Troy came along at a time when thoroughly nice girls were often called Dulcie, Edith, Cecily, Mona, Madeleine. Even, alas, Gladys. I wanted her to have a plain, rather down-to-earth first name and thought of Agatha – not because of Christie – and a rather odd surname that went well with it, so she became Agatha Troy and always signed her pictures ‘Troy’ and was so addressed by everyone. Death in a White Tie might have been called Siege of Troy .

Her painting is far from academic but not always non-figurative. One of its most distinguished characteristics is a very subtle sense of movement brought about by the interrelationships of form and line. Her greatest regret is that she never painted the portrait of Isabella Sommita, which was commissioned in the book I am at present writing. The diva was to have been portrayed with her mouth wide open, letting fly with her celebrated A above high C. It is questionable whether she would have been pleased with the result. It would have been called Top Note .

Troy and Alleyn suit each other. Neither impinges upon the other’s work without being asked, with the result that in Troy’s case she does ask pretty often, sometimes gets argumentative and uptight over the answer and almost always ends up by following the suggestion. She misses Alleyn very much when they are separated. This is often the case, given the nature of their work, and on such occasions each feels incomplete and they write to each other like lovers.

Perhaps it is advisable, on grounds of credibility, not to make too much of the number of times coincidence mixes Troy up in her husband’s cases: a situation that he embraces with mixed feelings. She is a reticent character and as sensitive as a sea urchin, but she learns to assume and even feel a certain detachment.

‘After all,’ she has said to herself, ‘I married him and I would be a very boring wife if I spent half my time wincing and showing sensitive.’

I like Troy. When I am writing about her, I can see her with her shortish dark hair, thin face and hands. She’s absentminded, shy and funny, and she can paint like nobody’s business. I’m always glad when other people like her, too.

Death in Ecstasy

DEATH IN ECSTASY

For the family in Kent

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

The Characters in the Case

Foreword

PART ONE

1 Entrance to a Cul-de-sac

2 The House of the Sacred Flame

3 Death of an Ecstatic Spinster

4 The Yard

5 A Priest and Two Acolytes

6 Mrs Candour and Mr Ogden

7 Janey and Maurice

8 The Temperament of M. de Ravigne

9 Miss Wade

10 A Piece of Paper and a Bottle

11 Contents of a Desk, a Safe, and a Bookcase

12 Alleyn Takes Stock

PART TWO

13 Nannie

14 Nigel Takes Stock

15 Father Garnette Explores the Contents of a Mare’s Nest

16 Mr Ogden Puts his Trust in Policemen

17 Mr Ogden Grows Less Trustful

18 Contribution from Miss Wade

19 Alleyn Looks for a Flat

20 Fools Step In

21 Janey Breaks a Promise

22 Sidelight on Mrs Candour

23 Mr Ogden at Home

24 Maurice Speaks

25 Alleyn Snuffs the Flame

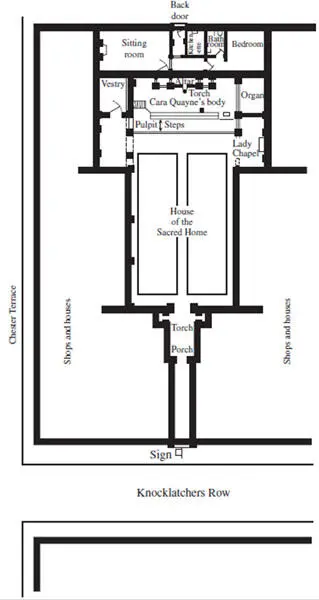

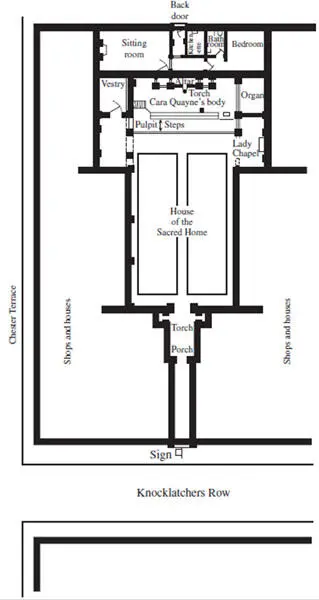

In case the House of the Sacred Flame might be thought to bear a superficial resemblance to any existing church or institution, I hasten to say that if any similarity exists it is purely fortuitous. The House of the Sacred Flame, its officials, and its congregation are all imaginative and exist only in Knocklatchers Row. None, as far as I am aware, has any prototype in any part of the world.

My grateful thanks are due to Robin Page for his advice in the matter of sodium cyanide; to Guy Cotterill for the plan of the House of the Sacred Flame, and to Robin Adamson for his fiendish ingenuity in the matter of home-brewed poisons.

NGAIO MARSH

Christchurch, New Zealand

Part One

CHAPTER 1 Entrance to a Cul-de-sac

On a pouring wet Sunday night in December of last year a special meeting was held at the House of the Sacred Flame in Knocklatchers Row.

There are many strange places of worship in London, and many remarkable sects. The blank face of a Cockney Sunday masks a kind of activity, intermittent but intense. All sorts of queer little religions squeak, like mice in the wainscoting, behind its tedious façade.

Perhaps these devotional side-shows satisfy in some measure the need for colour, self-expression and excitement in the otherwise drab lives of their devotees. They may supply a mild substitute for the orgies of a more robust age. No other explanation quite accounts for the extraordinary assortment of persons that may be found in their congregations.

Why, for instance, should old Miss Wade beat her way down the King’s Road against a vicious lash of rain and in the teeth of a gale that set the shop signs creaking and threatened to drive her umbrella back into her face? She would have been better off in her bed-sitting-room with a gas-fire and her library book.

Why had Mr Samuel J. Ogden dressed himself in uncomfortable clothes and left his apartment in York Square for the smelly discomfort of a taxi and the prospect of two hours without a cigar?

What induced Cara Quayne to exchange the amenities of her little house in Shepherd Market for a dismal perspective of wet pavements and a deserted Piccadilly?

What more insistent pleasure drew M. de Ravigne away from his Van Goghs, and the satisfying austerity of his flat in Lowndes Square?

If this question had been put to these persons, each of them, in his or her fashion, would have answered untruthfully. All of them would have suggested that they went to the House of the Sacred Flame because it was the right thing to do. M. de Ravigne would not have replied that he went because he was madly in love with Cara Quayne; Cara Quayne would not have admitted that she found in the services an outlet for an intolerable urge towards exhibitionism. Miss Wade would have died rather than confess that she worshipped, not God, but the Reverend Jasper Garnette. As for Mr Ogden, he would have broken out immediately into a long discourse in which the words ‘uplift,’ ‘renooal,’ and ‘spiritual regeneration’ would have sounded again and again, for Mr Ogden was so like an American as to be quite fabulous.

Cara Quayne’s car, Mr Ogden’s taxi, and Miss Wade’s goloshes all turned into Knocklatchers Row at about the same time.

Knocklatchers Row is a cul-de-sac leading off Chester Terrace and not far from Graham Street. Like Graham Street it is distinguished by its church. In December of last year the House of the Sacred Flame was obscure. Only members of the congregation and a few of their friends knew of its existence. Chief Detective-Inspector Alleyn had never heard of it. Nigel Bathgate, looking disconsolately out of his window in Chester Terrace, noticed its sign for the first time. It was a small hanging sign made of red glass and shaped to represent a flame rising from a cup. Its facets caught the light as a gust of wind blew the sign back. Nigel saw the red gleam and at the same time noticed Miss Wade hurry into the doorway. Then Miss Quayne’s car and Mr Ogden’s taxi drew up and the occupants got out. Three more figures with bent heads and shining mackintoshes turned into Knocklatchers Row. Nigel was bored. He had the exasperated curiosity of a journalist. On a sudden impulse he seized his hat and umbrella, ran downstairs and out into the rain. At that moment Detective-Inspector Alleyn in his flat in St James’s looked up from his book and remarked to his servant: ‘It’s blowing a gale out there. I shall be staying in tonight.’

Читать дальше