Meteors

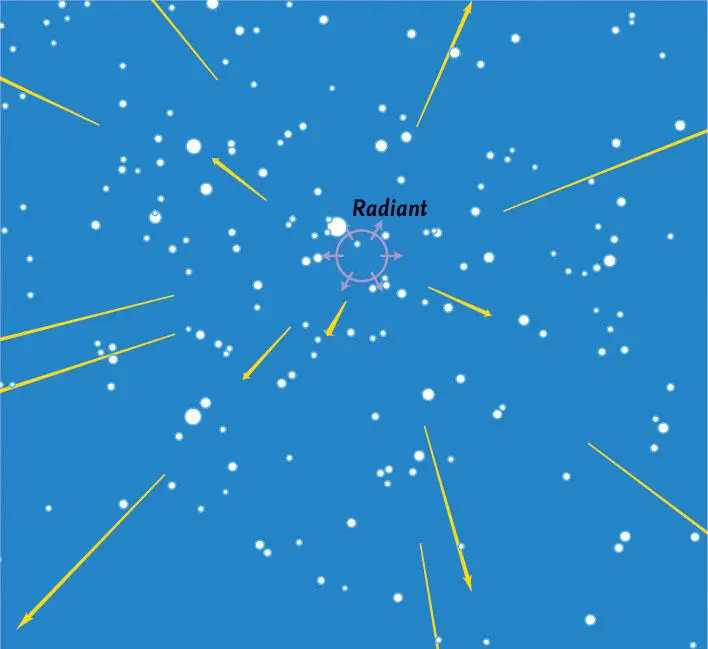

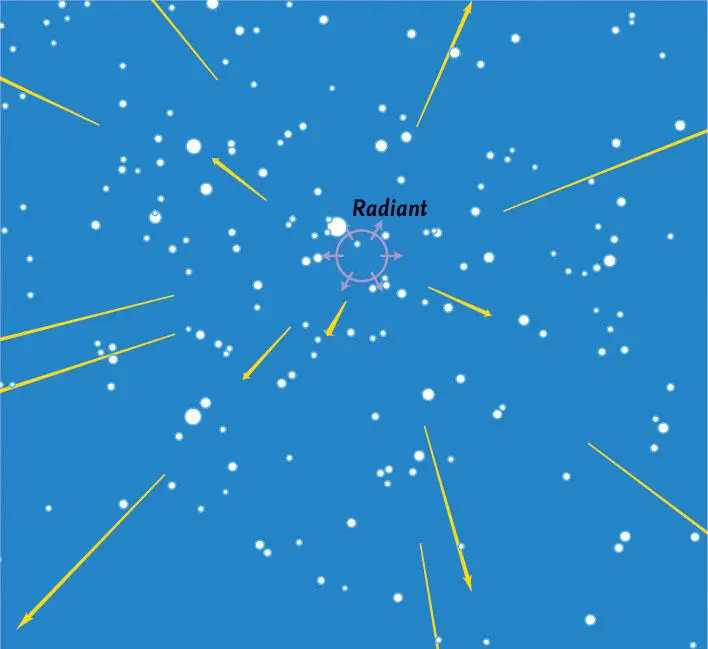

At some time or other, nearly everyone has seen a meteor– a ‘shooting star’ – as it flashed across the sky. The particles that cause meteors – known technically as ‘meteoroids’ – range in size from that of a grain of sand (or even smaller) to the size of a pea. On any night of the year there are occasional meteors, known as sporadics, that may travel in any direction. These occur at a rate that is normally between three and eight in an hour. Far more important, however, are meteor showers, which occur at fixed periods of the year, when the Earth encounters a trail of particles left behind by a comet or, very occasionally, by a minor planet (asteroid). Meteors always appear to diverge from a single point on the sky, known as the radiant, and the radiants of major showers are shown on the monthly charts. Meteors that come from a circular area 8° in diameter around the radiant are classed as belonging to the particular shower. All others that do not come from that area are sporadics (or occasionally from another shower that is active at the same time). A list of the major meteor showers is given here.

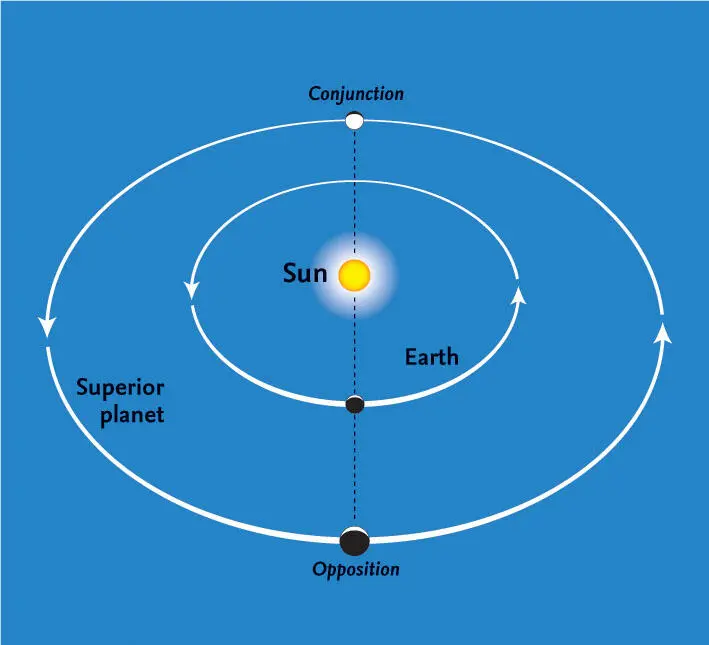

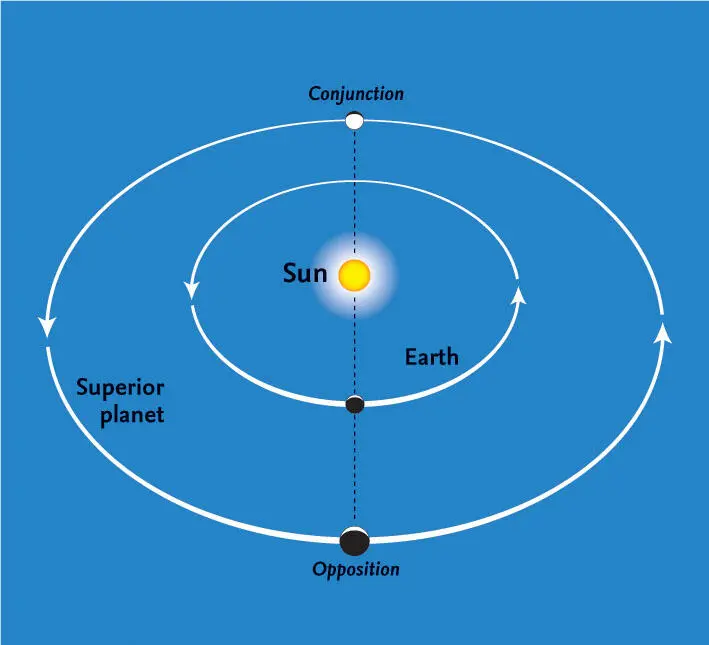

Superior planet.

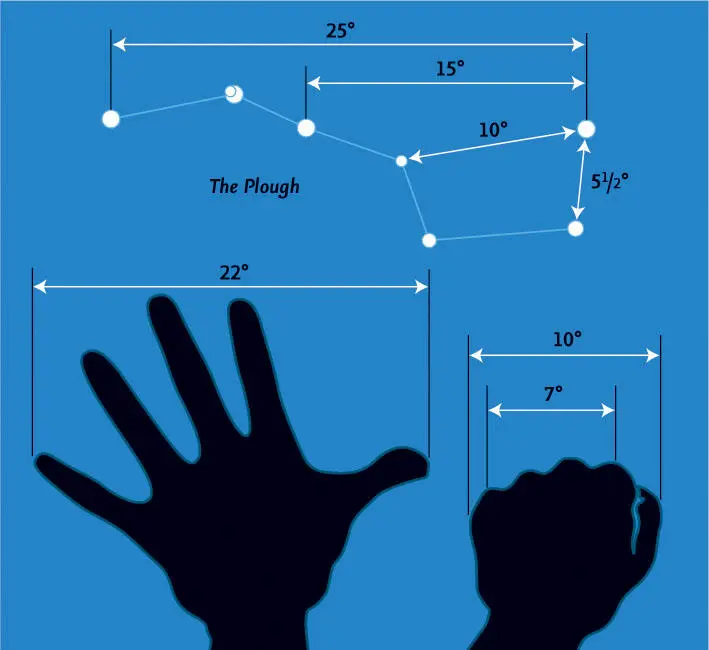

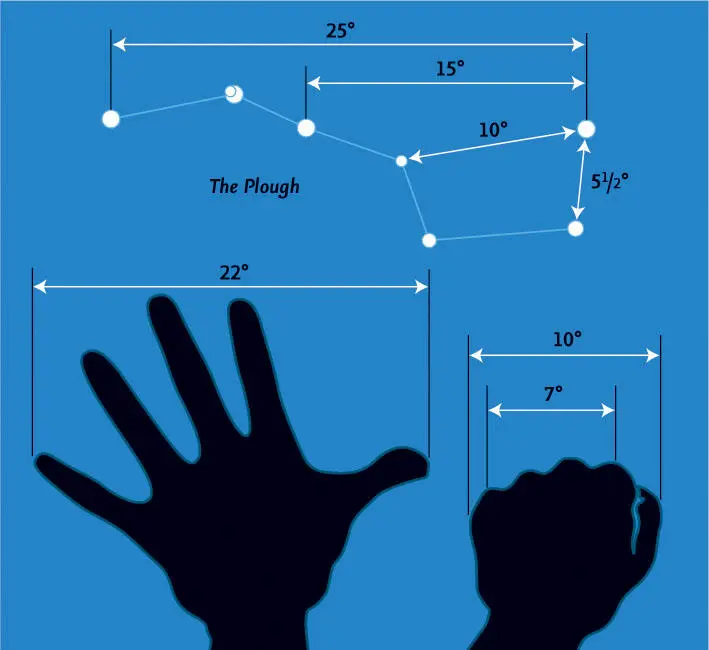

Although the positions of the various shower radiants are shown on the monthly charts, looking directly at the radiant is not the most effective way of seeing meteors. They are most likely to be noticed if one is looking about 40–45° away from the radiant position. (This is approximately two hand-spans as shown in the diagram for measuring angles.)

Other objects

Certain other objects may be seen with the naked eye under good conditions. Some were given names in antiquity – Praesepe is one example – but many are known by what are called ‘Messier numbers’, the numbers in a catalogue of nebulous objects compiled by Charles Messier in the late eighteenth century. Some, such as the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, and the Orion Nebula, M42, may be seen by the naked eye, but all those given in the list will benefit from the use of binoculars. Apart from galaxies, such as M31, which contain thousands of millions of stars, there are also two types of cluster: open clusters, such as M45, the Pleiades, which may consist of a few dozen to some hundreds of stars; and globular clusters, such as M13 in Hercules, which are spherical concentrations of many thousands of stars. One or two gaseous nebulae, consisting of gas illuminated by stars within them, are also visible. The Orion Nebula, M42, is one, and is illuminated by the group of four stars, known as the Trapezium, which may be seen within it by using a good pair of binoculars.

Meteor shower (showing the April Lyrid radiant).

Measuring angles in the sky.

Some interesting objects.

| Messier / NGC |

Name |

Type |

Constellation |

Maps (months) |

| — |

Hyades |

open cluster |

Taurus |

Sep. - Apr. |

| — |

Double Cluster |

open cluster |

Perseus |

All year |

| — |

Melotte 111 (Coma Cluster) |

open cluster |

Coma Berenices |

Jan. - Aug. |

| M3 |

— |

globular cluster |

Canes Venatici |

Jan. - Sep. |

| M4 |

— |

globular cluster |

Scorpius |

May - Aug. |

| M8 |

Lagoon Nebula |

gaseous nebula |

Sagittarius |

Jun. - Sep. |

| M11 |

Wild Duck Cluster |

open cluster |

Scutum |

May - Oct. |

| M13 |

Hercules Cluster |

globular cluster |

Hercules |

Feb. - Nov. |

| M15 |

— |

globular cluster |

Pegasus |

Jun. - Dec. |

| M22 |

— |

globular cluster |

Sagittarius |

Jun. - Sep. |

| M27 |

Dumbbell Nebula |

planetary nebula |

Vulpecula |

May - Dec. |

| M31 |

Andromeda Galaxy |

galaxy |

Andromeda |

All year |

| M35 |

— |

open cluster |

Gemini |

Oct. - May |

| M42 |

Orion Nebula |

gaseous nebula |

Orion |

Nov. - Mar. |

| M44 |

Praesepe |

open cluster |

Cancer |

Nov. - Jun. |

| M45 |

Pleiades |

open cluster |

Taurus |

Aug. - Apr. |

| M57 |

Ring Nebula |

planetary nebula |

Lyra |

Apr. - Dec. |

| M67 |

— |

open cluster |

Cancer |

Dec. - May |

| NGC 752 |

— |

open cluster |

Andromeda |

Jul. - Mar. |

| NGC 3242 |

Ghost of Jupiter |

planetary nebula |

Hydra |

Feb. - May |

The Northern Circumpolar Constellations

The northern circumpolar stars are the key to starting to identify the constellations. For anyone in the northern hemisphere they are visible at any time of the year, and nearly everyone is familiar with the seven stars of the Plough – known as the Big Dipper in North America – an asterism that forms part of the large constellation of Ursa Major(the Great Bear).

Ursa Major

Because of the movement of the stars caused by the passage of the seasons, Ursa Major lies in different parts of the evening sky at different periods of the year. The diagram below shows its position for the four main seasons. The seven stars of the Plough remain visible throughout the year anywhere north of latitude 40°N. Even at the latitude (50°N) for which the charts in this book are drawn, many of the stars in the southern portion of the constellation of Ursa Major are hidden below the horizon for part of the year or (particularly in late summer) cannot be seen late in the night.

Polaris and Ursa Minor

The two stars Dubheand Merak(α and β Ursae Majoris, respectively), farthest from the ‘tail’ are known as the ‘Pointers’. A line from Merak to Dubhe, extended about five times their separation, leads to the Pole Star, Polaris, or α Ursae Minoris. All the stars in the northern sky appear to rotate around it. There are five main stars in the constellation of Ursa Minor, and the two farthest from the Pole, Kochaband Pherkad(β and γ Ursae Minoris, respectively), are known as ‘The Guards’.

Читать дальше