“Herr Colonel,” I stuttered. “I doubt that... I mean, Sir... I think that I might be more a danger to your venture than an asset...”

“Nonsense!” Himmel boomed, and it was then that I understood his view of the world, the war, and the rites of passage. He was offering me an honor which could not be declined. “I do not expect you to contribute anything worthwhile, Shtefan, but I do expect you to keep yourself intact. And this as well...”

He reached into the footlocker and brought out a small leather case, slapping it into my palm.

“It is a Leica and two extra rolls of film. Take photos, and stay close behind me.”

I must have been regarding him with the same expression of a child who first witnesses his parents’ fornication. He actually grinned at me.

“British commandos have captured a staff officer of the 1st Panzer. We are going to free him. Just before dawn. Get yourself a helmet.”

With that, he strode from the room, shouting orders to Captain Friedrich. With a trembling hand, I managed to slide the pistol into my holster and snap it shut, and as instructed, I slipped the extra magazine into my trouser pocket. Then, for a moment, I considered running straight for my chamber and the servants’ entrance and not stopping until I had swum the Rhine and walked all the way to France. Unfortunately, we still occupied all that part of Europe, and what might befall me in the embrace of some other Nazi officer could make this impending fate seem attractive by comparison.

There was an open bottle of wine on the commander’s desk. I drank a quarter of it quickly, and followed after him...

* * *

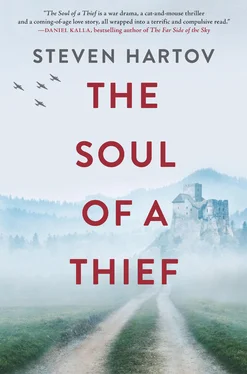

The castle was nestled upon a small soft meadow, in the cleavage of a pair of high peaks, and we wound away from it in utter darkness. The company cook’s fires danced dimly from a lower window, and I never had thought to regard that cold, bleak stone edifice as a home from which to regret departure.

I sat stiffly in the rear of Colonel Himmel’s staff car. The winter months were still fresh memories, and a harsh chill made the black air brittle, yet the Kübelwagen’s folding roof was not deployed, and I had to set my jaw against my chattering teeth. Behind us, two medium troop trucks with canvas roofs followed close, and despite the rutted road and trundling engines, I could hear the raiding complement of twenty-one men chattering and laughing from within. I had no doubt that I was the object of their mirth, for they had passed me by en route to debarkation, as I stood behind the Colonel clutching the camera and his map case. I no doubt served up the image of a martial jester, wearing a coal scuttle helmet too large for even an average man. Its rim fell well below my earlobes, and the commandos, sporting leopard camouflage smocks, hauling their machine pistols and light machine guns and even an anti-armor Panzerfaust, had unabashedly jerked their thumbs at me and howled as they boarded their trucks.

Himmel’s driver, an older, mustached corporal named Edward, deftly maneuvered the car along the winding mountain roads, without benefit of headlights. Beside him the Colonel sat, erect and silent, puffing a short cigar whose smoke wafted directly back into my face. Himmel was not wearing a helmet, but only a Feldmütze, the SS field cap angled smartly over his bristle of gray-blond hair, and every other member of the troop was similarly cavalier. But I was grateful for my steel hat, and certainly unconcerned with being out of fashion.

After two hours of a spine-numbing drive to the south, we rose from between the copses of mountainside trees and onto a higher road bordered by gently waving grass. A sliver of moon then peaked a distant crest, and Himmel turned his head to stare at it in disgust, as if his expression might convince the orb to retreat. Yet it only rose higher, throwing some small farmhouses and cattle fences into sharp relief. Soon, we were traversing a large flat meadow, and I realized we had climbed upon a lip overlooking the winding silver waters of the Rhine so far below. On any other night, in any other life, I would have noted the beauty of such a stunning vision. Yet something else caught my attention.

Sitting at the very top of the meadow were three large forms, silhouettes the likes of which I had never seen. They appeared to be enormous iron wasps, with faces of curving glass, ugly fat tires for feet, and above, double umbrellas of long glinting sword blades. I leaned forward in my seat, my mouth certainly agape, and Himmel turned his face to me and grinned.

“Hubschrauber,” he yelled above the car’s engine roar. “Helicopters. Have you never seen one?”

I believe that I slowly shook my head in disbelief. I had, of course, heard that someday there would be such an airplane, one that could lift straight up into the sky without benefit of wings. But as yet, I was certain that such things existed only in the ancient notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci.

“Skorzeny prefers a Storch,” Himmel continued. He meant the light aircraft favored by the infamous commando leader, Colonel Otto Skorzeny. “Scarface Skorzeny,” as he was often called, was a personal favorite of Hitler and clearly a competitor for Himmel’s glories. “But I managed to elicit these from the Luftwaffe. They’re Dragons, experimental.”

I did not know why Himmel seemed to be informing, or rather, confiding in me. Perhaps he expected me to someday write his memoirs? I had not long to consider this, as the staff car raced toward the first of the iron monsters. There are historians who swear that no such functional machines existed until years later, but I bear witness to the contrary. A low-pitched whine began to emanate from its massive engines, and its drooping blades began to slowly twirl. From that moment on, I was gripped by an icy fist of fear that set me to a sort of paralysis. The staff car slammed to a halt, and I sat in the back, staring and immobilized.

“Raus!” Himmel snatched at my tunic shoulder and fairly dragged me from the vehicle. I slipped and fell into the mud, and then he was pulling me along as he shouted orders to his men and to the pilots. I vaguely recall the trundle of many boots as the raiding complement ran and leaped into their respective helicopters, while Himmel pushed me to the wide open doorway of the first machine and kneed my buttocks as if I were a cow. I climbed in clumsily, already hyperventilating, gripping the Leica case as if it might save my life. Himmel stepped directly over my quivering form and squatted in the iron cavern just behind the pair of Luftwaffe pilots, and immediately the space was filled with the first seven SS of his forward element. They jockeyed for positions, falling hard on their rumps and tucking up their legs. Someone’s binoculars swung and struck my helmet with a resounding ping, and I saw Himmel twirling his finger in the air between the pilots and I felt my stomach leap for my throat as the horrible device left earth for heaven.

I do not know how long we flew, yet it certainly seemed forever. And I did not see very much, as for most of the journey my eyes were clamped shut. The engines roared like a carpenter’s lathe and a freezing wind sliced through the rattling compartment, and I remembered as a child being forced by my father to ride the great carnival wheel in Vienna’s Prater, and how I had peed in my trousers, an urge I barely contained at this moment. At one point, long into the horrible flight, someone slapped the top of my helmet, and I opened my eyes to see the grinning face of Captain Friedrich, his steel blue eyes merry and his flaxen eyebrows arched in utter thrill. He suddenly pinched my cheek with what one might suppose a gesture of comradely affection, yet it hurt so much I nearly yelled. But it was then I looked to the fuselage’s windows, and realized we were in fact skimming at breakneck speed through a deep and winding valley, and we were well below the peaks of its sides. I groaned and squeezed my eyes shut once more, and it required every muscle of my stomach not to regurgitate its contents.

Читать дальше