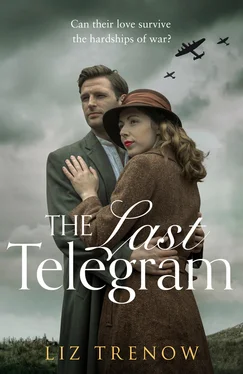

LIZ TRENOW

The Last Telegram

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2012

Copyright © Liz Trenow 2012

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2020

Cover photograph © CollaborationJS/Trevillion Images

Liz Trenow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007480821

Ebook Edition © February 2020 ISBN: 9780007480838

Version: 2020-02-14

In memory of my father, Peter Walters (1919–2011), under whose directorship the mill produced many thousands of yards of wartime parachute silk. All of it perfect.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Epilogue

Book Club Q&A for The Last Telegram, by Liz Trenow

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Liz Trenow

About the Publisher

The history of silk owes much to the fairer sex. The Chinese Empress Hsi Ling is credited with its first discovery, in 2640 BC. It is said that a cocoon fell from the mulberry tree, under which she was sitting, into her cup of tea. As she sought to remove the cocoon its sticky threads started to unravel and cling to her fingers. Upon examining the thread more closely she immediately saw its potential and dedicated her life thereafter to the cultivation of the silkworm and production of silk for weaving and embroidery.

From The History of Silk , by Harold Verner

Perhaps because death leaves so little to say, funeral guests seem to take refuge in platitudes. ‘He had a good innings … Splendid send-off … Very moving service … Such beautiful flowers … You are so wonderfully brave, Lily.’

It’s not bravery: my squared shoulders, head held high, that careful expression of modesty and gratitude. Not bravery, just determination to survive today and, as soon as possible, get on with what remains of my life. The body in the expensive coffin, lined with Verners’ silk and decorated with lilies, and now deep in the ground, is not the man I’ve loved and shared my life with for the past fifty-five years.

It is not the man who helped to put me back together after the shattering events of the war, who held my hand and steadied my heart with his wise counsel, the man who took me as his own and became a loving father and grandfather. The joy of our lives together helped us both to bury the terrors of the past. No, that person disappeared months ago, when the illness took its final hold. His death was a blessed release and I have already done my grieving. Or at least, that’s what I keep telling myself.

After the service the house fills with people wanting to ‘pay their final respects’. But I long for them to go, and eventually they drift away, leaving behind the detritus of a remembered life along with the half-drunk glasses, the discarded morsels of food.

Around me, my son and his family are washing up, vacuuming, emptying the bins. In the harsh kitchen light I notice a shimmer of grey in Simon’s hair (the rest of it is dark, like his father’s) and realise with a jolt that he must be well into middle age. His wife Louise, once so slight, is rather rounder than before. No wonder, after two babies. They deserve to live in this house, I think, to have more room for their growing family. But today is not the right time to talk about moving.

I go to sit in the drawing room as they have bidden me, and watch for the first time the slide show that they have created for the guests at the wake. I am mesmerised as the TV screen flicks through familiar photographs, charting his life from sepia babyhood through monochrome middle years and into a technicolour old age, each image occupying the screen for just a few brief seconds before blurring into the next.

At first I turn away, finding it annoying, even insulting. What a travesty, I think, a long, loving life bottled into a slide show. But as the carousel goes back to the beginning and the photographs start to repeat themselves, my relief that he is gone and will suffer no more is replaced, for the first time since his death, by a dawning realisation of my own loss.

It’s no wonder I loved him so; such a good looking man, active and energetic. A man of unlimited selflessness, of many smiles and little guile. Who loved every part of me, infinitely. What a lucky woman. I find myself smiling back, with tears in my eyes.

My granddaughter brings a pot of tea. At seventeen, Emily is the oldest of her generation of Verners, a clever, sensitive girl growing up faster than I can bear. I see in her so much of myself at that age: not exactly pretty in the conventional way – her nose is slightly too long – but striking, with smooth cheeks and a creamy complexion that flushes at the slightest hint of discomfiture. Her hair, the colour of black coffee, grows thick and straight, and her dark inquisitive eyes shimmer with mischief or chill with disapproval. She has that determined Verner jawline that says, ‘don’t mess with me’. She’s tall and lanky, all arms and legs, rarely out of the patched jeans and charity-shop jumpers which seem to be all the rage with her generation these days. Unsophisticated but self-confident, exhaustingly energetic – and always fun. Had my own daughter lived, I sometimes think, she would have been like Emily.

At this afternoon’s wake the streak of crimson she’s emblazoned into the flick of her fringe was like an exotic bird darting among the dark suits and dresses. Soon she will fly, as they all do, these independent young women. But for the moment she indulges me with her company and conversation, and I cherish every moment.

She hands me a cup of weak tea with no milk, just how I like it, and then plonks herself down on the footstool next to me. We watch the slide show together for a few moments and she says, ‘I miss Grandpa, you know. Such an amazing man. He was so full of ideas and enthusiasm – I loved the way he supported everything we did, even the crazy things.’ She’s right, I think to myself. I was a lucky woman.

Читать дальше