4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This Ebook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © Owen Booth 2018

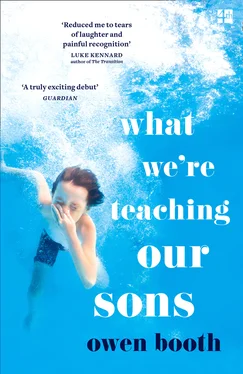

Cover design by Heike Schüssler

Cover photograph © Shutterstock

Owen Booth asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008282592

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008282608

Version: 2019-04-12

To Stan and Arthur

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Great Outdoors

Drowning

Heartbreak

Philosophy

Work

Whales

Grandfathers

Women

Money

Geology

Sport

Emotional Literacy

Sex

Plane Crashes

The Big Bang

Ex-Girlfriends

The Loneliness of Billionaires

Crying

Europe

Empathy

Haunted Houses

Relationships

Mountains

Drugs

The Bradford Goliath

Gambling

Food

The Life-Saving Properties of Books

Crime

Glaciers

What Happens When You Get Struck by Lightning

The World’s Most Dangerous Spiders

Friendship

Single Mothers

The Conquest of the South Pole

Monsters

Romance

Nostalgia

Practical Life Skills

Teenage Girls

The Abominable Snowman

Violence

Rites of Passage

Vikings

The Particular Smell of Hospitals at Three in the Morning

The War Against the Potato Beetle

Relativity

Pirates

Hotels

The Aftermath of Disasters

Drinking

The Pointlessness of Guilt

War

The Fifteen Foolproof Approaches to Making Someone Fall in Love with You

Life

The Wonderful Colours of the Non-Neurotypical Spectrum

Martians

The Ones that Got Away

Video Games

The Extinction of the Dinosaurs

Art

Women, Again

The Importance of Good Posture and Looking After your Teeth

Fatherhood

Death

Ghosts

The Ultimate Fate of the Universe

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

We’re teaching our sons about the great outdoors.

We’re teaching them how to appreciate the natural world, how to understand it, how to survive in it. As concerned fathers have apparently been teaching their sons since the Palaeolithic.

We’re teaching our sons how to make fires and lean-to shelters, how to tie twenty-five different kinds of knot, how to construct animal traps from branches and vines. We’re teaching them how to catch things, how to kill things, how to gut things. Out on the frozen marshes before dawn we produce hundreds of rabbits out of sacks, try to show our sons how to skin the rabbits.

Our sons look over our shoulders, distracted by the beautiful sunrise. They don’t want anything to do with skinning rabbits.

Out on the frozen marsh we explain the importance of being self-sufficient, and capable, and knowing the names of different cloud formations and geological features, and how to identify birds by their song.

‘Cumulonimbus,’ we say. ‘Cirrus. Altostratus. Terminal moraine. Blackbird. Thrush. Wagtail.’

We hand out fact sheets and pencils, collect the rabbits. We promise prizes to whoever can identify the most types of trees.

‘Can we set things on fire again?’ our sons ask.

The stiff grass creaks under our feet as we make our way back to the car park. The sky is the colour of rusted copper.

‘Can we set fire to a car?’

‘No, you can’t set fire to a car,’ we say. ‘Why would you want to set fire to a car?’

‘To see what would happen,’ our sons mutter, sticking their bottom lips out.

We look at our sons, half in fear, wondering what we have made.

We’re teaching our sons about drowning.

We tell them how we almost drowned when we were four years old. How we can still remember the feeling of being dragged along the bottom of the swollen river, the gravel in our faces, the smell of the hospital that lingered for weeks afterwards.

We don’t want this to happen to our sons. Or worse.

We take our sons swimming every Sunday morning, try to teach them how to stay afloat. Each week we have to find a new swimming pool, slightly further from where we live, slightly more overcrowded. The council is methodically demolishing all the sports centres in the borough as part of the Olympic dividend.

We are being concentrated into smaller and smaller spaces.

In the water our sons cling to us. Our hundreds of sons. They splash and kick their legs gamely, but they don’t seem to be getting any closer to being able to swim. We have to bribe them to put their faces under the water, and the price goes up every week.

We’re sure it wasn’t like this when we were children.

The water is a weird colour and tiles keep falling off the ceiling onto the swimmers’ heads. A scum of discarded polystyrene cups floats in the corner of the pool. It’s hotter than a sauna in here.

Also, we keep being distracted by the sight of the swimsuited mothers. The mothers who come in all sorts of fantastic shapes and sizes. They look as sleek as sea otters in their black swimsuits. They make us ashamed of our hairy backs, our formerly impressive chests, our pathetic tattoos.

We hope they can look at us with kinder eyes.

We crouch low in the water like middle-aged crocodiles, stealing glances at the sleek sea-otter mothers, and our sons put their arms around our necks and refuse to let go.

In the changing rooms we hold on to our sons’ tiny, fragile bodies; feel the terrible responsibility of lost socks, and impending colds, and the effects of chlorine on skin and lungs. We wrap our sons in towels, blow dry their hair, try not to consider the future and all the upcoming catastrophes that we can’t protect them from.

We promise ourselves that next week we’ll get it right.

We’re teaching our sons about heartbreak.

Its inevitability. Its survivability. Its necessity. That sort of thing.

We take our sons to meet the heartbroken men. We have to show our credentials at the gate. We have a letter of introduction.

Our jeeps bounce across the rolling scrubland under huge blackening skies. As we approach the compound a group of men in camouflage gear watch us carefully. They all have beer bellies and assault rifles.

The heartbroken men are heartbroken on account of the breakdown of their marriages, and the fact that they never see their children, and the fact that they’re earning less than they expected to be at this point in their lives, and the fact that no one takes them seriously any more. In their darkest moments the heartbroken men suspect that no one took them seriously before, either. The fathers of the heartbroken men loom large. Their hard-drinking, angry fathers. And their fathers and their fathers and their fathers before them.

Читать дальше