Hitler had offended against all these values and beliefs. He was an uncouth parvenu who lacked manners, education, culture and any of the attributes of refinement which army officers so valued in themselves. He demanded allegiance to himself, not the state. He first shamed and then sacked a head of the army (Fritsch), and used the opportunity to take personal command. He had led an assault on the values of decency, and unleashed his supporters and secret police to commit appalling violence against German citizens. Worst of all, he was marching Germany to a war which most senior military figures believed would end in defeat and disaster.

The problem for the generals, however, was that the army (known as the Reichswehr before the Fritsch crisis and the Heer afterwards *) was no longer the same organisation as the one in which they had grown up.

The army’s unwillingness to protest at the horrors of the Night of the Long Knives – even though one of its most senior brethren had been amongst the murdered – and its quiet acquiescence during Beck’s ‘blackest day’, when all the generals meekly lined up to take the oath of allegiance to Hitler, had weakened both its influence and its self-respect. The army’s leaders may have been trained to take bold decisions in battle, but their indecisiveness and hesitancy on the field of politics was – and would continue to be – a fatal brake on their ability to halt or change what all of them believed was a coming catastrophe. A British politician described the Wehrmacht leadership in 1938 as ‘a race of carnivorous sheep’. Even allowing for the fact that this was an easy criticism to make when you did not have to risk your life to oppose your government, there was much truth in the cruel epithet.

The composition of the Wehrmacht was also different from its predecessor. The old professional army, along with the traditional comradeship of its officer corps, had been diluted and submerged under the vast expansion of the army’s numbers. The flood of new equipment, much of it of world-beating quality, along with the attention, promotions, medals – and even in some cases money and estates – which Hitler showered on the Wehrmacht and its senior officers, sapped the army’s will to do what it knew it should to stop the headlong rush to war.

Nevertheless, pre-war opposition to Hitler remained strong amongst the most senior ranks of the Wehrmacht, even to the point of contemplating a coup to remove him. In 1938, those who supported Ludwig Beck’s view that if Hitler could not be stopped, he would have to be removed, included the commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht, General Walther von Brauchitsch, and the majority of his senior generals, especially in the Reserve Army †based around Berlin.

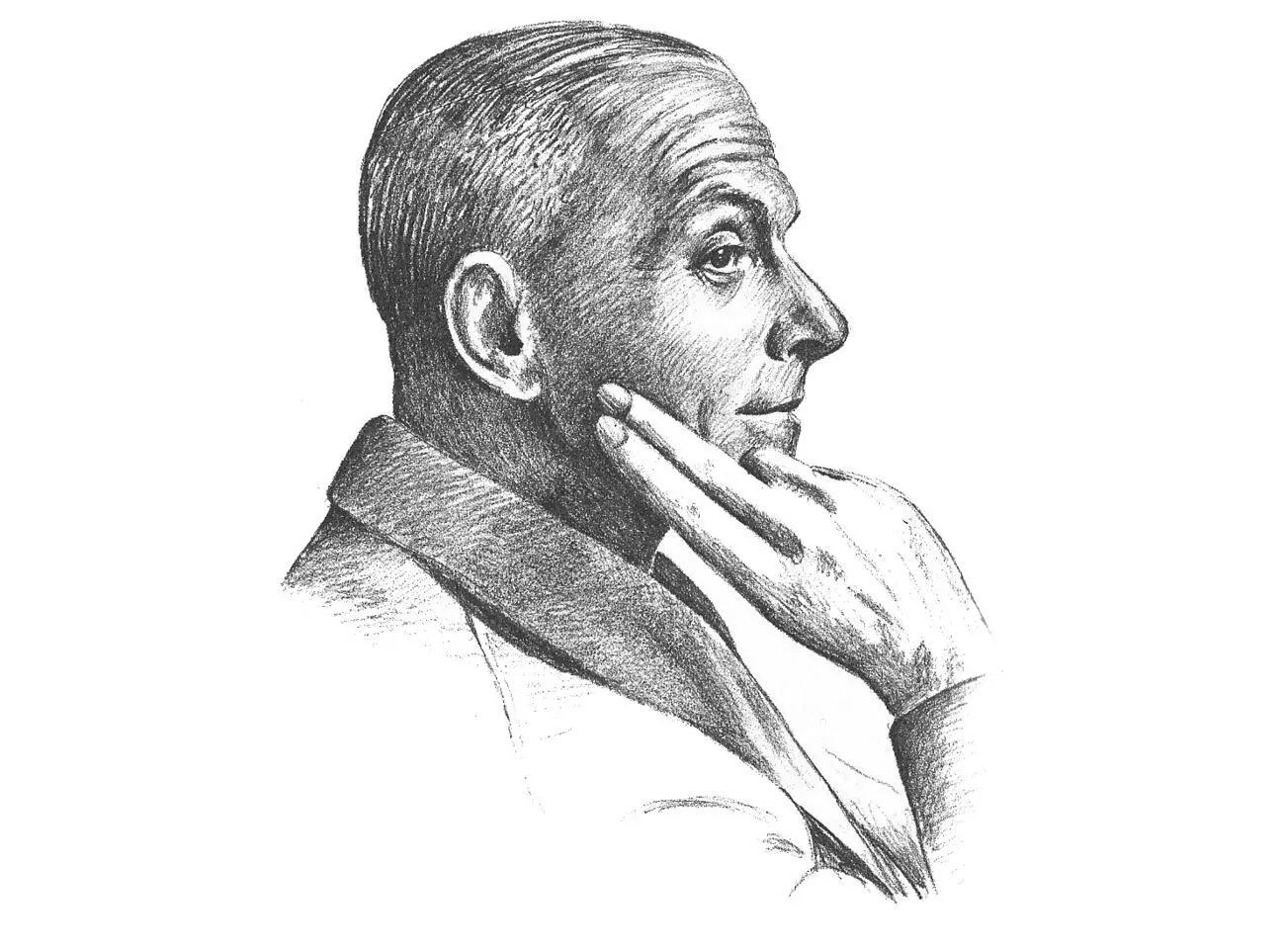

Although active resistance to Hitler was variably scattered across most German institutions, its highest concentration was in the Abwehr, and particularly in the Tirpitzufer building (nicknamed the Fuchsbau , or Fox’s Lair), which was part of a large Berlin administrative complex called the Bendlerblock. This also housed the Naval Warfare Command and the headquarters of both the Wehrmacht and the Reserve Army. Though physically connected to the Bendlerblock, the closed enclave of Abwehr headquarters was in every other way a world apart. Here Wilhelm Canaris gathered together as many as he could of those who, like him, opposed Hitler. They formed such a tight-knit group that the Tirpitzufer was sometimes referred to in Berlin circles as ‘Canaris Familie GmBH’ (The Canaris Clan Inc.). Among those closest to the Abwehr chief were Hans Bernd Gisevius, a lawyer of formidable physical proportions whom his friends christened the ‘eternal plotter’; Hans von Dohnányi, a gifted young judge who was the son of the famous composer Ernst von Dohnányi and brother-in-law of Dietrich Bonhoeffer; and the impetuous, fanatical Hitler hater and member of Pastor Niemöller’s congregation, Colonel Hans Oster. Sleek, fearless, cunning and a gifted amateur cello player, Oster, who made a habit of referring to Hitler as ‘the Swine’, was described by one contemporary as ‘an elegant cavalry officer of the old school, handsome, gallant with the ladies and contemptuous of the national socialist leaders. He was all for striking when the iron was hot; but the admiral had a more hesitant nature.’

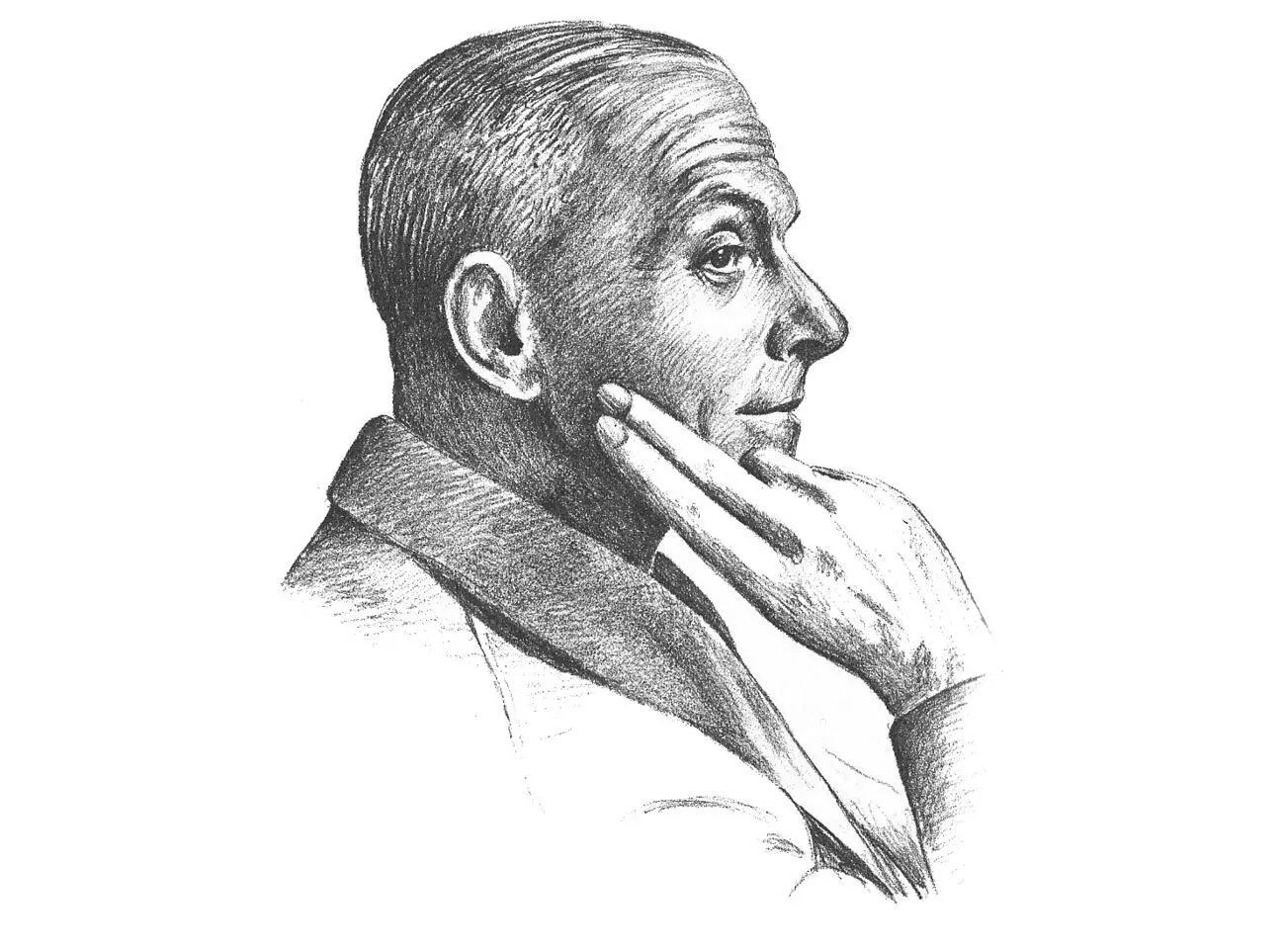

Hans Oster

Canaris encouraged his senior lieutenants to do as he did, and recruit those sympathetic to the cause. His often-repeated instruction when it came to new recruits was ‘Being anti-Nazi is more important than any other quality.’ He also went out of his way to use the Abwehr as a refuge for Jews, placing them in posts outside Germany beyond the reach of the Gestapo, and claiming when challenged that they were essential to the Abwehr’s work in gathering foreign intelligence.

In the middle of the 1930s, the Abwehr over which Canaris presided as what one colleague referred to as the ‘ grande éminence grise ’ was probably the best foreign-intelligence service in the world. The French Deuxième Bureau, one of the most proficient interwar spy services in Europe, went through a series of convulsive reorganisations in the early 1930s which sapped its effectiveness. Britain’s MI6 was going through a difficult period too, after much of its network of intelligence stations across the Continent had been blown. A whole new British spy network was being constructed in great secrecy, and without the knowledge of anyone apart from the MI6 chief Sir Hugh Sinclair and his closest advisers. This was known, rather melodramatically, as the ‘Z Organisation’, after its creator ‘Colonel Z’, otherwise known as Claude Edward Marjoribanks Dansey. The Russian spy agencies, meanwhile, though still capable of effective work, were hobbled by the repeated waves of Stalin’s purges.

Canaris’s value to Hitler lay in the priceless information he was able to bring his chief, including, crucially, both the military plans and the political intentions of his foreign enemies. Britain and France, with their many high-level admirers of Hitler and their public policies of appeasement, were rich sources of information for Canaris’s Abwehr. Before the war Canaris boasted to Juan March (or was it a threat, given March’s dealings with the British?): ‘I have penetrated the [British] Naval Intelligence Division and MI6. So if any German, however important or discreet, felt tempted to work with the British, be sure I should find out.’ According to his own claim, Canaris had one very high-level source close enough to the British cabinet to enable him to assure Hitler in early 1936 that if Germany marched into the Versailles-protected demilitarised zone of the Rhineland, Britain would not energetically oppose this.

The Abwehr chief himself set the tone of his organisation from his Spartan office on the third floor of the Tirpitzufer. At one end of a room of modest proportions was Canaris’s desk, behind which were three full-length windows and a glazed door leading onto a small balcony looking over the Landwehr Canal. The desk was unadorned except for a routine scatter of papers, a model of his old cruiser the Dresden , and a small paperweight in the shape of the three monkeys – ‘See no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil.’ Otherwise the room was largely empty save for two or three chairs, a bookshelf full of books, many of them on music and the arts, and an iron camp bed on which Canaris would from time to time take a nap. Only three photographs hung on his walls – one of Franco, one of a handsome young Hungarian hussar, and one of his beloved dachshund Seppl, which took pride of place on the wall immediately opposite his desk.

Читать дальше