poster celebrates the launch of Explorer I, the Navy’s includes a picture of Vanguard, and the Air Force promotes its plans for a human military presence in outer space.

President Eisenhower realized he needed to resolve the ongoing service rivalry that was becoming counterproductive and costly to the country. He was also increasingly wary of the power of some personalities in the American military to influence public opinion and gain congressional backing for their ambitious and expensive projects. Accordingly, Eisenhower decided to reduce the military’s role in future human spaceflight by signing into law the National Aeronautics and Space Act. His announcement in late July 1958 followed a Presidential Science Advisory Committee that recommended developing space technology in response to the “compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before.” It was a declaration that—when slightly reworked with the adverb “boldly” in the prelude to the television series Star Trek eight years later—would become one of the most familiar catchphrases of the latter half of the twentieth century. Presciently sensing the emotions those words would invoke, Eisenhower noted in an accompanying letter, “This is not science fiction … every person has the opportunity to share through understanding in the adventures which lie ahead.”

The National Aeronautics and Space Act created a new civilian space agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), built in part from the half-century-old National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which was already dedicating half its resources to space-related projects, including Vanguard and the X-15 suborbital space plane. Chosen as NASA’s first administrator was the president of Case Institute of Technology, T. Keith Glennan, a former member of the Atomic Energy Commission.

Within the first week of NASA’s creation, the Air Force terminated its nascent Man in Space Soonest initiative. NASA would now oversee a new civilian-run program, named Project Mercury, dedicated to putting the first Americans into space. Instead, the Air Force would concentrate on its own piloted winged space glider, known as Dyna-Soar, which, after being launched on top of a ballistic missile, would allow military crews to service satellites, conduct aerial reconnaissance, and possibly intercept enemy satellites.

Despite the idealistic rhetoric about exploration and adventure, it was impossible to conceal the reality that the civilian agency planned to send Americans into space atop repurposed military missiles developed to deliver warheads and transport reconnaissance spy satellites. The United States therefore chose to emphasize the open, peaceful, and cooperative nature of its civilian space program, which stood in contrast with the secretive and militarily aligned Soviet effort.

Remarkably, the Soviet Union had never placed a high priority on launching the world’s first artificial satellite. Rather, its military rocket program had been developed to inform the world that Russia had the capability to strike other nations with nuclear weapons. Sputnik was an unexpected dividend after von Braun’s Soviet counterpart, Sergei Korolev, developed a heavy-lifting rocket—the R-7—capable of delivering a six-ton nuclear warhead. But the Soviet warhead turned out to be far lighter than the original estimate; Korolev had designed a rocket much more powerful than needed.

Читать дальше